Professor Nick Branch and Dr Mike Simmonds, SAGES.

.

Context

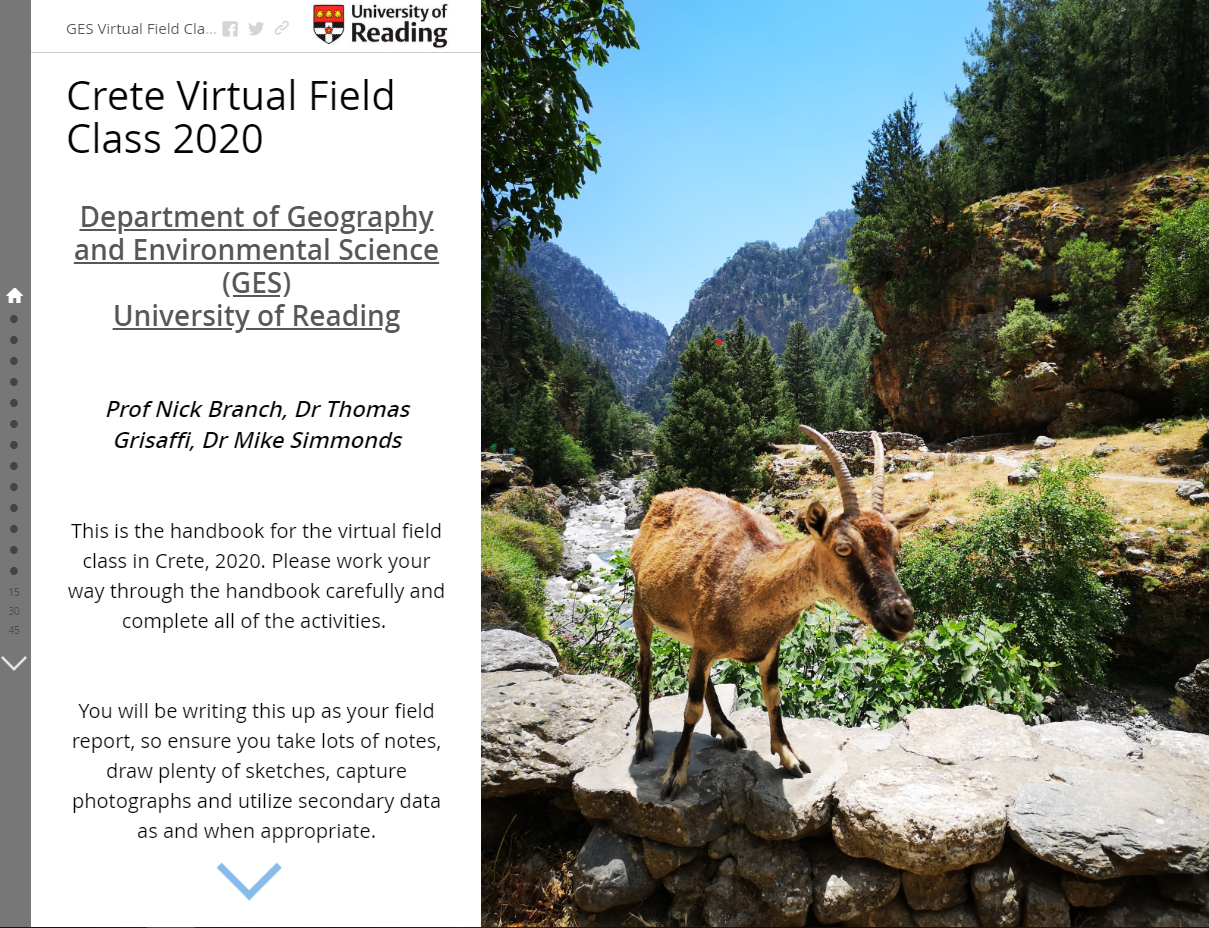

The rapid closure of universities and cancellation of outdoor activities as part of the COVID-19 precautions prior to Easter 2020 led to widespread adjustments to teaching delivery methods across the university sector. Seemingly overnight, lectures were given online, meetings were migrated and everyone (slowly) became experts in video calling. In Geography and Environmental Science, we also faced an additional problem, how to provide our students with the field-based teaching elements of their courses, when access to the sites was restricted. Geography and Environmental Science run four Part 2 fieldtrips to Europe (Almeria, Berlin, Crete and Naples), a Part 3 fieldtrip to Nanjing in China and a MSc trip to Devon across the end of the Easter vacation and the start of the summer term, so the timing of the lockdown meant we needed to find a new way of teaching these important geographical and environmental science skills to our students. We needed to find a delivery method that would allow students to explore the outside world whilst they were at home, with tasks and activities designed to enable them to collate, analyse and present their findings. The ‘Virtual Field Class’ (VFC) was born.

