By: Dr Laura Girling, Agriculture, Policy and Development, Laura.Girling@reading.ac.uk

Overview

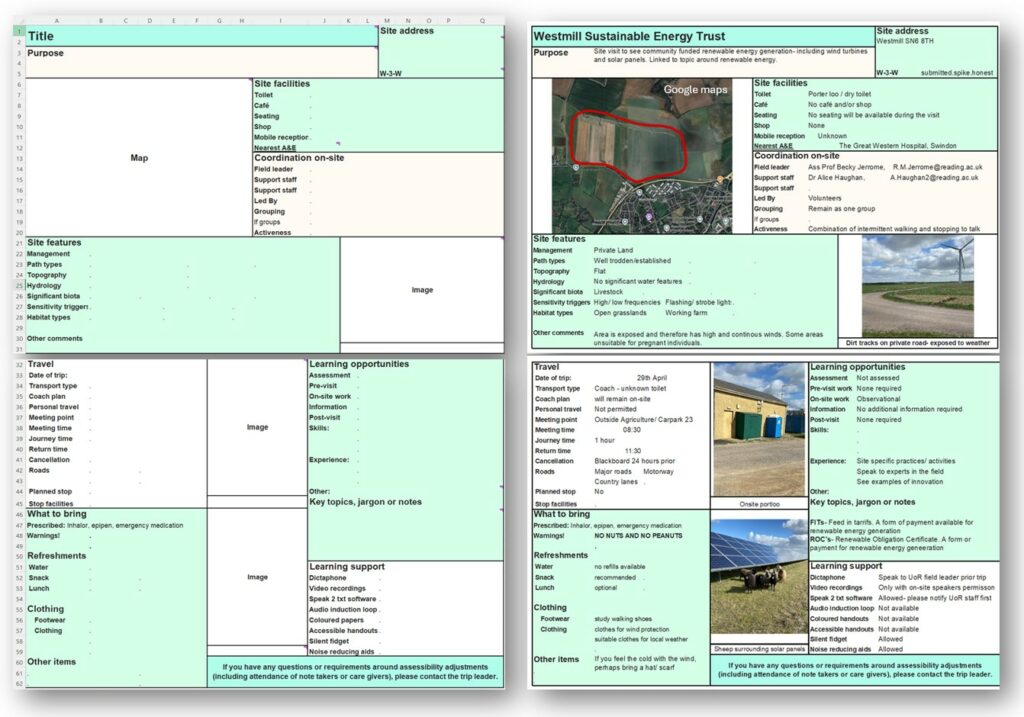

Funded through the T&L Initiative Fund, we co-designed a user-friendly template that allows staff to generate clear and relevant fieldtrip information leaflets. Whilst the focus was to better support Students with Accessibility Needs (SAN), the products tested also held benefits for the wider student cohort and enables students to make more informed choices about field trip attendance and maximise their learning opportunity.

Objectives

To develop a template for staff to use to optimise the learning value of fieldtrips by:

- Enhancing quality and clarity of field-trip information to maximise the student experience and learning opportunities.

- Supporting SAN through in-built leaflet design, presentation and inclusion of specialist content. For example, details of important on-site facilities, identification of additional support available/ allowed, and use of British Dyslexia Association (BDA) recommended font type, size and spacing.

- Incorporating staff considerations into the template design to ensure practicality and ease of use.

Context

Student absence from fieldtrips leads to unnecessary costs, missed learning opportunities and sometimes requires alternative assessments. Pre-fieldtrip information currently varies widely between staff, which may leave students failing to recognise the trip’s value or leave them feeling unprepared, uncertain or anxious. Research literature also claims prior information can support student capacity to learn and reduce anxiety (Haynes et al.,2005: Tucker et al.,2022).

