By: Mat Haine, Centre for Quality Support and Development (CQSD), m.l.b.haine@reading.ac.uk

Each year, students like Brooke graduate from Reading and fulfil their aspirations.

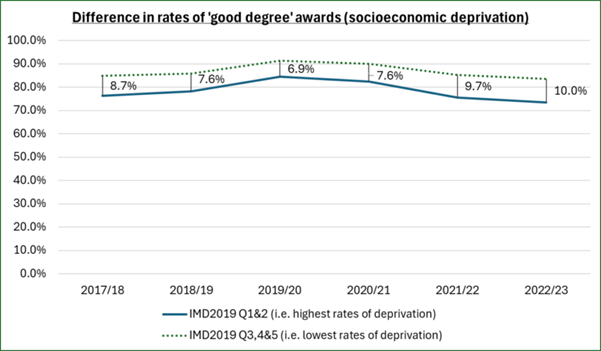

However, students from deprived neighbourhoods are disproportionately being left behind (see Figure 1.1 below). Reading students from deprived postcode areas are consistently less likely to stay on course, be awarded a strong result or land in employment, suggesting the playing field is not as level as we might think.

What is going on?

“I’ll never forget getting accepted at Reading. How proud I was. You know, if it never went any further than that, I would have thought I had achieved.”

Outcome gaps along the lines of class begin early and particularly affect white boys, pre-university. Government data shows that at 16, among those receiving free school meals, ethnically Chinese students are ‘39 months ahead’ of their white peers.

This is not inevitable. In the late 1990s, schools in London were among the worst performing in the country. After a period of substantial investment, outcome gaps for disadvantaged students have narrowed and London leads the country on attainment. This demonstrates that change is possible and learning environments make a difference.

Many working-class students who beat the odds to earn a place at our university come from schools in deprived areas and often rate the advice they received about higher education as ‘poor’. Their achievement reflects exceptional resilience and academic potential.

So why are they down on every outcome measure?

“They say ‘oh, your studies should come first’ but I just don’t have that choice.”

Our traditions are rooted in the idea of the ‘full time student’ which is becoming increasingly irrelevant. Our students are commuting, working and struggling more than ever. Shrinking finances and complex circumstances are undermining attendance and engagement. It’s easy to imagine how these pressures are more keenly felt by students from low-income households.

“If I say I’m struggling, I’m admitting to being ‘lesser than’”

Class inclusion is about more than time and money, though. There are subtle ‘currencies’ that students need to get by, like special knowledge and personal networks. Students with parents or siblings who went to university know how the system works; others must go out of their way to learn. We assume that bridging this gap is about telling students which buildings to go to, but support seeking taps into fear, pride and self-esteem. It relies on a sense of entitlement that is unfamiliar to students who worry that ‘needing help’ will confirm stereotypes about them.

“If you showed your true self, it will be considered either unprofessional, crude, or it may even come across as incompetent.”

Most students have the ‘right’ cultural presentation to move through our hallways with a sense of ease. That belonging is hard-won by working class students who feel pressured into concealing their accents for fear of triggering low expectations.

Before we ask students to ‘be themselves’ we must first reflect on how despite our good intentions we could be creating an environment that stifles authenticity.

So, let’s talk about how.

1. Talk about it

Reading, reflecting and talking about potential inequalities will make us more responsible educators and professionals. It will also allow for authentic identities to emerge – including in the classroom.

2. Teach the students we have, not the ones we want

The diversification of the student body includes a greater diversity of educational background, and many students now recruited based on potential. We should consider how adapting teaching and assessment styles could unlock that potential.

Digitally enabled learning is key for those who can’t guarantee attendance. Equally important is viewing the teaching process as being about teaching how to succeed as well as subject mastery. Overcoming the content-first instinct and making space in modules for assessment unpacking exercises would bring implicit knowledge out into the open for all to see.

3. Consider the critical moments

Transitions and assessments are points at which underrepresented students are typically more anxious.

Peer support, well-timed advice and ‘approachability’ could be the difference between a student withdrawing and going on to graduate. As could reframing ‘needing help’ to ‘backing yourself’ – an accepted behaviour common to successful students.

4. Think bigger

In an era of financial constraint, we can’t rely on extra-curricular initiatives. We need to do the difficult work of structuring support by building it into our systems.

Courageous programme design which accounts for attendance pressures, demystifies the hidden curriculum and destigmatises re-assessment could bring education from the past into the present, by truly centring it around the modern student.

This article was written for the ‘Celebrating Class’ blog series, exhibition and conference.