By: Dr Andrea Tresidder and Dr Alicia Pena Bizama, Henley Business School, a.tresidder3@reading.ac.uk and m.a.penabizama@reading.ac.uk

Overview

We designed, piloted and evaluated a series of wellbeing resources specifically for apprentices to better support their wellbeing. These resources were created with learners’ and employers’ feedback and demonstrate Henley’s commitment to improve and protect wellbeing for our apprentices.

Objectives

The project aimed to

- Create wellbeing resources for learners focused on challenges of studying while working

2. Embed and integrate these resources consistently in degree apprenticeship programmes.

Context

Like all employees and students, learners on apprenticeship programmes need ongoing support to maintain their wellbeing. Henley is committed to creating a wellbeing-focused culture, yet current wellbeing resources fail to address the unique challenges experienced by this type of learner who are both employee and student. Embedding tailored resources into professional practice modules ensures learners receive consistent, relevant wellbeing support.

Implementation

The steps taken to carry out the activity were:

- Conducted a needs analysis by conducting surveys and informal discussion with apprenticeship learners to identify specific wellbeing challenges related to balancing work and study.

- Audited existing wellbeing materials to assess relevance and identify gaps specific to the dual role of apprentice learners.

- Worked collaboratively with an occupational psychologist to co-create new resources addressing motivation, procrastination, fear of failure, understanding perfectionism, stress and managing work and study.

