Professor Maria Shaghedenova’s research looks at the shrinkage of glaciers due to climate change, and the effect of this on rivers and lakes.

Her work recently featured in a visually stunning interactive New York Times piece about melting glaciers in Kazakhstan. Here, she tells CONNECTED about the science behind the story.

“The New York Times story originates from our research project Climate Change, Water Resources and Food Security in Kazakhstan which was funded in 2015-17 by the Newton – al Farabi Fund. Our main collaborators were the Department of Glaciology at the Kazakhstan Institute of Geography (KIG) led by Professor Igor Severskiy.”

Soviet era weather station

“We started collaborating with KIG, which runs several high-elevation meteorological-glaciological stations, in 2009. The most important of these stations is the Tuyuksu Mountain Observatory, at 3438 metres above sea level, established during the Soviet Era in 1957/58 (the First International Geophysical Year) at the tongue of the Tuyuksu glacier.

“Tuyuksu is one of the world’s reference glaciers – that is, one of a network of glaciers which are regularly measured coordinated by the World Glacier Monitoring Service.

“The station is particularly significant because it has such a long record, and the KIG managed to keep it going after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when most monitoring facilities in Central Asia were closed.

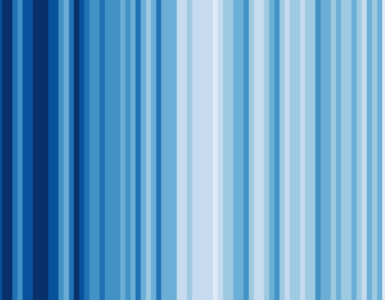

“The station took mass balance measurements [a measure of a glacier’s health] but also made basic manual meteorological measurements. In 2015, using money from the project, we installed several automatic weather stations with a full range of micrometeorological measurements forming a vertical profile from 600m on the plain all the way to Tuyuksu (this is what you see on the final image in the New York Times piece).”

Steady shrinkage

“In our project, we documented glacier change in the region in terms of its area (a decline of 1% per year since the 1950s), volume and mass balance. We assessed changes in climate using historical data from high-altitude stations and we put together an archive of water discharge data from the region. Data from several natural catchments were analysed for trends.

“Our main conclusion was there had been no negative trends in discharge since the 1950s, but some increase since the 1970s, which is when most observations start.

“As part of our research, we ran regional climate models for Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reports to generate future climate scenarios and used a hydrological model to simulate future changes in discharge from the glacier. Our main conclusion was that peak flow has already been reached and will continue until the 2040s. We expect to see a decline in water discharge from the glacier in the summers afterwards.”

Wasted water

“We also collaborated with local farmers to gather data on crop production and water use for irrigation. We found the irrigation system to be in a very poor state with inefficient use of water.

“The local Kazakhstan administration often says that there is no water due to climate change, so they were quite surprised when we said that currently, there is more of it than there used to be! Crop models have been set up to assess how the lack of water may affect crops in the future.

“Our work in Kazakhstan continues, and together, with KIG we have won several new grants to work in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan.”

Find out more about Professor Maria Shaghedenova’s research.

This article was first published in the New York Times on 17 April 2019.