Implementation

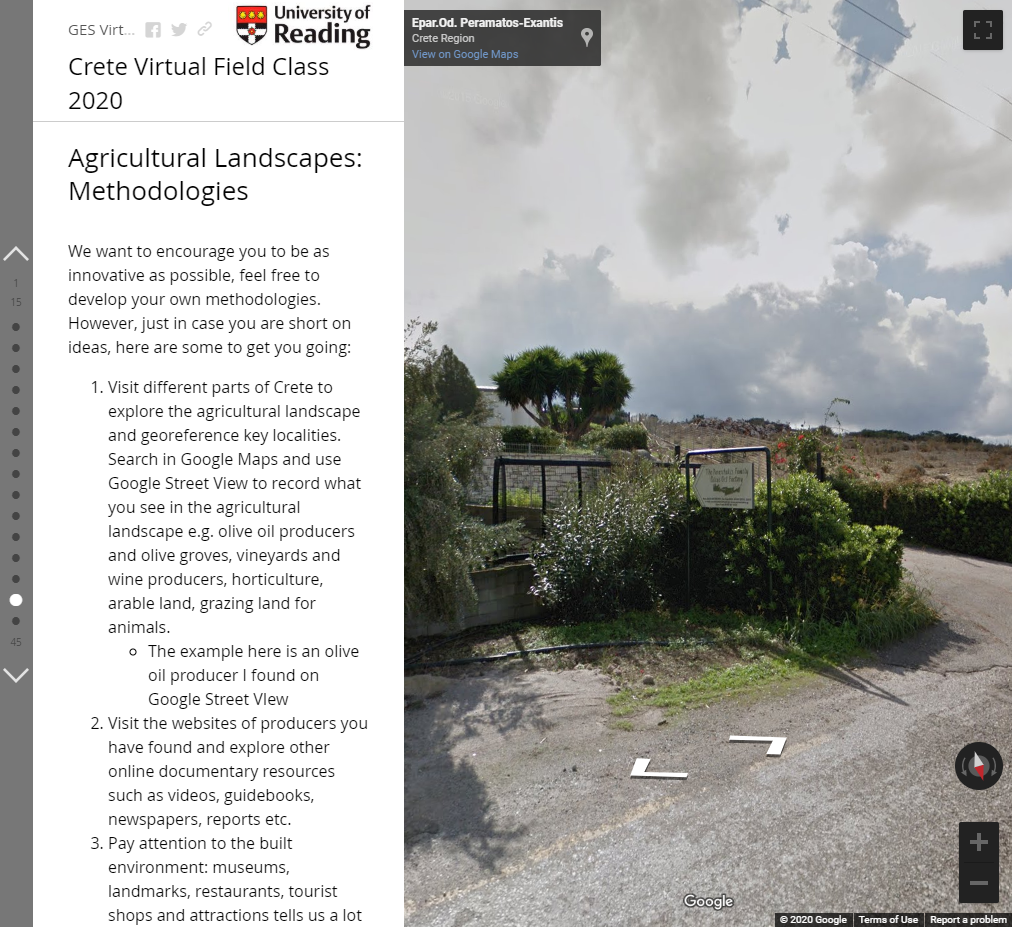

It quickly transpired that one of the key elements for the VFC to be successful was imagery, with enough required so that the students could fully explore those regions we would traditionally visit on the field classes. Google Maps Street View was chosen for this, as it provided an excellent, expansive, and high-quality array of both street level imagery and 360-degree photospheres which would allow students to explore at their own pace, and in their own direction. However, without a clear and coherent narrative accompanying these images, this was clunky, convoluted and it difficult to envisage a high level of engagement or student satisfaction. Field class leaders also wanted to be able to showcase images, videos, maps, and other content alongside Street View imagery, so a better framework was needed to host this range of VFC content. Based on previous experience, it was decided to use Esri Story Maps to act as the framework for this array of material. Nestled within the Esri suite of apps and programmes, Esri Story Maps is a powerful online tool, which staff and students can access through our Esri agreement (there are two versions; Esri Story Maps (classic) and ArcGIS StoryMaps – both provide similar functionality). Story Maps provides a platform for text, images, maps and other multimedia content to be hosted in an engaging narrative, which can be followed in a pre-determined order; much like a traditional field class. Another important consideration was ease of use of the platform, due to the limited time available to assemble these VFC’s, and again Esri Story Maps were ideal here, with field class convenors quickly understanding the key elements of the platform with minimal training.

Impact

The methodology used to create the VFC has not only provided a temporary substitute for face-to-face field-based training but also highlighted the value of using this digital resource as part of our research skills teaching. Our usual pre-field class assessment consisted of a short essay or PowerPoint screencast. This was intended to familiarise the students with aspects of the human and/or physical geography of each field class location. Whilst these forms of assessment have their benefits, in future a modified version of the VFC will be used because it permits students to visually and interactively explore the wider rural and urban geography before departure. It will enable students to integrate textual and visual sources, contextualise key secondary data, collect geospatial data, and improve cartographic skills, knowledge of geospatial technologies, and general ICT abilities. Excellent preparation for a successful field class.

Reflections

The process of designing and running the VFC using Esri Story Maps as a platform has made us reflect on its wider application. First, modified versions of the VFC can be used for recruitment and applicant engagement events. For example, we are currently designing three online undergraduate events for Geography and Environmental Science (GES) of varying duration: 1 hour for current applicants, 2 hours for individuals or groups from schools/colleges, and 3 days for a Reading Scholars summer school. Secondly, laboratory-based practical classes could also utilise Story Maps. For example, we are exploring capturing images of specific microscopic (e.g. pollen grains and spores) and geological specimens used in GES part 1 teaching as a guide to identification and linking these to other online textual and visual resources. The guide will be used as a preparatory exercise for a practical examination.