By: Dr Rachel Pye, School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, rachel.pye@reading.ac.uk

“For those who cannot work in groups, there is the danger of students either being required to do the work of several people, or do a completely different task, neither of which is an appropriate solution.”

Overview

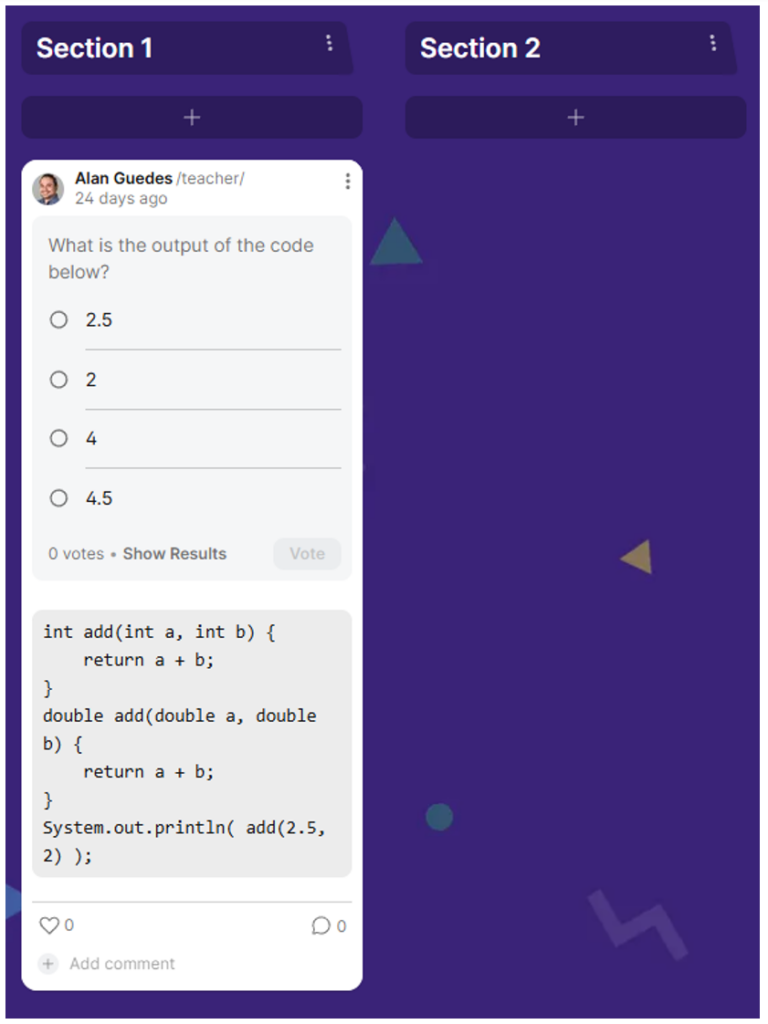

Altering ‘hands-on’ group-based assessment for those who can’t work in groups.

Context

Size of the cohort: 201-300

The School, Directorate, or Function: School of Psychology & Clinical Language Sciences

The Programme of study: Undergraduate taught

Applies to the following aspects of the student experience:

- coursework (research report)

- seminar environment

- style of presentation (by staff)

- group work

Context and implementation

It had been identified that in some compulsory modules, the project experience wasn’t as ‘hands-on’ as needed to appropriately scaffold students’ learning to enable them to approach their final capstone project with confidence in their data collection and management skills.

As a new module convenor, I led the redesign of a developmental psychology module’s project assessment, with the aim to provide practical experience in a common methodology when doing research with infants: video coding of infant behaviour. The development of a coding scheme and the collection of data lends itself well to group work, where the load can be shared. However, for those who cannot work in groups, there is the danger of students either being required to do the work of several people, or do a completely different task, neither of which is an appropriate solution.

