Guidance for students

Placement Pointers

- Arrange a meeting with your Academic Tutor and the Disability Advisory Service to discuss potential challenges and the support available prior to each placement.

- Discuss ways of working and what you have found most supportive in the past with your work-based placement mentor.

- Be prepared to ask for help and adapt support strategies if things are not working.

Orientation

Orientating new places and systems can sometimes be challenging for students with dyslexia. They need time to map out and explore new working environments.

- Plan the journey to school and practice it prior to each placement.

- Draw out seating plans for the classrooms/spaces in which you will work.

- Note specific points of orientation to help navigate your way around the school building, e.g., distinctive features such as water fountains or posters.

- Spend time orientating systems used by the school, e.g., databases/software such as CPOMS (Child Protection Online Monitoring System).

- Ask for support configuring your devices with the school’s.

Organisation and time management

Organisation and effective time management can pose significant challenges for some students with dyslexia. Supporting the development of organisational skills, both physically and cognitively can help with everyday working memory challenges and particularly with information processing.

Before each placement

- Establish a routine for the beginning and end of the day, e.g., packing your work bag the night before

- Set up physical and/or electronic folders prior to each placement

- Display a calendar overview of the placement timeframe with important dates and task deadlines clearly visible – seeing the bigger picture will help you manage your time more effectively and plan ahead

During each placement

- Identify tasks which will take longer to complete and block additional time for these, e.g., planning lessons for a new subject area

- Schedule time to complete administrative tasks – this can be during the periods when you have less energy

- Have a ‘to do when stressed’ list, e.g., tidying your desk area or putting up a display, so you are productive whilst giving your brain a chance to reset also

- Identify the times in the day when you feel most productive and map out the tasks you will complete during these times

- Develop a daily and weekly checklist system in your preferred format so no task is missed – use visual cues and colour association to differentiate between tasks

- Place tasks in chronological and priority order, setting yourself electronic reminders

- Prioritise tasks so important/time-sensitive ones are completed first

- Physically cross tasks off your ‘to do’ list so you can see when things have been completed

- Set individual deadlines in advance of an actual deadline to ensure important tasks are completed on time

- Set time limits for completing certain tasks so no time is wasted

- Have a clock visible in the classroom to support with time management during lessons

Reading

The difficulties a student with dyslexia may have when being presented with written material need to be taken into consideration. Review the sequence of the material, its format, accessibility of the font, line/word spacing and the contrast between text and background. Always use clear and concise language avoiding jargon, technical terms, figures of speech, idioms, and abbreviations.

Read the British Dyslexia Association’s Dyslexia friendly style guide for a set of principles to follow.

- Allow additional time for reading tasks, e.g., reading course documentation or school policies

- Use a coloured overlay or ask for materials to be printed or digitally displayed on laptops or Whiteboards using an appropriate coloured background (if Irlen syndrome is part of your dyslexia, this may be needed)

- Organise handbooks and course documentation into a format which supports your language processing, e.g., break paragraphs into bullet points and reformat tables if necessary

- Use text-to-speech software, e.g., MS Immersive Reader, when reading and digesting lengthy documentation

- When reading aloud in class, practice with smaller groups at first

- Practice reading texts before reading aloud and ensure you know the definition of unfamiliar vocabulary

- Take your time when reading aloud and draw on those pupils who are comfortable to read texts in front of their peers

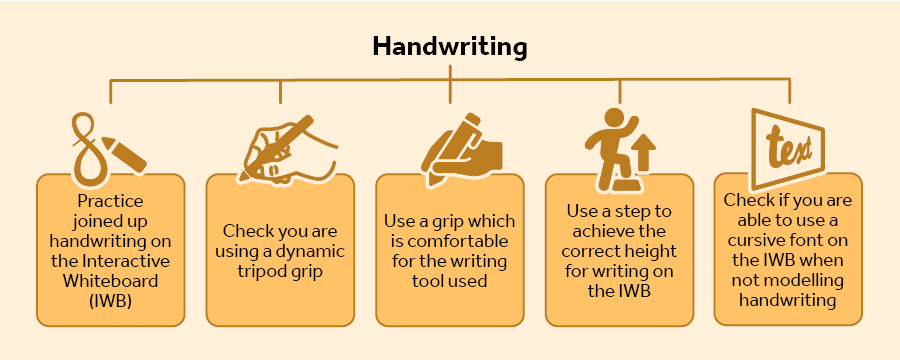

Spelling, writing and handwriting

Phonological awareness is the ability to hear and discriminate between phonemes in spoken words and code information for temporary storage. This type of phonological processing and visual recall can sometimes present a challenge for students when modelling spelling and writing in the classroom. A multisensory approach is often most supportive for students when meeting associated challenges of ‘live’ spelling and writing. The physical and mental effort of handwriting and sequencing letters correctly can be very tiring.

