Dr Robin Poole – Reading graduate, esteemed scientist and nature enthusiast – talks to CONNECTED about his pioneering research into arthritis, and why the University of Reading will always hold a special place in his heart.

Dr Poole created, and from 1977-2005 led, the Joint Diseases Lab at McGill University in Montreal, Canada which became a world leader in arthritis research. His pioneering research identified new therapeutic targets to stop and treat joint damage in arthritis, as well as the development of blood and urine biomarkers to detect the onset and progression of arthritis and its treatment.

Fulfilling a promise to his wife – also a Reading graduate – Robin retired from full-time research at the age of 65. But his love of science prevailed and he has spent his retirement helping young researchers to conduct and publish their work, as well as consulting. He has also been heavily committed with the Cooper Marsh Conservators in protecting and restoring a local conservation area, as well as helping look after the St. Lawrence River with the River Institute for Environmental Sciences in Cornwall, Ontario.

Fulfilling a promise to his wife – also a Reading graduate – Robin retired from full-time research at the age of 65. But his love of science prevailed and he has spent his retirement helping young researchers to conduct and publish their work, as well as consulting. He has also been heavily committed with the Cooper Marsh Conservators in protecting and restoring a local conservation area, as well as helping look after the St. Lawrence River with the River Institute for Environmental Sciences in Cornwall, Ontario.

Dr Poole sat down with CONNECTED to reflect on his impressive career and share how it all began.

A rocky start

Dr Poole studied microbiology, chemistry and zoology at Reading, but the start to his career was hardly straightforward. He explained:

“I originally arrived at Reading with a view to becoming a marine biologist, but asked to switch courses to microbiology – luckily my tutor agreed. I turned out to be quite good at it and really enjoyed my studies and my first research project.

“However, I became somewhat distracted when I met my future wife, Mary Sawyer [who studied at Reading in 1959-62], in my second year. I also suffered a hand injury which meant I had to dictate some key exams. These two factors led me to graduate with a third class honours degree that prevented me from pursuing further studies.”

A lack of a PhD prevented Dr Poole from embarking on his chosen career as a research microbiologist in academia. Instead, he went into industry working with dangerous bacteria where he was able to perform independent studies in the lab. However, he soon became frustrated when he realised he couldn’t publish important discoveries and share his findings with others, because of company policies.

Dr Poole then moved into cancer research, inspired by his father’s experience of beating life-threatening spine cancer. However, he still felt stuck professionally. With the only way to progress being a PhD, Dr Poole asked Reading if they would supervise him working as an external graduate student in his spare time.

He said:

“If Reading hadn’t given me a second chance to prove myself capable for graduate studies, then we wouldn’t be speaking today about my career.

“Initially I was asked to prepare, over six months, a literature survey of my proposed topic for research. It was accepted – I spent four years working in evenings and weekends and in 1969, I finally completed my PhD on the role of lysosomal enzymes in tumour invasion.”

Seizing opportunities

Despite the complicated journey, if it wasn’t for Dr Poole’s venture into cancer research he may never have arrived at his career-defining arthritis research.

He explained: “My PhD studies at the cancer research institute focused on tumour invasion. Specifically, on investigating the edges of tumours – by researching the degradation of xiphoid cartilage, at the bottom of the sternum, caused by a transplantable tumour.

“Because of this work and my technical expertise, I was invited to Cambridge for a week to help researchers with a project refuting other published work involving related degradative enzymes in cartilage damage in arthritis. This week’s work resulted in a paper published in the prestigious journal Nature.”

Dr Poole was then offered a full-time position at Cambridge, before his boss recommended him to lead a new arthritis laboratory at McGill University in 1975.

Dr Poole reflected: “I didn’t believe the offer to start with, but after much back and forth planning between Montreal and the UK I moved there in 1977, with Mary and our three children, to become Director of the Joint Diseases Laboratory.

“This job was a fantastic opportunity to design my own lab, work on whatever I wanted in the area of joint disease, and the freedom to appoint my own staff. To go from struggling to start my career in microbiology, to running my own lab aged 37 was very exciting!”

