Moving Assessment Online

There is an expectation that assessment practices should wherever possible follow existing MDFs. Assessment may be adapted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic where there is a valid pedagogical reason for doing so and where the current situation does not allow for the existing approach. For example, written assignments which can be submitted and uploaded via Blackboard in the usual way should not be changed, but unseen timed in-class tests that would normally have been conducted at a specific time and place under test conditions may require an alternative approach. Changes to assessment which do not impact on the MDF should be considered first. Please refrain from introducing participation or engagement marks unless this is already specified in the module description form (as outlined in Section 5.5 of the Assessment Handbook).

For 2020/21 all coursework should be submitted online, except in a small number of cases where online submission is technically not possible or is not consistent with the fair assessment of the work.

Guidance on how to convert physically submitted assignments or in-class tests to online submission

Whether adaptations to assessment are made or not, you are encouraged to consider designing in additional opportunities for student-student or student-tutor interactivity in order to provide students with opportunities for meaningful social interaction and foster their sense of belonging to a learning community.

Designing opportunities for student-student or student-tutor interactivity

In modules which involve group assessment, students will naturally engage in social interaction about their learning as they organise themselves, work collaboratively and co-construct their assessed work. Where students are individually assessed, they can also be provided with meaningful opportunities to engage in social interaction in scheduled interactive sessions and asynchronous peer-to-peer activities.

Interpreting assignment briefs

For example, when sharing assignment briefs with students, you can provide students with opportunities to interpret the brief in pairs and/or small groups and encourage them to ask questions and seek clarifications. Using synchronous tools for the groupwork aspect and asynchronous tools such as discussion boards to field the questions and provide answers is an excellent combination of approaches that results in a co-created assessment-related FAQs area that all can share.

Developing familiarity with assessment formats

Further useful opportunities for interaction can be used when students are dealing with unfamiliar assessment types. As part of their preparation for the assignment, you can provide opportunities for students to work in pairs or small groups to analyse and evaluate exemplars of the type in order to develop their understanding of its underlying structure, linguistic features and stylistic conventions with which to inform their own work.

A useful list of approaches to designing synchronous and asynchronous learning activities, some of which may also usefully be applied to assessment-related work can be found in Designing Learning Activities - Introduction.

Providing opportunities for collaborative formative assessment

Peer-to-peer activities can be an excellent form of formative assessment, providing students with opportunities to work together to negotiate their understanding of assessment requirements, gain insights into their own strengths and weaknesses and develop their assessment literacy overall.

Some suggestions are made below, but you are advised to consider the range of possibilities available in the online context. A list of activities that may provide opportunities for formative assessment can be found here: Designing learning activities – introduction.

Engaging with other students’ work

A common approach involves students working in pairs to assess and comment on work from previous cohorts using the same assessment criteria that will be used to assess them. This can take place synchronously or asynchronously, or in approaches that combine both. For instance, students might collaborate synchronously to assess the examples and then share their results and comments asynchronously for further asynchronous discussion and comment. Activities of this kind have been shown to develop students’ understanding and internalisation of assessment criteria, which they can then be applied to their own work.

Students can also use this kind of activity to engage with each other’s drafts, providing them with opportunities for useful formative feedback as well as developing their abilities to assess themselves. It may be useful to remind students of the differences between collaboration and collusion when undertaking this kind of activity.

Adapting assessments

Assessment may be adapted as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic where there is a valid pedagogical reason for doing so and where the current situation does not allow for the existing approach. In such cases, you will need to seek the necessary approval.

There are a range of assessment types that lend themselves well to the online context. A list of suggestions is provided here: Online alternatives to assessment tasks

The Academic Development and Enhancement team in CQSD will be happy to advise if you wish to discuss adapting your assessment: cqsd-ade@reading.ac.uk

Ensure learning outcomes and assessment are aligned

You should always begin with a consideration of how any revisions to assessment practices will provide students with the opportunity to evidence their achievement of the module learning outcomes.

The principle of constructive alignment, in which learning outcomes, teaching and assessment methods are inter-related and aligned is central to quality assurance and curriculum development practices in the UK higher education sector. Any adaptations to assessment must still align with the assessable learning outcomes of the module.

Inclusivity

No students should be disadvantaged because of adaptations made to assessments. You are encouraged to consider any additional challenges students might face resulting from change to the format of assessments and adopt inclusive approaches wherever possible. The Curriculum Framework pages on diversity and inclusivity provide a range of useful advice and guidance: Engaging Everyone and Diversifying Assessment.

Equally, to ensure parity, adapted assessment tasks should be the same for both campus-based and remote students, subject to the usual policy governing reasonable adjustments: Examination and assessment arrangements for students with specific needs.

