By: Emma-Jayne Conway, Charlie Waller Institute, School of Psychology and Clinical Language) emma-jayne.conway@reading.ac.uk

Overview

Educator self-disclosure can serve as a useful approach to creating inclusive learning environments and challenging traditional academic power dynamics. Educator self-disclosure refers to personal remarks made in a learning setting that may or may not relate directly to the subject matter, but nonetheless share information about the educator that students would not typically access through other means (Henry & Thorsen, 2018). When used thoughtfully, lecturers sharing personal and professional experiences helped model authenticity, validate diverse experiences and reduce the power imbalance between staff and students. This research highlights the value of using this approach to foster more inclusive and reflective learning spaces.

Objectives

- To explore the benefits and challenges of educator self-disclosure in cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) training from both student and educator perspectives.

- To examine the impact of educator self-disclosure on power dynamics in academic settings.

- To assess its potential to support inclusive, reflective teaching.

Context

Many students bring lived experience into the classroom, including mental health struggles, and statistics suggest that every year one in four people will experience a mental health issue (McManus et al., 2009). This research was inspired by my experience of disclosing a needle phobia in teaching, which was positively received by students and helped support their learning of the diagnostic criteria, assessment, and formulation of specific phobia.

Implementation

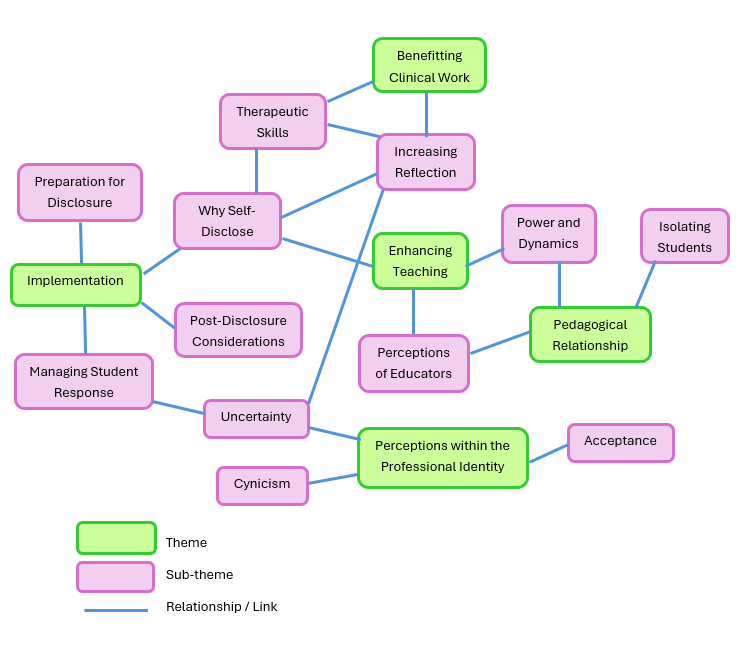

To explore perceptions of educator self-disclosure, semi-structured interviews were conducted with both staff and students to examine its perceived benefits, challenges, and influence on power dynamics. The data was analysed using thematic analysis to identify key themes (see Table 1 in the appendix and Figure 1 below).

Examples of self-disclosure from educators included their personal lived experiences with mental health and professional learnings from clinical practice. One educator commented “I think that it can sometimes support students who might also have lived experience as well, just to know that it’s normal and it’s OK”, a statement that reinforces the value of creating a supportive learning environment. Another noted how educators using their clinical experiences as a teaching tool can help students understand boundaries and appropriateness in therapeutic settings, “It can help us to model to our trainees what’s appropriate self-disclosure because obviously that’s something we want them to be considering of their own work.”

These insights were echoed by students, with one sharing, “I suppose you feel a bit more on par, especially when they tell you things they have not done so well, like mistakes they’ve made”. This participant described feeling more equal to lecturers when they disclosed professional mistakes, suggesting that such self-disclosure humanises educators and lessens the power imbalance in the room.

These examples demonstrate how educator self-disclosure can serve as a powerful pedagogical tool to foster academic relationships, normalise experiences, promote inclusivity, and reduce power dynamics.

Impact

This study achieved its objectives, with the key themes offering insights into how educator self-disclosure has implications for both pedagogy and CBT clinical practice. In the pedagogical context, the findings suggest that self-disclosure can humanise educators, reduce the power imbalance, and create more passionate teaching. The implications for CBT suggest that educator self-disclosure can increase student reflection, bridge the gap between theory and practice, and model appropriate self-disclosure as a therapeutic skill. However, the study also revealed that if disclosures felt irrelevant, they could alienate students and reinforce power imbalances, therefore highlighting the importance of context, intent, and boundaries.

Unexpectedly, there was a general, though not exclusive, difference in how educators and students defined the term ‘self-disclosure.’ Students tended to associate it with professional examples, while educators more often referred to personal experiences. As a result, students responded particularly positively to disclosures involving professional mistakes or challenges as these disclosures helped reduce feelings of perfectionism and self-doubt.

Reflections

This study was made possible by undertaking it as part of my EDMAP3: Academic Research and Practice project, which gave me the dedicated time and structure to carry it out.

A key strength of this project was the dual perspective of students and educators, which enriched the findings and provided a more rounded view of how educator self-disclosure is experienced and understood in the classroom.

The study could have been strengthened by giving clearer distinctions between personal and professional disclosure in the interview questions, which may have helped explore the differing interpretations of self-disclosure more explicitly.

Follow up

Based on this research, I will be looking to develop guidelines for educator self-disclosure, specifically within CBT clinical courses, and will seek to do a follow-up study to assess the impact of such guidelines on the teaching experience for students and staff.

References

- Henry, A., & Thorsen, C. (2018). Teachers’ self-disclosures and influences on students’ motivation: A relational perspective. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 24(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2018.1441261

- McManus, S., Meltzer, H., Brugha, T., Bebbington, P. E., & Jenkins, R. (2009). Adult psychiatric morbidity in England: Results of a household survey. Health and Social Care Information Centre. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-survey/adult-psychiatric-morbidity-in-england-2007-results-of-a-household-survey