Dr Bolanle Adebola is the Module Convenor and lecturer for the following modules on the LLM Programme (On campus and distance learning):

International Commercial Arbitration, Corporate Governance, and Corporate Finance. She is also a Lecturer for the LLB Research Placement Project.

Bolanle is also the Legal Practice Liaison Officer for the CCLFR.

OBJECTIVES

For students:

• To make the assessment criteria more transparent and understandable.

• To improve assessment output and essay writing skills generally.

For the teacher:

• To facilitate assessment grading by setting clearly defined criteria.

• To facilitate the feedback process by creating a framework for dialogue which is understood both by the teacher and the student.

CONTEXT

I faced a number of challenges in relation to the assessment process in my first year as a lecturer:

• My students had not performed as well as I would have liked them to in their assessments.

• It was my first time of having to justify the grades I had awarded and I found that I struggled to articulate clearly and consistently the reasons for some of the grades I had awarded.

• I had been newly introduced to the step-marking framework for distinction grades as well as the requirement to make full use of the grading scale which I found challenging in view of the quality of some of the essays I had graded.

I spoke to several colleagues but came to understand that there were as many approaches as there were people. I also discussed the assessment process with several of my students and came to understand that many were both unsure and unclear about the criteria by which their assessments were graded across their modules.

I concluded that I needed to build a bridge between my approach to assessment grading and my students’ understanding of the assessment criteria. Ideally, the chosen method would facilitate consistency and the provision of feedback on my part, and improve the quality of essays on my students’ part.

IMPLEMENTATION

I tend towards the constructivist approach to learning which means that I structure my activities towards promoting student-led learning. For summative assessments, my students are required to demonstrate their understanding and ability to critically appraise legal concepts that I have chosen from our sessions in class. Hence, the main output for all summative assessments on my modules is an essay. Wolf and Stevens (2007) assert that learning is best achieved where all the participants in the process are clear about the criteria for the performance and the levels at which it will be assessed. My goal therefore became to ensure that my students understood the elements I looked for in their essays; these being the criteria against which I graded the essays. They also had to understand how I decided the standards that their essays reflected. While the student handbook sets out the various standards that we apply in the University, I wanted to provide clearer direction on how they could meet or how I determine that an essay meets any of those standards.

If the students were to understand the criteria I apply when grading their essays, then I would have to articulate them. Articulating the criteria for a well-written essay would benefit both myself and my students. For my students, in addition to a clearer understanding of the assessment criteria, it would enable them to self-evaluate which would improve the quality of their output. Improved quality would lead to improved grades and I could give effect to university policy. Articulating the criteria would benefit me because it would facilitate consistency. It would also enable me to give detailed and helpful feedback to students on the strengths and weaknesses of the essays being graded, as well as on their essay writing skills in general; with advice on how to improve different facets of their outputs going forward. Ultimately, my students would learn valuable skills which they could apply across board and after they graduate.

For assessments which require some form of performance, essays being an example, a rubric is an excellent evaluation tool because it fulfils all the requirements I have expressed above. (Brookhart, 2013). Hence, I decided to present my grading criteria and standards in the form of a rubric.

The rubric is divided into 5 criteria which are set out in 5 rows:

- Structure

- Clarity

- Research

- Argument

- Scholarship.

For each criterion, there are 4 performance levels which are set out in columns: Poor, Good, Merit and Excellent. An essay will be mapped along each row and column. The final marks will depend on how the student has performed on each criterion, as well as my perception of the output as a whole.

Studies suggest that a rubric is most effective when produced in collaboration with the students. (Andrade, Du and Mycek, 2010). When I created my rubric, I did not involve my students, however. I thought that would not be necessary given that my rubric was to be applied generally and with changing cohorts of students. Notwithstanding, I wanted students to engage with it. So, the document containing the rubric has an introduction addressed to the students, which explains the context in which the rubric has beencreated. It also explains how the rubric is applied and the relationship between the criteria. It states for example, that ‘even where the essay has good arguments, poor structure may undermine its score’. It explains that the final grade combines but objective assessment and a subjective evaluation of the output as a whole which is based on the marker’s discretion.