Implementation

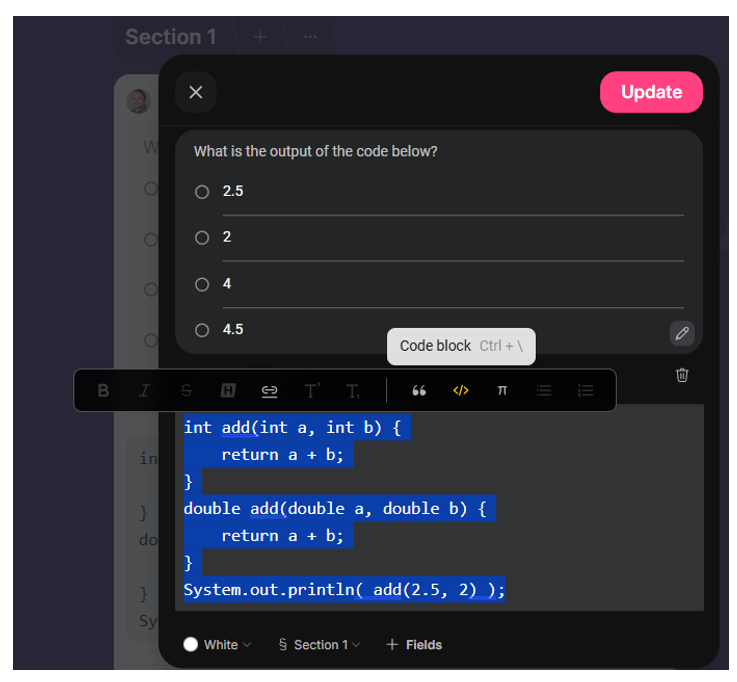

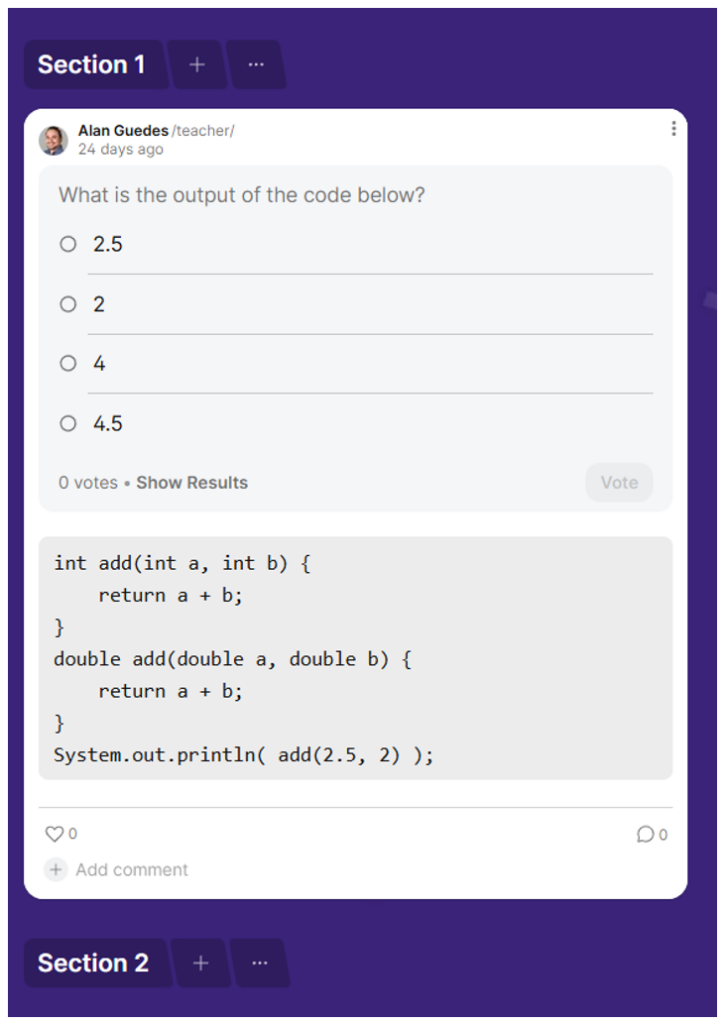

We undertook an iterative approach to co-designing a template for fieldtrip leaflets, engaging with a range of stakeholders and incorporating research literature. Design aspects around formatting and style were informed by BDA (2014) guidelines (2014).