Groundbreaking research

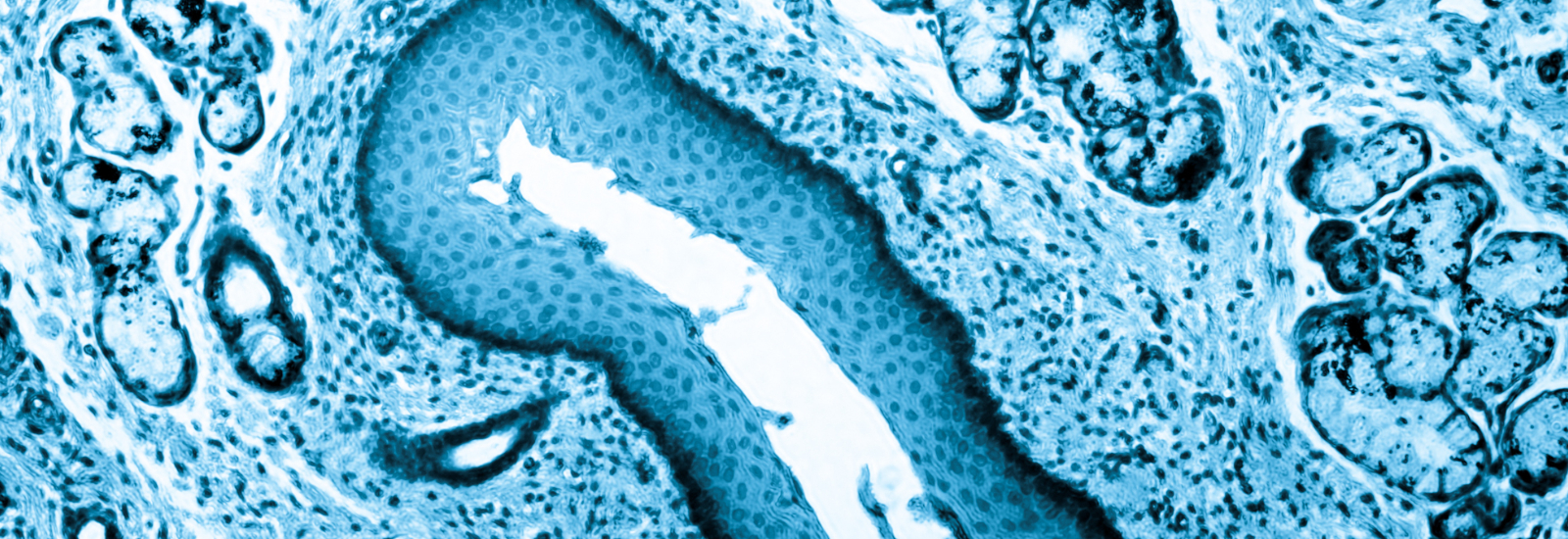

Most of our joints are covered by a tough tissue called cartilage (aka gristle) that, together with joint fluid, provides almost frictionless movement. One of Dr Poole’s pioneering arthritis discoveries was the development of immuno-assays to detect how a key molecule called cartilage type II collagen, which normally holds this very tough tissue together, is destroyed by degradative enzymes and cannot be repaired.

Dr Poole said: “These enzymes are called collagenases. The immuno-assays can be used in patients to monitor joint damage caused by these enzymes as it occurs. The development and manufacture of the latest urine assay for osteoarthritis [OA], C2C-HUSA, took place following my ‘retirement’. It was made possible by my collaboration with IBEX, a company based in Montreal.

“Based on our earlier work, we can now measure joint destruction in patients as it occurs in OA and rheumatoid arthritis. This is of great importance since in OA there are no disease-modifying drugs to arrest this damage, although about 15% of adults suffer from OA.

“This leads to the question – why had previous two year long trials failed to find a treatment? Well, we know now that knee joint cartilage damage occurs in phases, not as a continuous process.

“So to set up a clinical trial for OA drug development, you need to be able to identify patients with knee OA [where the disease activity can be measured radiographically] who are in a phase of progressive joint damage. Looking back, researchers discovered that about only one quarter of patients in previous trials had progressive joint damage. Without a preponderance of ‘progressors’ in a trial it was virtually impossible to identify whether a drug could slow or stop this damage. We probably missed some potentially effective treatments in all the trials that have taken place in recent years.”

This new assay was recently recognised after two-three years of independent study by the Foundation for National Institutes of Health, USA as the only clear measure of active joint destruction in knee OA. Dr Poole said:

“This should make it possible in the future to identify disease modifying drugs in clinical trials and to determine their effectiveness in months rather than over two-three years as in the past.

“The same biomarker is also proving to be of value in identifying about 25% of patients, probably with more severe knee OA, that will likely not experience pain relief and improved joint function following total joint replacement surgery.”

The highest recognition

These and other studies resulted in Dr Poole receiving many international awards in the last 30 years. In 2020, he was awarded the Order of Canada for his contributions to medical education and in recognition of his groundbreaking research on cartilage and its detection and treatment.

Dr Poole said: “My love is for science, so to receive this honour is terrific, but also humbling.

“To think that I came to Canada from Britain as an immigrant and had to start from scratch – it’s wonderful that my contributions are seen so positively and are so highly regarded by my country of adoption.

“We miss England – especially the family and close friends we don’t get to see as often now – but we love Canada and all the opportunities it has offered our family. It’s a very special place.”

A family man at heart

It is evident from speaking to Dr Poole that his family have provided a constant source of inspiration and support throughout his life.

He recalled: “It was my father’s gift of a microscope as a child – which I still own today – that got me interested in a career in microbiology. Our cat developed a fever when I was young and I was convinced it had picked up an infection from drinking drain water. So I collected a sample of water, examined it under my microscope and found loads of bacteria. It was a simple investigation but it set my mind working on my future.

“My father inspired me once again when he beat cancer – he was given six months to live, but a successful experimental radiation treatment in 1946 meant he lived to age 70. That set me on the path to work in cancer research which proved very successful.”

While much of the inspiration for his career may have stemmed from his father, it’s Dr Poole’s wife and children who were vital to his success.

He reflected: “My career would not have been possible without the support of Mary and my children – Jenny, Lucy and Jonathan. Mary has been incredible, giving up a career in mathematics for me, moving to Canada, leaving her sick mother behind, and raising our children.

“I feel very blessed to have lived the life I’ve lived, met wonderful people, and achieved the things I wanted to achieve. I feel humble and grateful to my family for making this life possible.”

A generous supporter

The University would like to extend its gratitude to Dr Poole for his generous support of the University community, especially his recent decision to support our research into COVID-19 antibody testing and our Student Hardship Appeal.

Dr Poole said: “Mary and I support a number of causes which are close to our hearts. We choose to support Reading’s community because it is so special to us and was so vital to my career. I wouldn’t have had my career at all if Reading hadn’t given me a second chance – I’m completely indebted to the University.

“My advice for students is to keep knocking on the door and never give up – where there’s a will there’s a way.”

To join Dr Poole in supporting our Student Hardship Appeal, find out more.