In honour of Women’s History Month CONNECTED explores the trailblazing discoveries of Tina Negus – from discovering a fossil, to undertaking one of the first quantitative mussel surveys.

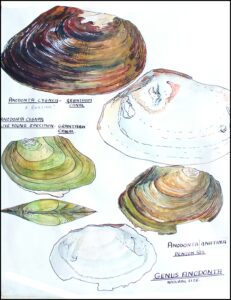

Tina’s interest in natural history led her to choose to study zoology, botany and geography as an undergraduate at Reading in the 1960s. With her scientific gaze focused on the River Thames, Tina conducted one of the first quantitative surveys to evaluate freshwater mussel populations in 1964.

Tina’s interest in natural history led her to choose to study zoology, botany and geography as an undergraduate at Reading in the 1960s. With her scientific gaze focused on the River Thames, Tina conducted one of the first quantitative surveys to evaluate freshwater mussel populations in 1964.

Six decades on her endeavours continue to provide valuable insights into the health of England’s longest river, as University of Cambridge PhD student Isobel Ollard revisited Tina’s research methods late last year.

Tina, who grew up in Grantham, Lincolnshire, said: “I was offered the opportunity to undertake the research by Dr Ken Mann, who was my supervisor, and I jumped at the chance. Despite the fact that it involved traversing a heavily-polluted, musty Thames in an extremely heavy boat in fairly miserable, cold and wet weather to collect samples.

“I suppose this was the first time the study had been done in this country and was part of a trend at that time; ecology was becoming quantified.

“Because it was quantitative, it lends itself to being repeated, but I never thought that someone would one day repeat the study – it never occurred to me. The news that Isobel was repeating my study came out of the blue and I was delighted.”

Decades of change

The intervening years showed a marked difference in the research findings. The data collected by Tina demonstrated an abundance of freshwater mussels in the river, whereas Isobel’s return to the same stretch of water showed a scarcity of shelled invertebrates.

The intervening years showed a marked difference in the research findings. The data collected by Tina demonstrated an abundance of freshwater mussels in the river, whereas Isobel’s return to the same stretch of water showed a scarcity of shelled invertebrates.

Over 50 years later, the Cambridge scholar found the molluscs – which help to filter water, remove algae, and provide places for other aquatic species to live – have been almost completely wiped out in the intervening years.

The mussels’ mathematical decline may, however, not all be bad news for the Thames. Noting the subjects of her original study feed off organic matter, which is common in sewage run-off, Tina argued their demise could be an indicator of improved water quality. She said:

“Over the past 50 years, we’ve had increasing control over pollution thanks to the European Union. There’s also been the development of an awareness that we’ve got to look after the environment.”

Correcting history

Tina’s scientific discoveries extend beyond the banks of the Thames. In recent years Tina was acknowledged for discovering Charnia Masoni – the first Precambrian fossil to be formally recognised by geologists.

The leaf-like fossil was originally presented to scientists in 1957 by – and duly named after – schoolboy Roger Mason, whose father worked at Leicester University. However, it has since been confirmed that Tina made the discovery a year earlier in Charnwood Forest, Leicester, as a 16-year-old.

The leaf-like fossil was originally presented to scientists in 1957 by – and duly named after – schoolboy Roger Mason, whose father worked at Leicester University. However, it has since been confirmed that Tina made the discovery a year earlier in Charnwood Forest, Leicester, as a 16-year-old.

She said: “My initial excitement over a rubbing I took had been dampened and dismissed out of hand by my secondary school geography teacher. I knew nobody and hardly knew what a university was in those day. I was just interested in rocks and fossils.

“It’s hard to put yourself back in those times. When I was a teenager – a female teenager – you weren’t taken much notice of, and I didn’t know who to ask about this fossil. I didn’t even consider it. I mean, back in the day, it was just assumed that what men said went.”

Since history was corrected on the 50th anniversary celebrations of the discovery of Charnia Masoni – when Dr Trevor Ford, a senior lecturer in the geology department of the University of Leicester and other geologists, corroborated Tina’s claim – her name has been further immortalised.

The University of Reading has since commissioned an accolade in her honour, with the inaugural Tina Negus Prize presented to a graduate of the School of Biological Sciences in 2019.

Read about Isobel Ollard’s research into mussels in the River Thames in The Conversation.