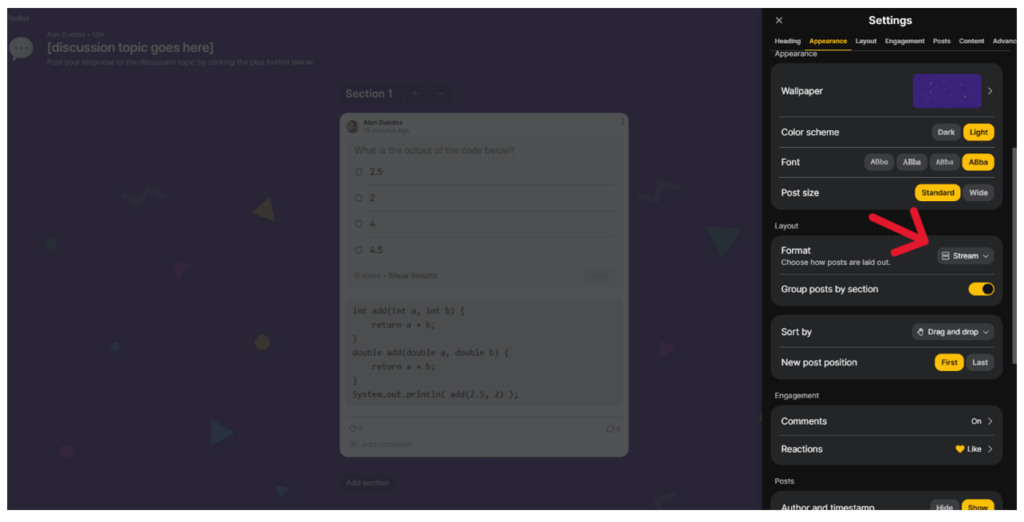

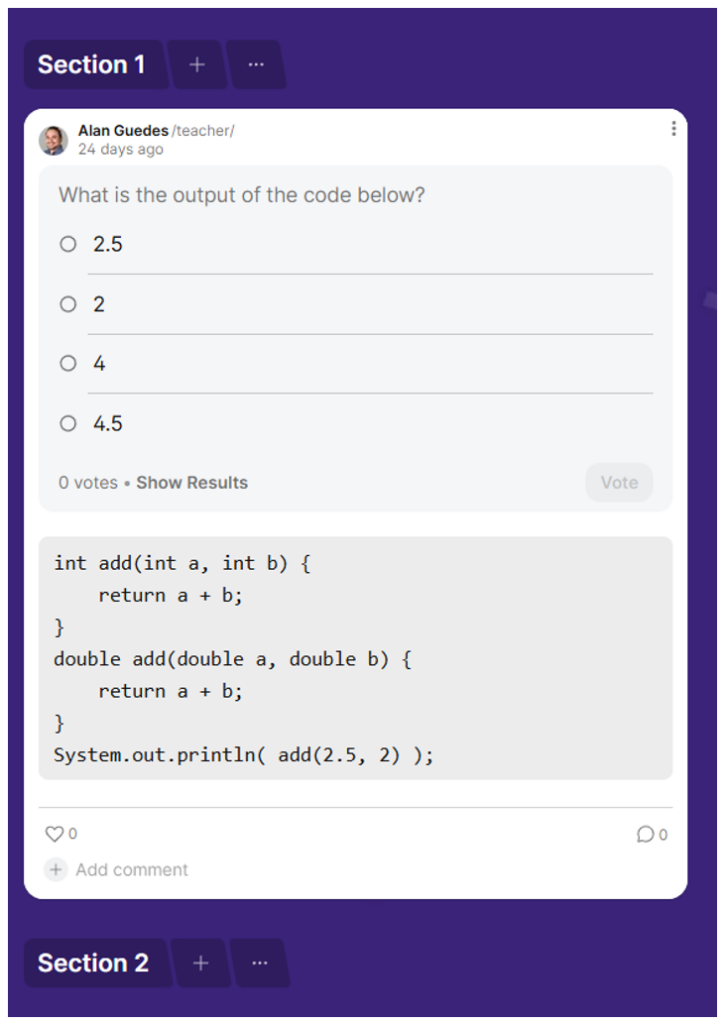

Therefore, I designed a version which enabled students to meet the learning outcomes, and acquire experience in these skills, by working alone on the project whilst still attending the same scheduled workshops as those working in groups. Those working alone created a coding scheme, but with fewer behaviours to be coded (around 50% of those working in groups), thus equalising the workload whilst enabling the same experience of coding real infant/parent interactions.

They also experienced calculating inter-rater reliability by comparing their own codes across time, rather than across different group members. We ensured that these students were appropriately supported throughout, and created a different online submission link so that the same member of staff could ensure the marking accounted for these slight differences in approach (this is a large cohort with a marking team of around 8 staff).

To support students who could work in groups but who struggled to initiate these, and following discussions with students on the different approaches, I allowed students to work with friends, or ask to be assigned to a group. This meant that those with an existing friendship group who were anxious weren’t randomly allocated to work with unknown peers, but those who preferred to do so were also supported. This process was managed vis MS Forms.

Impact

Students could work in the timetabled workshops, thus feeling part of the module community, benefitting from questions and support in class, whilst working individually. They could also choose not to attend workshops, as needed. They had the same experience of working with real experimental infant data, going through the same data collection steps as those working in groups. The feedback on the module overwhelmingly focussed on how well students felt supported through the process (though they found it challenging throughout).

For those who couldn’t attend sessions we provided a different assessment topic, so this approach did not remove the need for completely alternative assessments. However, by making this small adjustment to managing group work, we halved the number taking the formal alternative, which was by necessity a more paper-based assessment.

Reflective practice

I used student feedback through the formal university structures, discussed with individual student reps, and the formal module evaluation, to consider how to make the project assessment accessible and interesting for all students. Discussing the various options with students was useful in thinking through the barriers and possible solutions. This is a stressful assessment for many students, and I learned a lot about the importance of acknowledging their anxiety, and building their trust in me and themselves.

The students didn’t like this assessment, but the project and personal skills they develop through this process meant I was emphatic that we resisted the temptation to revert to the paper-based project, which is less challenging and less useful to their skills and knowledge development.

Advice for colleagues

It can be easy to step away from challenge when designing assessments, but students can only learn to trust themselves by being challenged and pushed outside their comfort zone. My main advice is to be honest about the challenge, but reassure students that you are there to support them, and explain why you have designed the assessment this way. By differentiating the challenge, all students learned they CAN do research, and students have confirmed that whilst they didn’t always appreciate it at the time, this experience supported their learning and preparation for the capstone project.

About the author

Rachel Pye is a lecturer, SDTL and module convenor in SPCLS. She convenes and teaches across developmental psychology modules in undergraduate psychology programmes. As an SDTL, Rachel supports staff who support and teach students across all the disciplines and levels in SPCLS.