To ensure that students are not confused about the standards set out in the rubric and the assessment standards set out in the students’ handbook, the performance levels set out in the rubric are mapped against the assessment standards set out in the student handbook. The document containing the rubric also contains links to the relevant handbook. Finally, the rubric gives the students an example of how it would be applied to an assessment. Thereafter, it sets out the manner in which feedback would be presented to the students. That helps me create a structure in which feedback would be provided and which both the students and I would understand clearly.

IMPACT

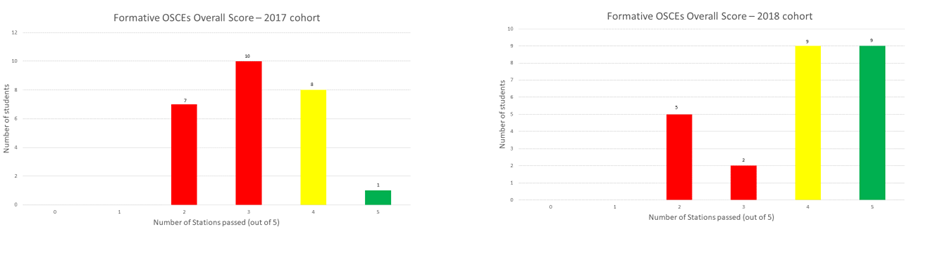

My students’ assessment outputs have been of much better quality and so have achieved better grades since I introduced the rubric. In one of my modules, the average grade, as recorded in the module convenor’s report to the external examiner (MC’s Report), 2015/16, was 64.3%. 20% of the class attained distinctions, all in the 70-79 range. That year, I struggled to give feedback and was asked to provide additional feedback comments to a few students. In 2016/17, after I introduced the rubric, there was a slight dip in the average mark to 63.7%. The dip was because of a fail mark amongst the cohort. If that fail mark is controlled for, then the average percentage had crept up from 2015/16. There was a clear increase in the percentage of distinctions, which had gone up to

25.8% from 20% in the previous year. The cross-over had been

from the students who had been in the merit range. Clearly, some students had been able to use the rubric to improve the standards of their essays. I found the provision of feedback much easier in 2016/17 because I had clear direction from the rubric. When giving feedback I explained both the strengths and weaknesses of the essay in relation to each criterion. My hope was that they would apply the advice more generally across other modules as the method of assessment is the same across board. In 2017/18, the average mark for the same module went up to 68.84%. 38% of the class attained distinctions; with 3% attaining more than 80%. Hence, in my third year, I have also been able to utilise step-marking in the distinction grade which has enabled me to meet the university’s policy.

When I introduced the rubric in 2016/17, I had a control module, by which I mean a module in which I neither provided the rubric nor spoke to the students about their assessments in detail. The quality of assessments from that module was much lower than the others where the students had been introduced to the rubric. In that year, the average grade for the control module was 60%; with 20% attaining a distinction and 20% failing. In 2017/18, while I did not provide the students with the rubric, I spoke to them about the assessments. The average grade for the control module was 61.2%; with 23% attaining a distinction. There was a reduction in the failure rate to 7.6%. The distinction grade also expanded, with 7.6% attaining a higher distinction grade. There was movement both from the failure grade and the pass grade to the next standard/performance level. Though I did not provide the students with the rubric, I still provided feedback to the students using the rubric as a guide. I have found that it has become ingrained in me and is a very useful tool for explaining the reasons for my grades to my students.

From my experience, I can assert, justifiably, that the rubric has played a very important role in improving the students’ essay outputs. It has also enabled me to improve my feedback skills immensely.

