By: Victoria Grace-Bland and Michael Kilmister, Academic Development and Enhancement (CQSD-ADE), v.grace-bland@reading.ac.uk

Overview

Zines (pronounced ‘zeens,’ as in magazines) are small, handmade artbooks or magazines that allow the maker to freely express themselves and share their art, words, and thoughts in a fun and creative way. We facilitated a staff-focused zine-making workshop during Wellbeing Week (February 2025) which was attended by 13 academic and professional staff (including us). The session built belonging, created a community of like-minded practitioners interested in creative and wellbeing focused pedagogies, and was a low-risk way of encouraging colleagues to give zine making a go. It is a springboard for future creative pedagogy-focused activities.

Objectives

As University of Central Lancashire’s ‘MadZines’ research shows, mental health and wellbeing practice can be understood and disseminated through zine-making practices. This is particularly relevant in our context – in May 2025, the University’s work to enhance student wellbeing was recognised by the award of Student Minds’ University Mental Health Charter Award.

Zine-making sessions are inclusive communal spaces where participants can freely explore ideas and materials through crafting exercises in a group environment. These spaces exist outside the formal confines of the classroom, reducing hierarchies, encouraging authentic expression of ‘the self’, and fostering collaborative exploration of ideas. Furthermore, the authentic and varied perspectives captured through zine making can inform initiatives and discussions about wellbeing and University experiences.

Context

As made clear by the University’s Wellbeing website, Reading ‘has a strong commitment to employee health and wellbeing.’ To help support this commitment, for the past few years staff have volunteered their time to organise and run activity sessions during Wellbeing Week. For Wellbeing Week 2025 (24th–28th February), colleagues gave up their time to share their skill or passion with others. Sessions ranged from board games and origami to walks and tap dancing.

For the second year in a row, we organised a zine-making workshop for staff titled ‘Zine Your Way to Zen.’ We co-facilitated the event with International Student Experience Manager Corinne Brookes.

“zine making is an inclusive practice for neurodivergent colleagues, enabling them to engage in a safe space.”