Assessment criteria

Assessment criteria may need to be adapted to reflect changes made to the original assessment and/or changes to the assessment conditions. For example, the assessment criteria for an unseen in-class test might justifiably value students’ ability to recall facts or key theories and concepts; however, in a take home or open book exam, this criterion might be adapted to reflect the students’ ability to apply that knowledge, rather than simply restate it.

Bear in mind how you will support colleagues to ensure consistency of academic judgements, and support students to make sense of standards and criteria. Engaging colleagues in pre-marking calibration exercises in which a sample of student work is marked together can be very useful in constructing a shared understanding of levelness and expectations. Formative assessment activities in which students use the same assessment criteria with which they will be assessed are also recommended (see the section of Formative Assessment, above).

Assessment equivalence and workload

Any changes to assessment should take account of equivalence of effort on the part of the student. For example, if a module was previously assessed via a 3-hour unseen examination, what might be reasonably be considered the equivalent if it is now to be assessed by written assignment?

While some universities have developed guidance on assessment equivalency based on word limit (see below), this may be unreliable as an absolute indicator of equivalence as some shorter pieces may nevertheless require greater student effort than longer ones. Equally, not all assignments are as readily quantifiable as essays and reports in terms of word count and exams in terms of duration: how might an artwork or performance be quantified?

It is suggested that you estimate equivalence based on notional learning hours and estimated student effort, drawing on word counts and durations where useful, but otherwise relying on your academic judgement and experience. A useful rule of thumb is to assume that students should expect to spend around 25% of a typical module’s notional learning hours on assessment-related work (i.e., time spent interpreting and discussing the assignment brief, thinking, planning their approach, conducting research, drafting, revising and finishing, etc).

If adapting assessments, it is strongly recommended that programme teams take a shared view of assessment equivalence and workload to ensure parity and equity.

Further advice and information on approaches adopted at other institutions can be found here:

Academic integrity

Students who are used to completing written assignments for submission via Blackboard will be familiar with Turnitin and issues relating to originality. Students more accustomed to exams and similar approaches who now find themselves submitting coursework may be less familiar.

Developing familiarity with expectations

You are encouraged to ensure that students are fully aware of expectations relating to academic integrity and the use of Turnitin and other measures to determine academic misconduct. Full details of the University’s position on academic integrity are available in section 9 of the Assessment Handbook: Academic integrity and academic misconduct.

Further guidance for students and tutors can also be found in the Academic Integrity Toolkit.

Activities to develop understanding of academic integrity

Encouraging students to submit work via Turnitin prior to their deadline so they can access and interpret their similarity reports before final submission can be helpful. Exploring similarity reports in partnership with students as part of interactive sessions can also provide a useful opportunity for developing their understanding of how they use sources in their work.

Note that the option for producing similarity reports needs to be enabled when setting up the assignment.

For more information see here: Turnitin Similarity Report – Getting Started.

The following guidance provides advice on the range of options for converting traditional in-person exams into take-home assessments that students undertake remotely.

Summer Exams 2021 - Adapting exams to take-home assessments (CQSD)

The following guidance provides advice on Exam paper setting for online and in-person assessments.

Exam Paper Setting document - Online (Exams Office)

Exam Paper Setting document - In-person (Exams Office)

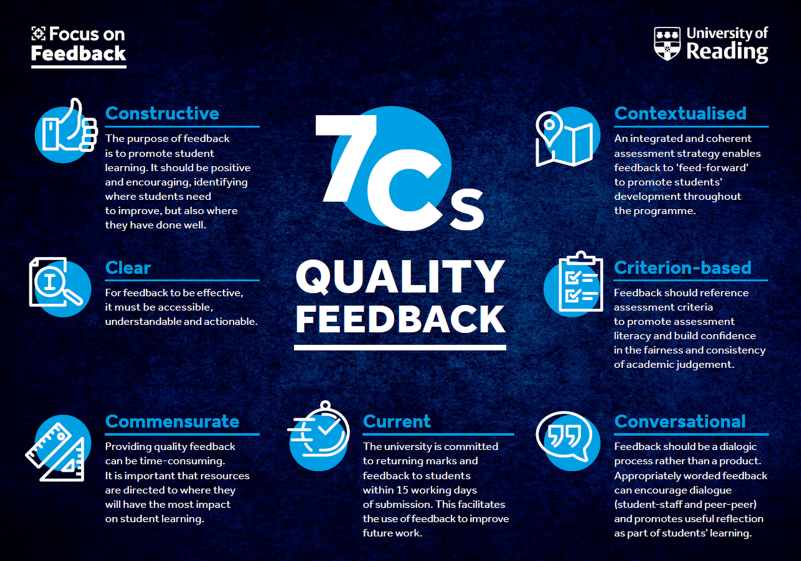

Feedback guidance

The ADE team have developed the following downloadable guidance and advice to support colleagues in giving quality feedback

The current situation, however, points to the usefulness of emphasising certain aspects of the feedback process to foster in students a sense of belonging to their learning community, to create opportunities for social connection and promote meaningful interaction between students and staff (Nordmann et al., 2020). Central to this is conceptualising feedback as a dialogic process rather than a product. In addition to providing feedback to students on how they are doing, including generic feedback to the whole group, you are also encouraged to adopt feedback practices which:

- emphasise the social and dialogic aspect of feedback

- involve students meaningfully as agents in the feedback process

- develop students’ feedback literacy (Carless and Boud, 2018).