Project students jointly defined our use of the term Student with Accessibility Needs’ (SAN) and identified these learners to be our priority focus for the work. These SAN learners included students facing physical, mental and/or learning difficulties. Project students identified key content including a specific section on learning support, details about onsite grouping, keywords and acronyms likely to be used onsite, identification of sensory triggers, and also ensured the wording of the leaflet was student friendly.

Staff piloted populating the template and fed comments back to the project team. Colleagues noted the section on making learning support explicit was valuable, as they had previously just assumed students would reach out if they needed additional support.

Two pilot leaflets were trialled with students and evaluated through an online survey with Likert-style questions. Results were analysed with project students, interpretations discussed and learning fed back into the template.

Impact

Improved ‘student organisation’ was the largest benefit for non-SAN learners, and for SAN individuals, it was ‘being mentally prepared’. Sixty-five per cent of students reported an “improved experience”, and 88% wanted staff to use leaflets on some or all fieldtrips.

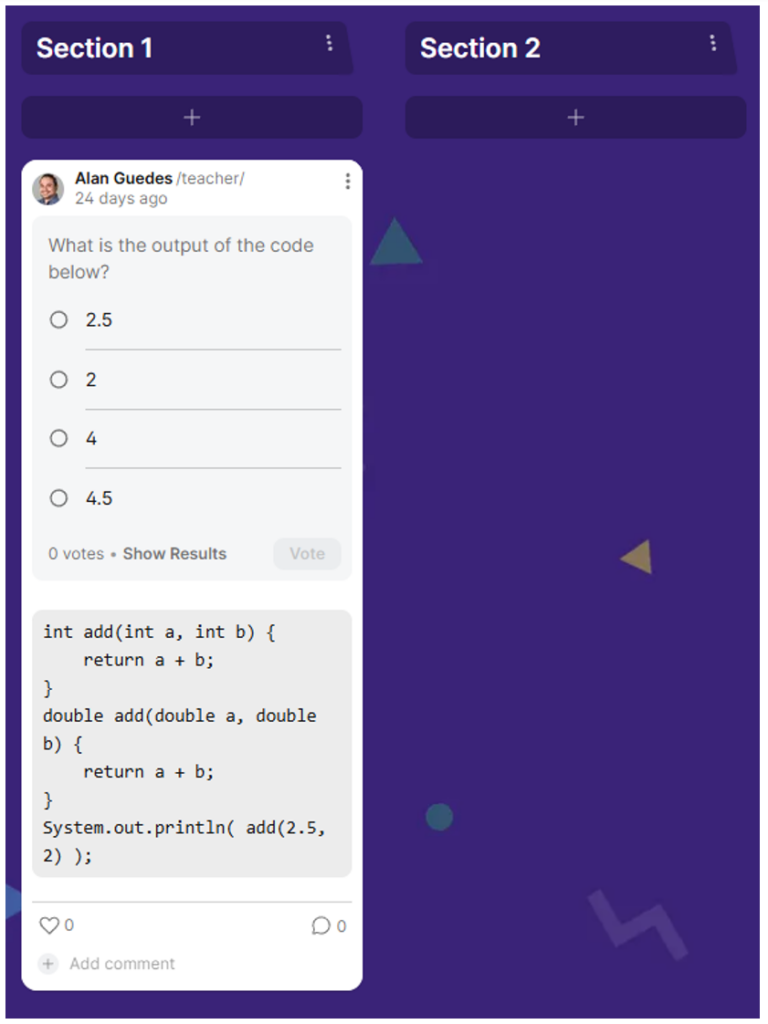

The template has been used on more than four fieldtrips (see figure 1 for an example), has been presented at the 2024 Enhancing Fieldwork Learning Conference in Edinburgh, and the template shared with external individuals. In modules where fieldtrips are linked to assessment, we anticipate students will use the leaflets for information and as visual reminders.

The project has raised awareness in the school around accessibility, encouraging colleagues to view the environment in a different way and recognising more of the challenges some students may face.