Implementation

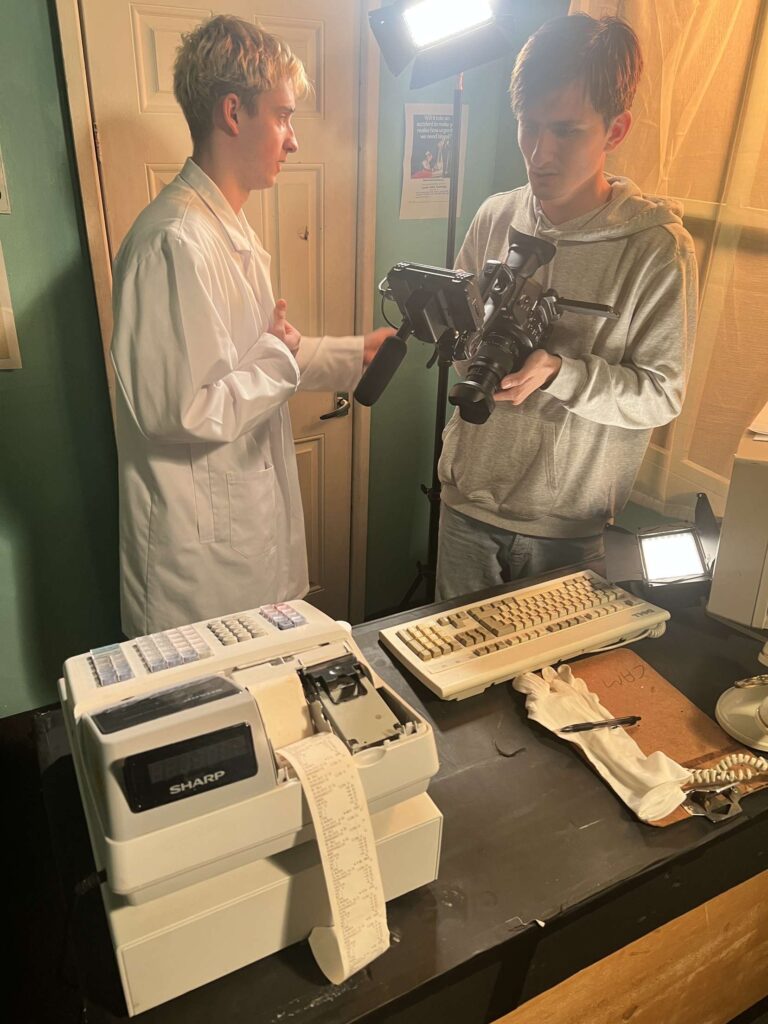

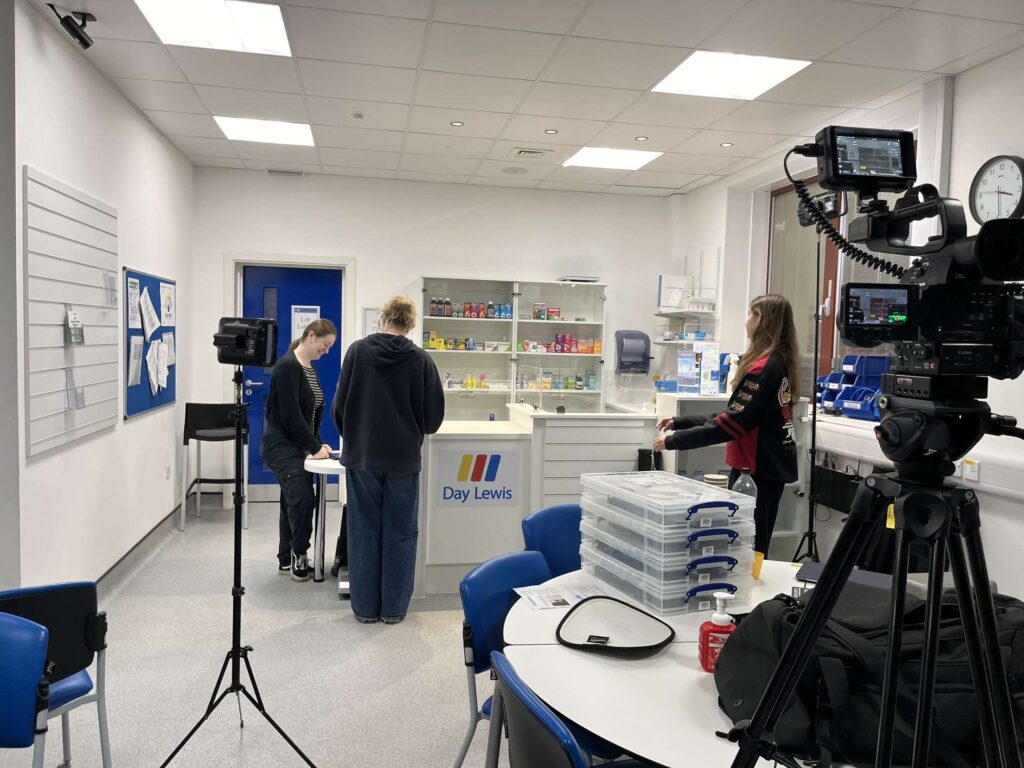

The zine-making workshop took place in the Meadow Suite, surrounded by colleagues involved in Wellbeing Week activities. The workshop was relaxed and provided a space for staff to drop in and begin to play with materials and create visual works around the theme of wellbeing. After demonstrating a simple zine folding exercise, the facilitators encouraged the participants to flick through example zines and explore the materials available (glue, pens, papers, recycled magazines, newspapers, cards, old university marketing collateral) (Figure 1). Participants had free creative control over how they approached their zines, and how they wanted to represent their individual ideas and wellbeing concepts through collaging recycled materials, drawing, and creative writing.

Impact

With wellbeing as the central focus of this activity, we were keen to find out how colleagues were feeling at the end of the zine-making session and whether attending had any impact on their mood. Colleagues told us that the time spent crafting and creating their zines had left them feeling ‘inspired’, ‘comfortable’ and ‘focussed’.

Colleagues also commented on how the session impacted on their sense of belonging to the university beyond their own department, for example one colleague told us the felt “part of a community – it was lovely to speak to other people and see their ideas. I also felt proud of what I created.” One colleague later remarked to us that “zine making is an inclusive practice for neurodivergent colleagues, enabling them to engage in a safe space.”

Reflections

Being part of something that goes beyond your departmental boundaries is a great way to find connection, build networks and push yourself out of embedded patterns and comfort zones within the workplace. Taking time away from the day-to-day requirements of your role can help to refocus and refresh your outlook on the workplace. Colleagues at the zine-making workshops informally discussed the benefits of building on opportunities such as these, including future creative activities and chances to work collaboratively.

Follow up

The workshop has acted as a springboard for further zine-making activities and continues to provide opportunities for collaborative practice across departments and services. Some participants expressed interest in joining an emerging community of practice centred on creative and/or playful approaches to learning and wellbeing, which is currently in development for the 2025-26 academic year. We continue to run zine-making workshops on the theme of sustainability, which is integral to wellbeing.

If you’re interested in getting involved in the future, please visit the zines page on the CQSD website.

Further reading

- See more case studies on the CQSD website: https://sites.reading.ac.uk/curriculum-framework/zines/