By: Dr Anna De Amicis, Henley Business School, a.deamicis2@reading.ac.uk

In the years since the pandemic, digital platforms have become a familiar presence in university classrooms. Padlet, Miro and Mentimeter are often presented as ways to boost interaction, make lectures more engaging, and give students new ways to share ideas. But their effectiveness depends less on the technology itself and more on how we, as educators, choose to integrate them.

Why Padlet?

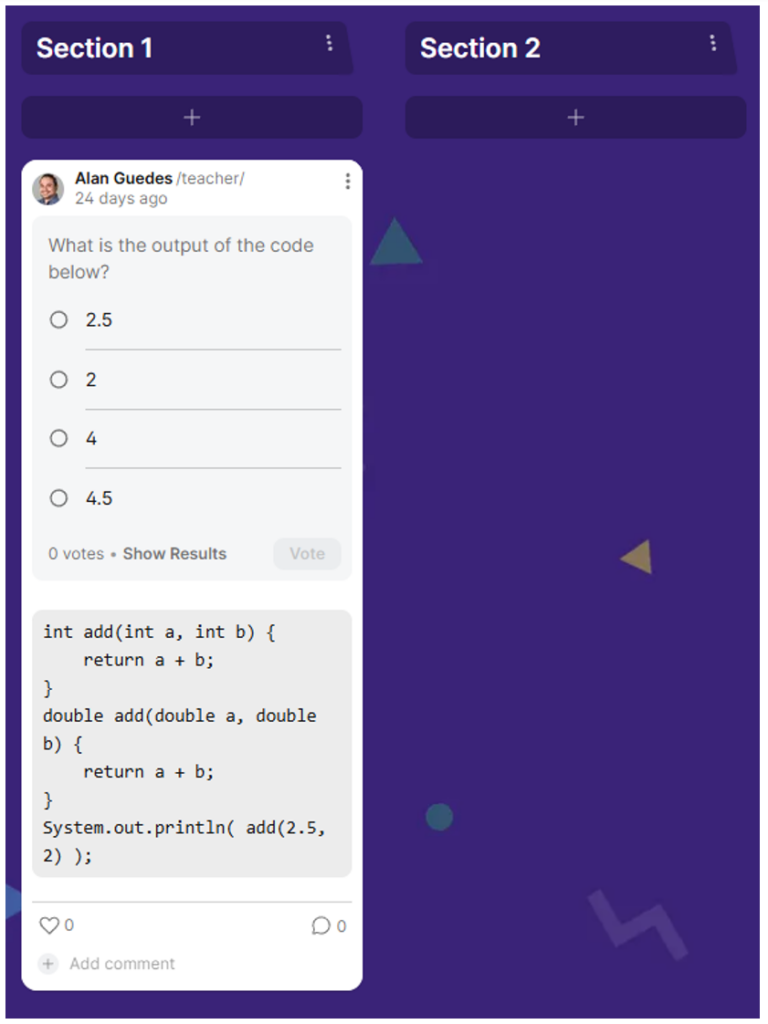

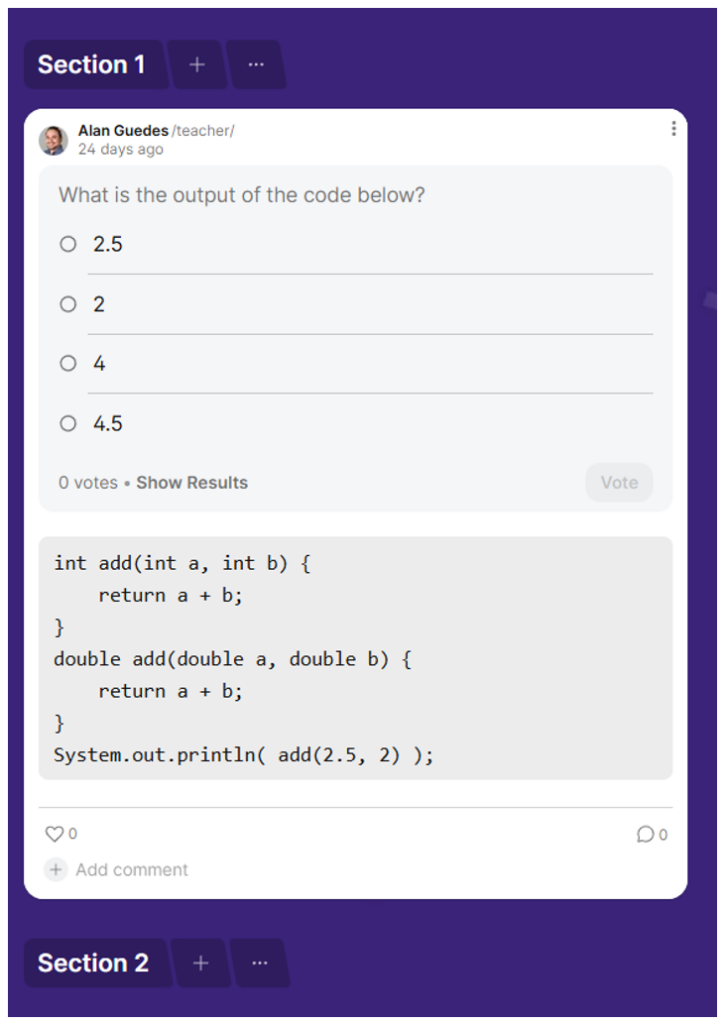

When I introduced Padlet into my social enterprise teaching, my aim was not simply to try out the latest tool. I wanted to encourage more discussion, present concepts visually, and make students’ contributions visible and connected.

Padlet offered a creative space, a digital canvas where students could post images, examples and reflections. It promised to energise the classroom, turning abstract concepts like “mission statements” into something students could critique, rework and co-create together.

What worked (and what didn’t)

