As COVID-19 has spread, a growing number of people’s mental health has negatively been affected – not so much by the virus itself – but by the response to it. Dr Paul Jenkins, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology at Reading, explains how those with eating disorders have been impacted.

Recent studies show many people with conditions such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorders experienced a worsening of symptoms as well as increased anxiety in the early stages of the COVID-19 outbreak.

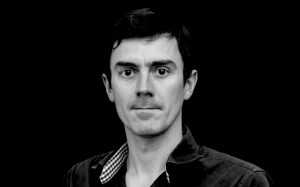

Dr Jenkins from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, focuses on how we can support people who are struggling with their eating and mental health during the pandemic.

Dr Jenkins from the School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, focuses on how we can support people who are struggling with their eating and mental health during the pandemic.

He explained: “It’s too early to state conclusively the reasons for why these conditions have worsened, but it’s clear the pandemic and subsequent containment measures have disrupted everyday activities and changed routines. This may have left people feeling out of control, which can influence eating behaviour.

“On top of this, the stress of living in the shadow of a life-threatening virus and even greater barriers to accessing treatment may have resulted in a greater focus on weight and shape. This in turn may have brought about changes in eating behaviour, such as ‘stockpiling’ certain foods or using food for emotional comfort.

“Given these challenges, I want to focus on how to support people who are struggling with their eating and mental health. These are some practical steps that anyone can take to mitigate the effects of the recent upheaval, which can be considered in addition to formal interventions provided by healthcare professionals.”

Regaining control

Dr Jenkins explains that one way to start the process of reasserting control is to re-establish structure, which will not only help manage the process of eating itself, but will also promote consistency and a reliable schedule across several areas of life – something many of us have struggled to find during lockdown.

He said: “Try creating a plan for eating that follows some simple guidelines around regularity – for instance, breakfast-snack-lunch-snack-dinner, no more than four hours apart. This may result in greater insulin sensitivity [where our cells use blood glucose more effectively] and help with healthy weight control.

“There’s also some evidence from treatment studies that regular eating is associated with early decreases in behaviours such as binge eating. There are also likely to be wider benefits, too. For example, sleep and eating are closely interrelated.

“The key to keeping both healthy is consistency: sticking to a regular sleep schedule can help with regular eating and vice versa.

Social eating

The restrictions imposed in response to the pandemic have also put constraints on our social lives. Dr Jenkins advises that achieving stability in one’s life (where eating is not the sole focus) can help reignite social interaction and also occupy the mind when concerns about eating, weight or shape arise.

He said: “For many, leading a more restricted life under lockdown will have internalised worries, taking away the unique pleasure of social eating and elevating current stressors.

“Returning to a life where mealtimes forge connections with others and where ‘real life’ can be seen – warts and all – will help overcome some of the psychological risks posed by the lockdown. For those shielding or otherwise unable to go out, consider arranging a meeting online.”

Handling stress

Dr Jenkins also highlights that positive and effective ways of dealing with stress can help when things don’t go to plan.

He explained: “The exact nature of coping can vary [common strategies include mindfulness, arts and crafts, exercise, gardening and other hobbies] – the key is to find something that works for you.

“When dealing with eating problems, one has to be careful that coping strategies [particularly those involving exercise, even something as seemingly innocuous as walking the dog] are not ‘hijacked’ to manipulate weight.

“Pairing them with social activities [such as going for a walk with a friend and ending with a drink and a snack as part of planned eating] can both reduce the harmful effects of disordered eating and promote the benefits of social interaction.”

Manage unreasonable expectations

Our relationships with our bodies are complex. Dr Jenkins stresses that the effects of the pandemic may have brought about a focus on ourselves like never before, which will have exacerbated body image concerns for many.

He said: “Creating new ways of coping [or, perhaps, returning to old ways] may be a particular relief after a period of ‘hustle culture’, in which lockdown has been perceived by some as a time to do more, not less. People’s bodies are not immune from such pressures and demands, with the lockdown creating new expressions such as the ‘Quarantine 15’ [a reference to the number of pounds people might gain during isolation] and memes related to the association between quarantine and weight gain.

“Messages around weight and expectations of excessive productivity can be particularly stressful for those with eating concerns, and result in a vicious cycle where vulnerable people either turn to food or away from it to manage impossible demands.

“Nurturing a healthy relationship with your body [and, by extension, yourself] is key to managing disordered eating. Indeed, many of those who recover from eating disorders cite the capacity to be kind and compassionate to themselves as the ‘final stage in the process of recovery’.

“Many therapeutic approaches argue that recovery from an eating disorder is found through pursuing a healthy way of life, citing research suggesting that over-focus on our bodies can directly affect eating behaviour.

“For those suffering with eating disorders, there are several evidence-based treatments available. Many current treatments align with the suggestions above. For example, approaches based on cognitive behavioural therapy or family-based therapy [both recommended psychological treatments] encourage healthy, planned eating and cover issues such as managing emotions and social-skills training.”

For more information about these treatments – including how to access help – speak to a healthcare professional.

Find out more about Dr Jenkins’ research.

This article was first published in The Conversation on 17 August 2020.