By: Natalie Meek, School of Psychology & Clinical Language Sciences, n.a.meek@reading.ac.uk

Overview

Research within psychology has been largely conducted on a group that represent on 12% of the world’s population, those that are Western, educated, industrialised, rich and democratic (WEIRD) populations (Henrich et al., 2010). This colonial legacy, the centralising of the WEIRD population as representative of the human species, indicates a need to decolonise (Winter et al., 2022). The British Association for Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) who accredit our High Intensity Child, and Adult Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) programmes centre decolonisation and inclusion within their updated curriculum. In response to this, and decolonisation efforts elsewhere in the higher education sector, the aim of the BABCP is to embed EDI within assessment. Assessment is also a focus of this case study as assessment drives learning in higher education (Boud, 1995).

Objectives

- To change current assessment mark scheme to incorporate a section on EDI.

- To ensure assessment is in line with BABCP EDI guidance.

- To encourage student learning through assessment.

Context

The Charlie Waller Institute (CWI) offers graduate and post graduate clinical training courses. The training course discussed here is for High Intensity Adult CBT course, a year-long post-graduate clinical training course run twice a year with intakes of up to 50 students. The ongoing effort of the University to decolonise is essential within training courses to ensure our trainees are equipped to deliver equitable psychological support to all.

Implementation

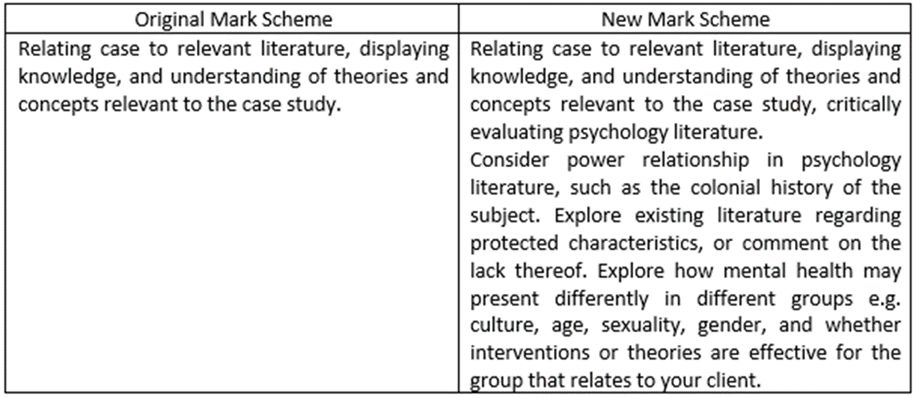

The extended case report (ERP) is an assessment used across two modules, a 5,000-word report which is set as part of paired assessment, was explored as a potential vehicle of change. There were some references to the identity of the client within the original mark scheme, however, little exploration of the client’s identity was required to pass the assessment. The High CBT Curriculum 4th Edition (NHS, 2022) states that trainees should be equipped with an understanding of EDI, and that we should support students to understand the needs of their clients in the context of protected characteristics. The curriculum (NHS, 2022) outlines the need for CBT therapists to achieve cultural competence, to be committed to anti-discriminatory clinical practice, and to have knowledge of research on CBT with minoritised groups. As assessment is an opportunity for learning (Sambell, et al., 2013), so this was a key opportunity to meet the BABCP curriculum.

