Tamara Wiehe, Charlotte Allard & Hayley Scott (PWP Clinical Educators)

Charlie Waller Institute; School of Psychology and Clinical Language

Overview

In line with the University’s transition to Electronic Management of Assessment (EMA), we set out to create an electronic Portfolio (e-Portfolio) for use on our Psychological Well-being Practitioner (PWP) training programmes to replace an existing hard-copy format. The project spanned almost 1 year (October 2018- September 2019) as we took the time to consider the implications on students, supervisors in our IAPT NHS services, University administrators and markers. Working closely with the Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) team led us to a viable solution that has been launched with our new cohorts from September 2019.

Objectives

- Create an electronic Portfolio in line with EMA that overcomes existing issues and improves the experience for students, NHS supervisors, administrators and markers.

- Work collaboratively with our all key stakeholders to ensure that the new format satisfies their various needs.

Context

A national requirement for PWPs is to complete a competency-based assessment in the form of a Portfolio that spans across their three modules of their training. Our students are employed by NHS services across the South of England and many live close to their service rather than the University.

The issue? The previous hard-copy format meant that students spent time and money printing their work and travelling to the University to submit/re-submit it. University administrators and markers reported issues with transporting the folders to markers and storing them, especially with the larger cohorts.

The solution… To resolve these issues by transitioning to an electronic version of the Portfolio.

Implementation

- October 2018: An initial meeting with TEL was held in order to discuss the practicalities of an online Portfolio submission.

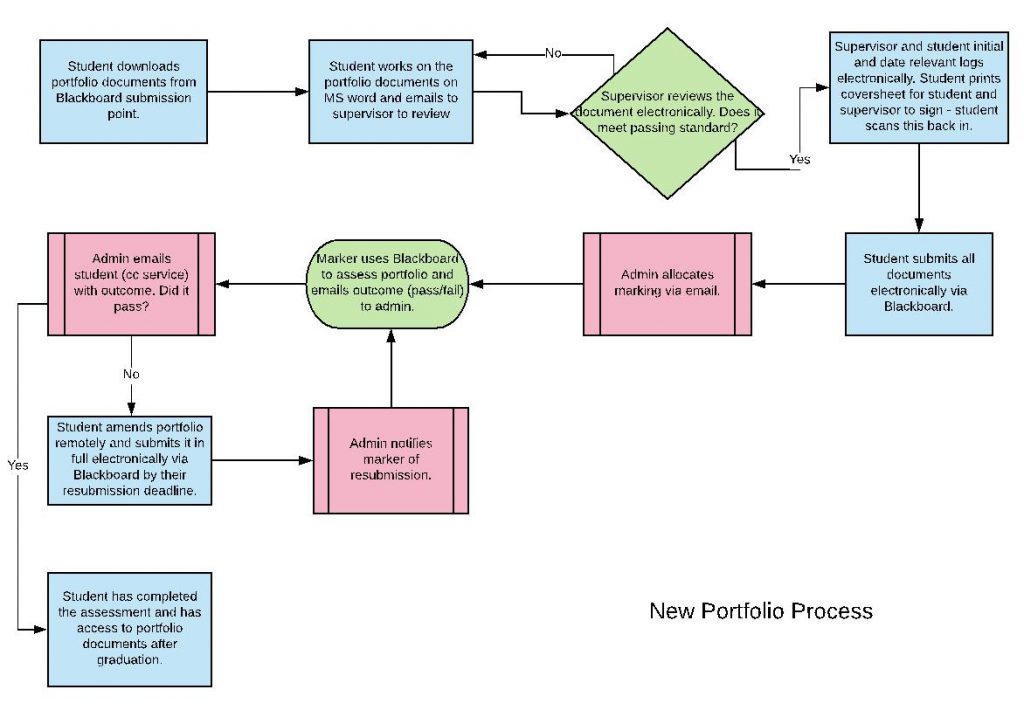

- October 2018 – March 2019: TEL created several prototypes of options for submission via Blackboard including the use of the journal tool and a zip file. Due to practicalities, the course team decided on a single-file word document template.

- April – May 2019: Student focus groups were conducted with both programmes (undergraduate and postgraduate) where the same assessment sits to gain their feedback with the potential solution we had created. Using the outcomes of the focus groups and staff meetings, it was unanimously agreed that the proposed solution was a viable option for use with our future cohorts.

- June 2019: TEL delivered a training session for staff and admin to become familiar with the process from both student and staff perspective. TEL also created a guidance document for administrators on how to set up the assignment on Blackboard.

- July – August 2019: Materials including the template and rubrics were amended and formatted in order to meet requirements for online submission for both MSci and PWP courses. Resources were also created for students to access on Blackboard such as screen casts on how to access, utilise and submit the Portfolio using the electronic format; the aim of this is to improve accessibility for all students participating on the course.

- September 2019: Our IAPT services were notified of the changes as the supervisors there are responsible for reviewing and ‘signing off’ on the student’s performance before the Portfolio is submitted to the University for a final check.

Impact

Thus far, the project has achieved the objectives it set out to. The template for submission is now available for students to complete throughout their training course. This will modernise the submission process and be less burdensome for the students, supervisors, administrators and markers.

The students in the focus group reported that this would significantly simplify the process and relieve the barriers they often reported with completing and submitting the Portfolio. Currently, there have not been any unexpected outcomes with the development of the Portfolio. However, we aim to review the process with the first online Portfolio submission in June 2020.

Reflections

Upon reflection, the development of the online Portfolio has so far been a success. Following student feedback, we listened to what would improve their experience of completing the Portfolio. From this we developed an online Portfolio, meeting the requirements across two BPS accredited courses which will be used for future cohorts of students.

Additionally, the collaboration between staff, students and the TEL team, has led to improved communication across teams with new ideas shared; this is something we have continued to incorporate into our teaching and learning projects.

An area to develop for the future, would be to utilise a specific Portfolio software. Initially, we wanted to use a journal tool on Blackboard, however, it was not suitable to meet the needs of the course (most notably exporting the submission and mark sheet to external parties). We will continue to review these options and will continue to gain feedback from future cohorts.