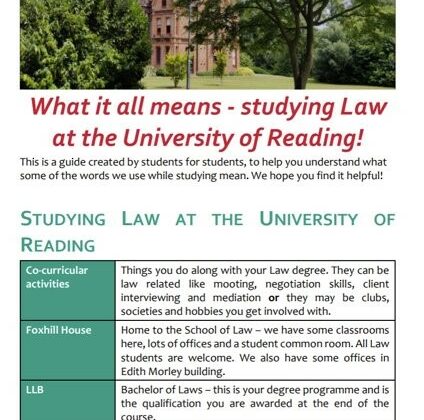

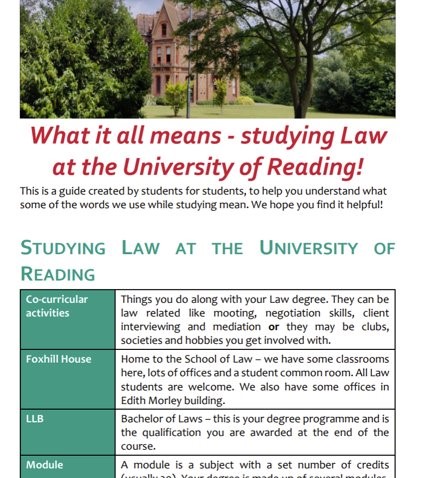

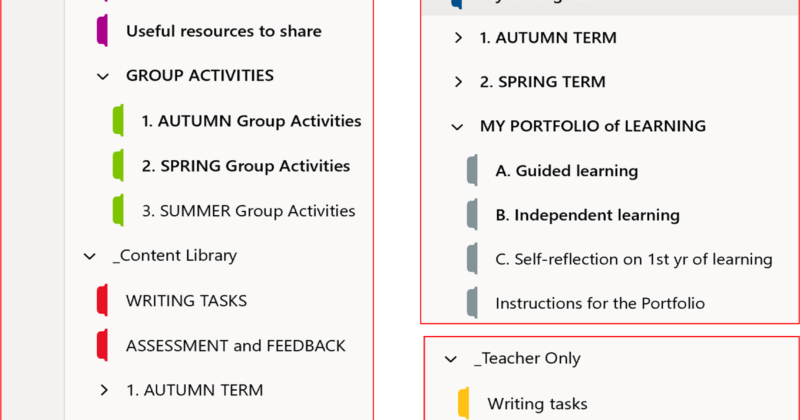

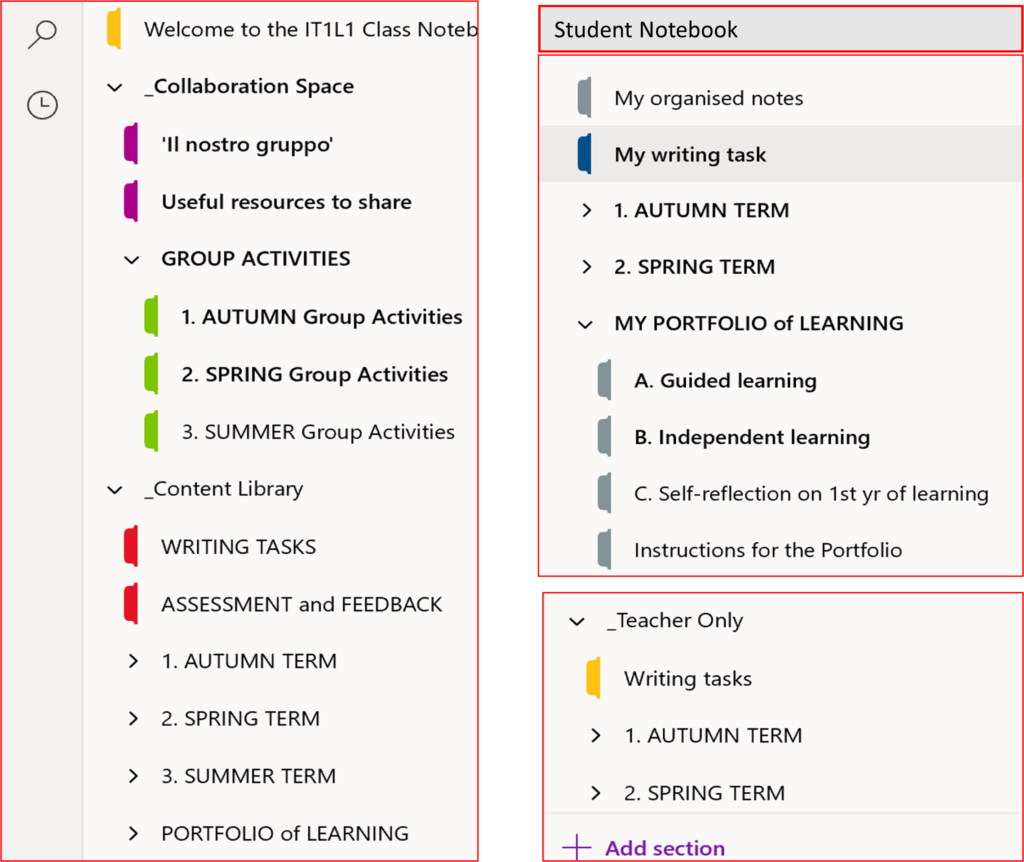

- Mapped key wellbeing themes to the stages of the programme. For example, a video and talk on ‘Managing the transition to HE: Balancing work and studies’ at the beginning of stage 1 (see Figure 1).

- Introduced wellbeing resources in the Professional Practice Module and reinforced content through ‘live’ talks, reflective activities and follow up tasks.

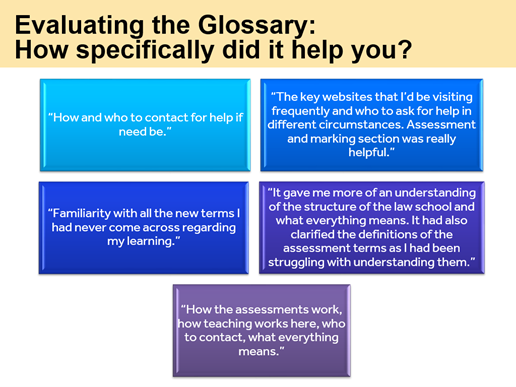

- Collected learner feedback and reviewed module evaluations to assess the impact and make iterative improvements to the resources.

Impact

The integration of tailored wellbeing resources into the programme had a positive and measurable impact on apprenticeship learners. Students reported feeling more supported in managing the dual demands of work and study, with increased confidence in applying wellbeing strategies such as stress reduction and maintaining motivation. We observed greater engagement and openness during reflective activities, indicating improved awareness and prioritisation of personal wellbeing. Employers also noted improvements in apprentices’ self-management, resilience, and motivation. Feedback highlighted the value of consistent, embedded support rather than one-off interventions, contributing to improved retention, progression, and alignment with Henley’s wellbeing-focused culture.

Reflections

The process of embedding tailored wellbeing resources into the programme was both rewarding and instructive. What worked particularly well was the collaborative, learner-informed approach. Engaging apprentices and employers in the development phase ensured the resources were relevant, practical, and sensitive to their dual roles. Embedding the materials within core modules rather than offering them as optional extras normalised wellbeing as an integral part of professional development.

However, some challenges emerged. Creating resources that were not only informative but also engaging proved challenging, given the authors inexperience with creating digital content. Interactive formats and the use of software helped but required significant time and creativity to develop effectively.

Overall, this ongoing initiative demonstrated the value of consistent, embedded wellbeing support. It fostered stronger connections between learners, tutors, and employers, and highlighted the importance of continued dialogue, flexibility, and cross-team collaboration in embedding a wellbeing-focused culture.