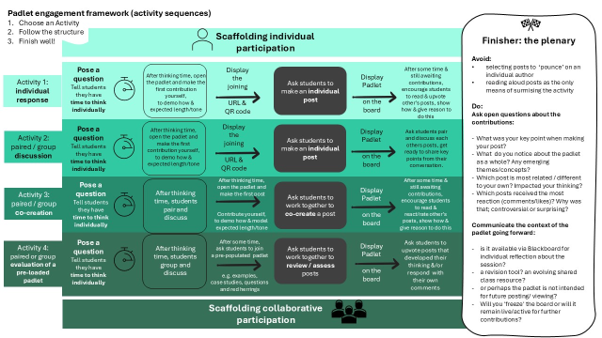

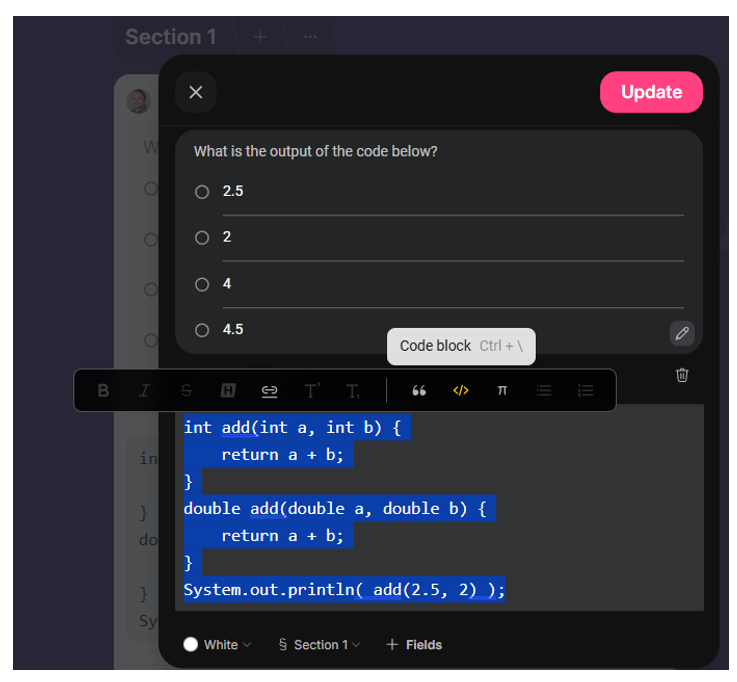

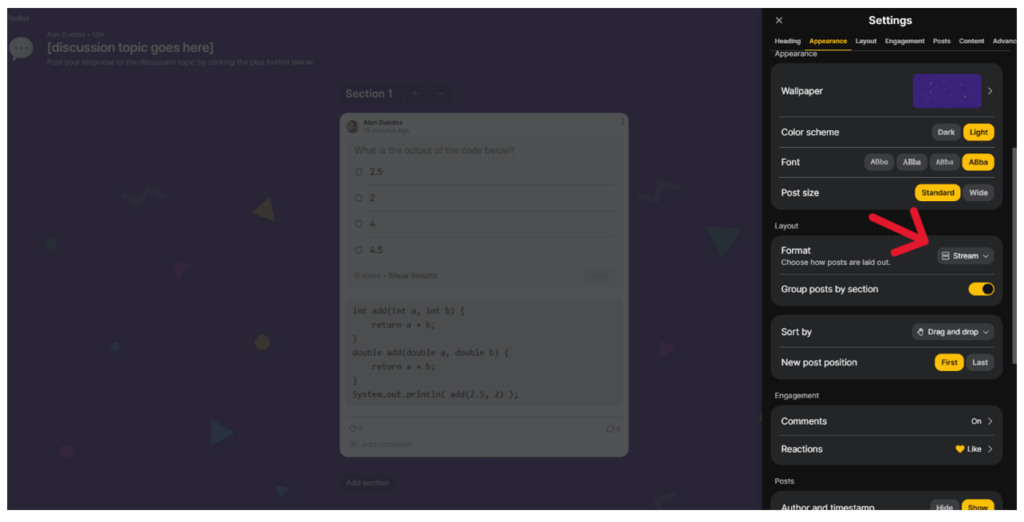

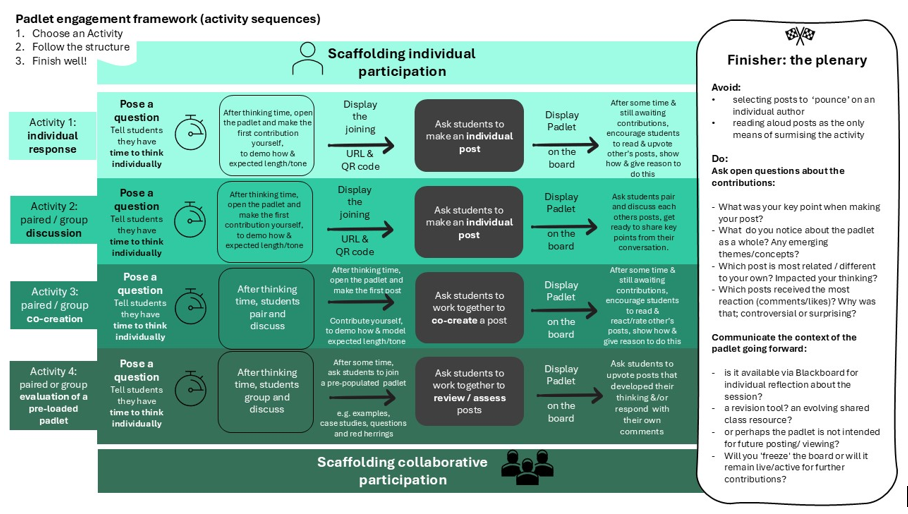

In practice, some aspects worked well. When I co-facilitated with a colleague (Jacqueline Fairbairn from CQSD-TEL), the prompt was better received, and students were more responsive. Structured tasks – such as asking students first to find a mission statement, then critique it, then collaborate on improvements – helped scaffold their learning. In these moments, Padlet supported active engagement. Frameworks can help here as shown in the Padlet engagement framework (see Figure 1.1), which sets out clear activity sequences from individual reflection through to group co-creation and evaluation.

However, there were also times when Padlet fell flat. Used as a quick ten-minute add-on, it disrupted the lecture flow. Students sometimes saw it as “extra work” rather than as part of the lesson. Interestingly, in sessions where we focused purely on facilitation and dialogue, the energy and depth of conversation were even stronger.

Lessons learned

The experience underscored an important point: the value of a digital tool depends on how well it is aligned with the purpose of the session. Students engage most when they clearly see the relevance of an activity and how it links to their learning outcomes.

This is not so much a limitation of Padlet as a reminder for us as lecturers to be intentional. Any classroom activity (whether digital or low-tech) needs meaningful design, clear integration, and facilitation that draws students in. Sometimes, the simplest methods can achieve just as much as a digital platform.

Wider implications

In business education, and particularly in teaching vocational modules, we often emphasise using resources wisely and with purpose. The same principle applies to teaching practice. Innovation in the classroom is not about adopting every new platform but about making deliberate choices that serve our students’ learning.

Digital tools have become part of higher education, and many can be genuinely valuable. But adopting tools because they look innovative is best avoided. What matters is that students experience activities as meaningful, purposeful, and connected to their learning journey.

Reflections

Padlet reminded me of a simple truth: students want to understand the value of what we ask them to do. They respond positively when they see how an activity supports their learning.

So, the real question may not be whether we need Padlet, but how we, as educators, design experiences that are intentional and values led. Technology can play an important role, but only as part of thoughtful, purposeful teaching practice.