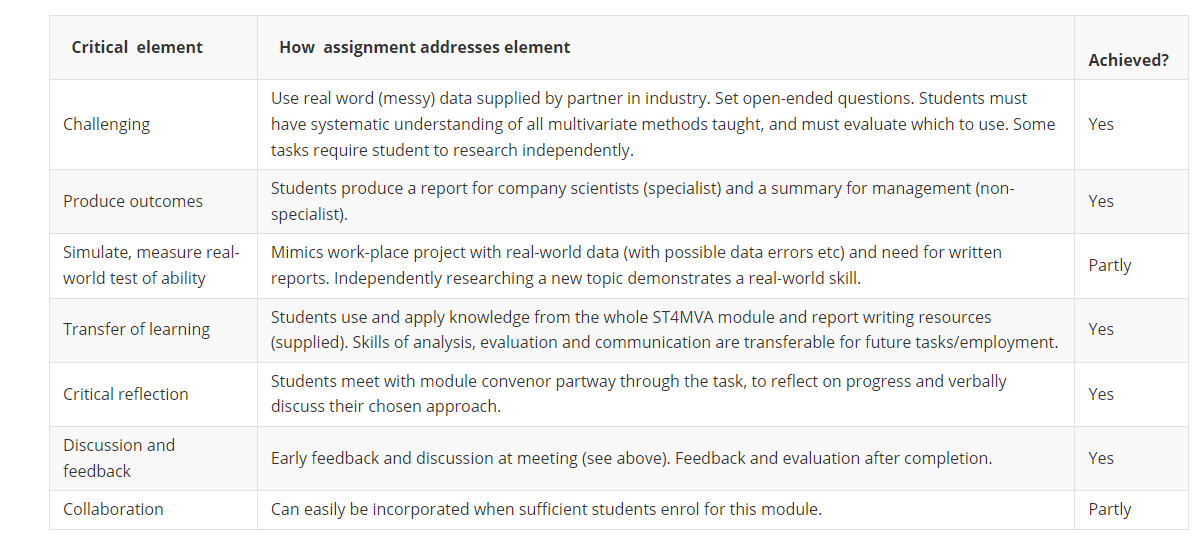

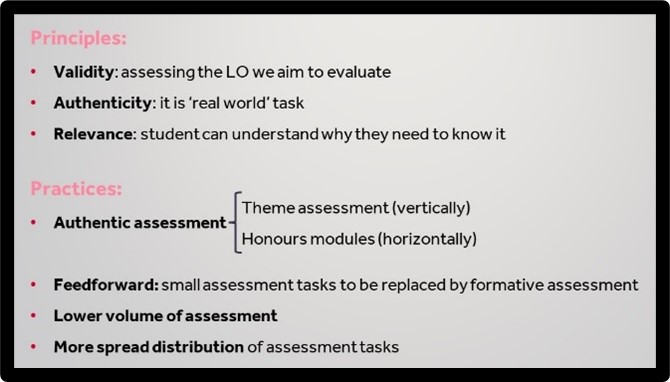

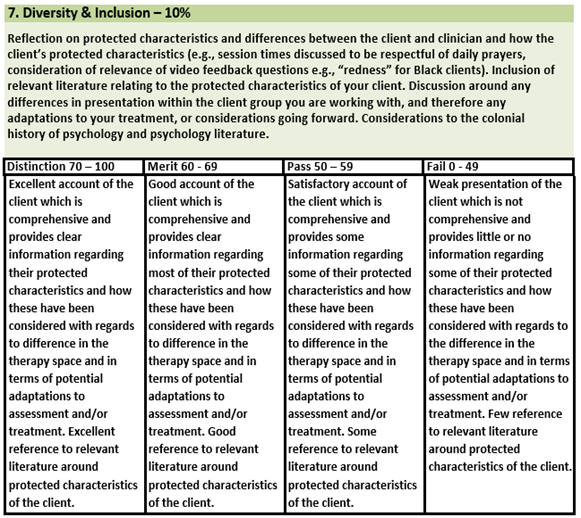

Historically assessment has been neglected in the process of decolonisation within higher education (Godsell, 2021) and this was the case within our course. Changes had been made to lectures, but no changes had been made in assessment. To ensure assessment was aligned with BABCP curriculum (NHS, 2022) and Minimum Training Standards (BABCP, 2022) the method of assessment was not able to be changed, so changes to the original mark scheme were made in two ways. The first was to change what constituted a passing mark for each section of the mark scheme, so that a lack of considerations of power relations in the literature, or protected characteristics would equate to a failing mark (Figure 1). The second change was to redefine item 6, originally Reflection, to Diversity & Inclusion, which is worth 10% of marks (Figure 2). To pass this section students must demonstrate a satisfactory account of protected characteristics (such as age, disability, gender, race, sex and religion) through an exploration of aspects of their client’s identity in CBT literature, and a reflection of their own identity. To support the students in this new aspect of assessment a lecture on “Identity & Values” so the topic was introduced prior to the assessment.

Impact

Student and marker feedback indicates the three objectives of this project have been met: the assessment and mark scheme incorporates EDI, the changes are in line with BABCP guidance for EDI, and these changes have facilitated student learning. The changes to the mark scheme were rolled out for two modules of the HI CBT Adult course and adopted by the HI CBT Childrens course also. Feedback from markers indicate a noticeable increase in the student’s consideration of the client’s identity, and a diversification of CBT literature utilised for reports. In the Theory and Practice for Depression (PYMDEP) module evaluation, students’ ratings of “course content/examples/case studies selected (or used) offer a diversity perspective” has increased from an average of 3.5 to 4.4, where 5 means definitely agree. Although this feedback is not solely regarding changes to assessment, it does indicate change has been recognised and is having a positive impact.

Reflections

Decolonisation, and developing cultural competence are both ongoing processes, which require lifelong learning. This change in assessment has been one step in meeting BABCP curriculum guidance (NHS, 2022) and in training our therapy workforce to deliver anti-discriminatory, and effective therapy for diverse groups of people. This change has happened in line with lecture content changes, such as the introduction of teaching day on working with neurodivergence, gender & sexuality, and religion & spirituality.

Follow up

One change within an assessment does not end the ongoing process of decolonisation and of the integration of EDI within higher education. Going forward it would be good to get more feedback directly from students’ assessment, and any further work we can do to continue to decolonise the course and ensure all peoples can access equitable psychological support.

References

- BABCP (2022). Minimum Training Standards. https://babcp.com/Portals/0/Files/About/ Minimum%20Training%20Standards%201222.pdf?ver=2022-12-15-155902-380

- Boud, D. (1995). Assessment and learning: contradictory or complementary. Assessment for Learning in Higher Education, 35–48.

- Godsell, S. D. (2021). Decolonisation of history assessment: An exploration. South African Journal of Higher Education, 35(6), 101–120.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 61–83.

- NHS (2022). National Curriculum for High Intensity Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Courses (4th ed.). https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/HiT%20Curriculum%20%28name%20of%20document%20on%20HEE%20website%20says%20PWP%20Curriculum%204th%20Edition%202022_10%20Nov%202022%29.pdf

- Sambell, K. (2013). Engaging students through assessment. The student engagement handbook: Practice in Higher Education (pp. 379–396). Emerald.

- Winter, J., Webb, O., & Turner, R. (2024). Decolonising the curriculum: A survey of current practice in a modern UK university. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 61(1), 181–192.