A particularly eye-opening theme in the comments from project students concerned the need for time to unwind, re-energise, or clean up after field trips, either due to transition fatigue or sensory overstimulation. In response, fieldtrip timetabling has been extended by an hour to ensure students are not late for their next lecture, which can cause anxiety, and have space to decompress before refocusing on remaining lectures.

Reflections

I am proud to see how this project empowered the project-students to share their experiences openly. Their reflections highlighted that students may be afraid or embarrassed to speak out about their needs, and as a result, choose not to attend field trips. Hopefully, the increase of information and the action implied by the leaflet, to better support students, will initiates more conversations between students and lecturers.

Sourcing images was the most time intensive element of creating the leaflet, and images illustrating accessibility features were either difficult to find, or just unavailable. This may result in staff undertaking greater reflection during field-site visits when they are trying to identify appropriate images to take. Because fieldtrips often run annually, investing the time to capture clear, informative images and material will benefit students and staff in future years.

The alternative ideas the students generated through the project were both simple and addressed directly their barriers and concerns. These were shared after the ‘leaflet’ approach was adopted and suggests that if the project had initially started with a blank ‘canvas’, the output may have been different.

It is exciting that this project may benefit for not only SAN but also may address some of the broader engagement concerns around poor student organisation and in students not recognising the value in attending.

Follow up

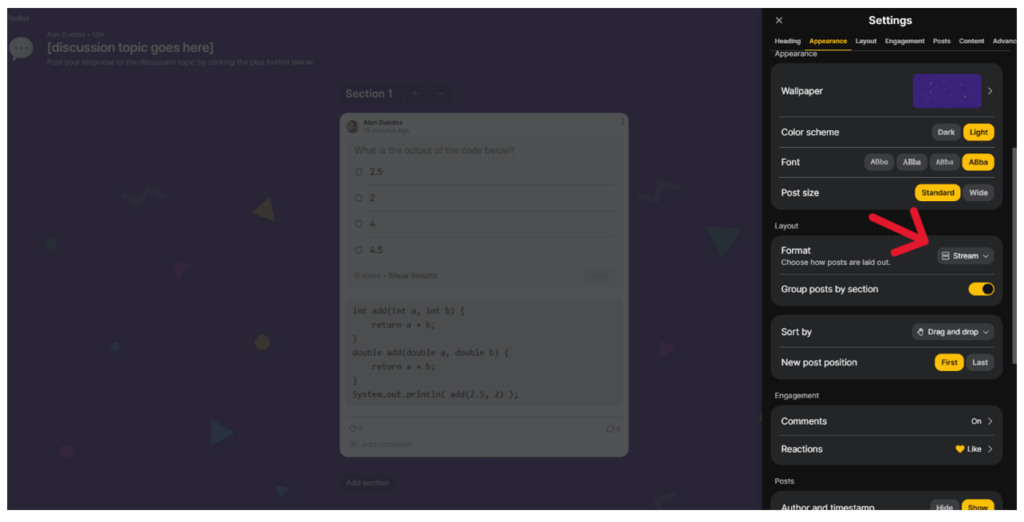

The most challenging part of this project was identifying a user-friendly platform suitable for the template. Currently, Excel is used, but this is inefficient and threatens the longevity of the work.

Revisiting some of the students’ alternative ideas for improving accessibility would be beneficial, as is continuing to gather user experience from staff and students.

References & further reading

- BDA. (2014). BDA Dyslexia Style Guide. https://www.thedyslexia-spldtrust.org.uk/media/downloads/69-bda-style-guide-april14.pdf

- Haynes, C., Pieper, J. C., & Trexler, C. (2005). A comparison of pre-visits for youth field trips to public gardens. HortTechnology 15(3), 458-462 https://10.21273/HORTTECH.15.3.0458

- Tucker, F., Waite, C., & Horton, J. (2022). Not just muddy and not always gleeful? Thinking about the physicality of fieldwork, mental health, and marginality. Area 54(4) pp. 563-568. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12836