Dr Maria Kambouri-Danos, Institute of Education m.kambouridanos@reading.ac.uk Year of activity 2017/18

Overview

I recently led a group of colleagues while working in partnership with students to develop a new module in BA in Children’s Development and Learning (BACDL) delivered at the Institute of Education (IoE). This approach to working in partnership with students is a core part of the project’s aim and the work described here has been part of a Partnerships in Learning & Teaching (PLanT) project.

Objective

The team’s aim was to develop and finalise a new module for BACDL in close partnership with the students. The new module will replace two existing modules (starting from 2018-19), aiming to reduce overall assessment (programme level), a need identified during a Curriculum Review Exercise. The objective was to adopt an inclusive approach to student engagement when finalising the new module, aiming to:

- Go beyond feedback and engage students by listening to the ‘student voice’

- Co-develop effective and student-friendly assessable outcomes

- Identify opportunities for ‘assessment for learning’

- Think about constructive alignment within the module

- Encourage the development of student-staff partnerships

Context

To accomplish the above, I brought together five academics and six students (BACDL as well as Foundation Degree (FDCDL) students). Most of the students on this programme are mature students (i.e. with dependants) who are working full time while attending University (1 day/week). To encourage students from this ‘hard to reach group’ to engage with the activity, we secured funding through the Partnerships in Learning & Teaching scheme, which enabled the engagement of a more diverse group (Trowler, 2010).

Implementation

The team participated in four partnership workshops, during which staff and students engaged in activities and discussions that helped to develop and finalise the new module. During the first workshop, we discussed the aims of the collaborative work and went through the module’s summary, aims and assessable outcomes. We looked at the two pre-existing modules and explored merging them into a new module, maintaining key content and elements of quality. During the second workshop, we explored chapter two from the book ‘Developing Effective Assessment in Higher Education: a practical guide’ (Bloxham & Boyd, 2007), which guided the discussions around developing the assessment design for the new module.

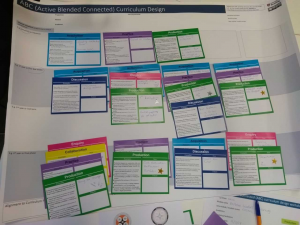

During the third workshop, we discussed aspects of summative and formative tasks and finalised the assessment design (Knight, 2012). We then shared the new module description with the whole BACDL cohort and requested feedback, which enabled us to get other students’ views, ensuring a diverse contribution of views and ideas (Kuh, 2007). During the last workshop, with support from the Centre of Quality Support and Development (CQSD) team, we implemented a game format workshop and created a visual ‘storyboard’, outlining the type and sequence of learning activities required to meet the module’s learning outcomes (ABC-workshop http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/abc-ld/home/abc-workshop-resources/). This helped to identify and evaluate how the new module links with the rest of the modules, while it also helped to think about practical aspects of delivering the module and ways to better support the students (e.g. through a virtual learning environment).

Photos from staff-student partnership workshops

Impact

The close collaboration within the team ensured that the student voice was heard and taken into account while developing the new module. The partnership workshops provided the time to think collaboratively about constructive alignment and ensure that the new module’s assessment enables students to learn. It also ensured that the module’s assessable outcomes are clearly defined using student-friendly language.

A pre- and post-workshop survey was used to evaluate the impact of this work. The survey measured the degree to which students appreciate the importance of providing feedback, participate in activities related to curriculum review/design, feel part of a staff-student community and feel included in developing their programme. The survey results indicate an increase in relation to all of the above, demonstrating the positive impact of activities like this on student experience. All students agreed that it has been beneficial to take part in this collaborative work, mentioning that being engaged in the process, either directly (attending the workshops) or indirectly (providing feedback) helped them to develop a sense of belonging and feel part of the community of staff and students working together (Trowle, 2010; Kuh, 2005;2007).

Reflections

This project supported the successful development of the new module, from which future students will benefit (Kuh, 2005). The work that the team produced has also informed the work of other groups within the IoE. At the institutional level, this work has supported the development of the CQSD ‘Student Engagement’ projects. All the above were achieved because of close collaboration, and could not have been done by a group of individuals working on their own (Wheatley, 2010). Because of that, our team was awarded the University Collaborative Awards for Outstanding Contributions to Teaching and Learning.

References

Bloxham, S. & Boyd, P. (2007). Developing effective assessment in higher education: a practical guide. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Knight, P. (Ed.). (2012). Assessment for learning in higher education. Routledge.

Kuh, G.D. (2005). Putting Student Engagement Results to Use: Lessons from the Field, Assessment Update. 17(1), 12–1.

Kuh, G.D. (2007). How to Help Students Achieve, Chronicle of Higher Education. 53(41), 12–13.

Trowler, V. (2010). Student engagement literature review. The Higher Education Academy.

Wheatley, M. (2010). Finding our Way: Leadership for an Uncertain Time. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler

During the summer of 2016 we applied for £300 from the funds of Teaching and Learning Dean Dr David Carter and were awarded the full amount. We were keen to develop our professional development scheme for students in the School of Literature and Languages, the Professional Track, and we needed some external, professional input in order to do this.

During the summer of 2016 we applied for £300 from the funds of Teaching and Learning Dean Dr David Carter and were awarded the full amount. We were keen to develop our professional development scheme for students in the School of Literature and Languages, the Professional Track, and we needed some external, professional input in order to do this. Research Placement Project (LW2RPP) is a module developed within the School of Law that aims to provide Part Two students with a hands-on experience of the academic research process, from the design of a project and research question through to the production of a research output. It is an optional module that combines individual student research, lectures and seminars.

Research Placement Project (LW2RPP) is a module developed within the School of Law that aims to provide Part Two students with a hands-on experience of the academic research process, from the design of a project and research question through to the production of a research output. It is an optional module that combines individual student research, lectures and seminars. In a Part Two Law module, Public Law (LW2PL2), we have moved away from the conventional exam to a take-home exam. We publish the exam paper on Blackboard at an arranged date and time. We give the students approximately 48 hours to complete and submit their answers electronically.

In a Part Two Law module, Public Law (LW2PL2), we have moved away from the conventional exam to a take-home exam. We publish the exam paper on Blackboard at an arranged date and time. We give the students approximately 48 hours to complete and submit their answers electronically.