- Develop personally meaningful mnemonics for remembering spellings which are more challenging to commit to long-term memory

- Draw on previous, successful, ways you have used to learn unfamiliar spellings. This may include: syllable count, rhyme families, colour-coding words which are not decodable phonetically, drawing a picture association, using flashcards or the Look-Say-Cover-Write-Check method for more complex words, e.g: look say cover write check

photosynthesis[Look-Say-Cover-Write-Check method]

- Use Assistive Technology where possible, e.g., Office 365 dictate, spell check, predictive text, speech-to-text/text-to-speech software (for proofreading and editing what you have written)

- Pre-plan as much written work as possible to ease the cognitive load when live-modelling writing across different subject areas

- Underline/bold/colour-code subject specific or more challenging vocabulary within lesson plans so they are easier to identify and transfer to the Interactive Whiteboard

- Practice more challenging words in and out of context before delivery of the lesson

- Use a laptop or electronic spell checker in the classroom when appropriate

- Use a spell checker in the context of a sentence to ensure accuracy, e.g., ‘effect’ and ‘affect’ are easily confused

- Pause after writing a word you are uncertain of and take a moment to consider if it looks correct

- Annotate words with the pupils which may not be correct when live modelling writing, revisiting words to check spelling to ensure the flow of writing is not stilted

- Encourage pupils to develop independent strategies for spelling unfamiliar words, e.g., electronic dictionaries, word banks and glossaries

- Provide oral feedback rather than written feedback when appropriate

- Allocate additional time for important outward-facing written tasks such as communications with families

Working memory

Some students with dyslexia experience greater challenges with embedding language knowledge into their long-term memory for permanent storage. They often have difficulty in holding speech sounds in their working memory long enough to make use of them, practise them and retain for future use. Learning how to discard redundant or irrelevant information is a way in which students can avoid cognitive overload.

- Use name and word pronunciation apps to support verbal memory

- Write pupils’ and colleagues’ names phonetically, as a memo to yourself, of the correct pronunciation

- Address pupils by their name as frequently as possible to strengthen verbal memory and aid recall

- Record any questions you have as they arise rather than waiting until the end of the day so they are not forgotten or remembered out of context

- Keep a notepad handy to capture things you are told and wish to revisit at a later date

- Devise your own abbreviation system for note taking so information given verbally is easier to capture

- Ask permission to record meetings so you can revisit what was discussed

- Watch videos to help embed signs if using British Sign Language or Makaton in the classroom

- Display key words in a prominent place when teaching lessons which require recall of subject-specific terminology at a fast pace. This will support word finding so the pace of the lesson is not impacted

- Have written models of texts ready to share and ready for annotation to eliminate unnecessary copying or transferring from page to screen

- Practice lesson delivery prior to teaching, e.g., reading aloud and stepped explanations for multistep tasks

Information processing and sequencing

Sequencing and processing large amounts of verbal and written information can prove difficult for some students. The documentation associated with Initial Teacher Training and education in general is immense. In addition, planning appropriate sequences of teaching to impact learning on a daily basis can be extremely challenging at first.

Policies and procedures

- Change all documentation so it is displayed in your preferred format, e.g., font/colour/printed

- Seek quiet time out of the classroom towards the beginning of a placement for processing policies and procedures

- Make time to discuss school policies with a colleague, highlighting the parts which need to be recalled in practice, e.g., behaviour policy steps

- Use Post-it notes in longer documents to locate specific information or use a ‘Sticky Note’ app for electronic bookmarking

- Observe policies in action, i.e., the behaviour policy being implemented by other members of staff will support your understanding and recall

- Seek verbal as well as written explanations of how to implement policies

- Break the reading of policies down into more manageable parts – avoid reading all school policies in one go

- Read longer documents in short bursts, summarising the main points for each section as you go

- Record procedures step by step especially if you have been given the information verbally

- Use Post-it notes to break information down, reorder and build back up – use this strategy for lesson planning if useful also

Lesson planning

- Look at the whole unit of work so you understand where your teaching sits in the medium term and where the learning is going

- When lesson planning, start from the end point – what is the intended outcome?

- Mind map before lesson planning so you can visualise the big picture and see where the learning is going – link key words and images/visuals to help you remember key points and embed them

- Handwrite or word process lesson plans depending on preference

- Develop or follow a checklist/prompt sheet when going through the lesson planning process so all elements are included

- Talk through lessons with your mentor to verbalise the teaching sequence and review content

- Produce slides in your preferred format (in keeping with school policy) – print them out as a memory aid

- Use a format and structure for planning that suits your processing needs, e.g., step by step, chronological, tabular

- Plan the lessons you feel less confident with in more detail

- Orally rehearse key learning points

- Physically rehearse your lessons, especially those you are feeling less confident with (model it to yourself, your mentor or a friend)

- Ask pupils to explain their understanding of independent tasks so you can check your explanations have been clear

Managing fatigue and supporting concentration for students

It is important to recognise it may take longer to complete tasks which may lead to greater levels of fatigue. Consider the following points to reduce fatigue and increase levels of concentration:

Whenever possible, schedule regular breaks in between episodes of teaching to combat fatigue throughout the day

Plan short breaks when transitioning between tasks giving you time to reflect and refocus

Identify a quiet working space where you can eliminate distraction during the school day

When involved in planning and preparation time, use an adult fidget toy to aid concentration

If possible, take a short break at the end of the school day to rest and refocus

Tackle important and time-sensitive tasks first such as the adaptation of lesson plans for the following day

Plan plenty of screen breaks when working on a computer or device

Feedback

If you have any feedback regarding this guide, please contact Alison Silby: a.silby@reading.ac.uk or Stephanie Sharp: s.sharp@reading.ac.uk

Dyslexia guidance Guidance for mentors