Some strategies for doing this are outlined below.

A Talis Reading list aligned to these strategies is available if you would like to find out more.

Peer to peer formative feedback activities

Peer-to-peer activities can be an excellent form of formative feedback. A common approach involves students working in pairs to assess and comment on each other’s drafts, using the same assessment criteria that will be used to grade their summative assignments. This provides students with useful formative feedback from their peers but also, and perhaps more importantly, develops their own critical awareness in relation to their work, associated self-regulatory skills, and a deeper sense of what is valued in their disciplinary communities. This underpins the development of student appreciation of feedback and the ability to form judgements which is so integral to students’ developing feedback literacy.

Collaborative formative assessment activities also provide the basis for peer and tutor dialogue, multiple sources of feedback, and useful social interaction. Online tools such as Blackboard Wikis, OneNote and MS Whiteboard which enable students to co-author documents can be used in scheduled interactive sessions and asynchronous group activities.

Students are more likely to be able to engage meaningfully in peer feedback activities where they have access to appropriate resources (e.g. well-framed assessment criteria) and receive clear guidance in terms of what is expected of them as providers as well as receivers of feedback. Effective peer feedback activities require careful structuring and preparation if they are going to successful.

Video and audio feedback

Video and audio feedback add a useful human and social aspect to the feedback process which promotes a sense of connectedness and belonging. Use of video or audio may also enable you to provide feedback on students’ work in a time efficient way that is more personal, nuanced, and more focused on the ‘feed-forward’ elements of feedback.

Professor Cindy Becker outlining the benefits of audio feedback

Blackboard assignments: audio and video feedback

Turnitin: feedback studio – add audio feedback

In addition to using video or audio for individual and generic feedback, you could also encourage its use for formative peer feedback activities. Blackboard discussion forums can provide an accessible and easy to manage space in which students can share audio and video files for the purposes of providing formative peer feedback.

Formative online quizzes

Online quizzes provide useful formative self-assessment opportunities for students.

Informal quizzes, such as Blackboard Tests can provide a significant checkpoint for students engaging asynchronously through the provision of instant automated feedback to prompt reflection and direct future learning. A useful strategy is to provide hints and worked examples rather than correct answers and encourage students to have multiple attempts at the quiz.

There are also a range of ‘free’ apps you can use for quiz creation (e.g. Kahoot!, Mentimeter). When used in interactive sessions quizzes can also help you gauge the level of understanding of your students, facilitate active learning and provide opportunities for collaborative learning.

Maximising opportunities for student and staff engagement with feedback

For students

Feedback should not be something that simply happens to students, they need to be encouraged to engage with it, understand and act upon it. In addition to the support you provide, providing opportunities for students to work individually, and with each other to unpack feedback (on their own work or exemplars) and identify specific areas to focus on can be helpful in encouraging them to engage with and apply feedback to future work.

The Developing Engagement with Feedback Toolkit

Assessment & Feedback: Guidance for Academic Tutors

Making the most of your feedback (for Students)

For staff

To ensure you manage your workload effectively, programme teams are encouraged to focus their resources to ensure that students get the feedback they require when it is most useful to them. For example, feedback given at the end of a module is unlikely to be effective in terms of impacting upon future performance, unless there is a clear and explicit link to work in later modules. Formative ‘feed-forward’ given at a time that will allow students to respond to it in summative work within a module, however, is much more likely to be taken up and used. Where decisions have been made strategically to direct resource to the provision of more detailed feedback in some areas at the expense of others, it is important that this is conveyed to students with a clear rationale in order to manage their expectations.

Encourage students, too, to provide feedback on your feedback: What did they find useful about it? What was less useful? How could it be enhanced?

References

Carless, D. and Boud, D. (2018) ‘The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback’, Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), pp.1315-1325. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Nordmann, E., Horlin, C., Hutchison, J., Murray, J.A., Robson, L., Seery, M.K. and MacKay, J.R., (2020) ‘Ten simple rules for supporting a temporary online pivot in higher education’, PLoS Comput Biol 16(10): e1008242. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008242