REFLECTIONS

I have observed that as the studies in the field argue, it is insufficient merely to have a rubric. For the rubric to achieve the desired objectives, it is important that students actively engage with it. I must admit, that I did not take a genuinely constructivist approach to the rubric. I wanted to explain myself to the students. I did not really encourage a 2-way conversation as the studies encourage and I think this affected the effectiveness of the rubric.

In 2017/18, I decided to talk the students through the rubric, explaining how they can use it to improve performance. I led them through the rubric in the final or penultimate class. During the session, I explained how they might align their essays with the various performance levels/standards. I gave them insights into some of the essays I had assessed in the previous two years; highlighting which practices were poor and which were best. By the end of the autumn term, the first module in which I had both the rubric and an explanation of its application in class saw a huge improvement in student output as set out in the section above. The results have been the best I have ever had. As the standards have improved, so have the grades. As stated above, I have been able to achieve step-marking in the distinction grade while improving standards generally.

I have also noticed that even where a rubric is not used but the teacher talks to the students about the assessments and their expectations of them, students perform better than where there is no conversation at all. In 2017/18, while I did not provide the rubric to the control-module, I discussed the assessment with the students, explaining practices which they might find helpful. As demonstrated above, there was lower failure rate and improvement generally across board. I can conclude therefore that assessment criteria ought to be explained much better to students if their performance is to improve. However, I think that having a rubric and student engagement with it is the best option.

I have also noticed that many students tend to perform well; in the merit bracket. These students would like to improve but are unable to decipher how to do so. These students, in particular, find the rubric very helpful.

In addition, Wolf and Stevens (2007) observe that rubrics are particularly helpful for international students whose assessment systems may have been different, though no less valid, from that of the system in which they have presently chosen to study. Such students struggle to understand what is expected of them and so, may fail to attain the best standards/performance levels that they could for lack of understanding of the assessment practices. A large proportion of my students are international, and I think that they have benefitted from having the rubric; particularly when they are invited to engage with it actively.

Finally, the rubric has improved my feedback skills tremendously. I am able to express my observations and grades in terms well understood both by myself and my students. The provision of feedback is no longer a chore or a bore. It has actually become quite enjoyable for me.

FOLLOW UP

On publishing the rubric to students:

I know that blackboard gives the opportunity to embed a rubric within each module. I have only so far uploaded copies of my rubric onto blackboard for the students on each of my modules. I have decided to explore the blackboard option to make the annual upload of the rubric more efficient. I will also see if the blackboard offers opportunities to improve on the rubric which will be a couple of years old by the end of this academic year.

On the Implementation of the rubric:

I have noted, however, that it takes about half an hour to explain the rubric to students for each module which eats into valuable teaching time. A more efficient method is required to provide good assessment insight to students. This Summer, I will liaise with my colleagues, as the examination officer, to discuss the provision of a best practice session for our students in relation to their assessments. At the session, students will also be introduced to the rubric. The rubric can then be paired with actual illustrations which the students can be encouraged to grade using its content. Such sessions will improve their ability to self-evaluate which is crucial both to their learning and the improvement of their outputs.

LINKS

• K. Wolf and E. Stevens (2007) 7(1) Journal of Effective Teaching, 3. https://www.uncw.edu/jet/articles/vol7_1/Wolf.pdf

• H Andrade, Y Du and K Mycek, ‘Rubric-Referenced Self- Assessment and Middle School Students’ Writing’ (2010) 17(2) Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy &Practice, 199 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/09695941003 696172?needAccess=true

• S Brookhart, How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading (Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development, ASCD, VA, 2013).

• Turnitin, ‘Rubrics and Grading Forms’ https://guides.turnitin.com/01_Manuals_and_Guides/Instru ctor_Guides/Turnitin_Classic_(Deprecated)/25_GradeMark

/Rubrics_and_Grading_Forms

• Blackboard, ‘Grade with Rubrics’ https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Grade/Rubrics

/Grade_with_Rubrics

• Blackboard, ‘Import and Export Rubrics’ https://help.blackboard.com/Learn/Instructor/Grade/Rubrics

/Import_and_Export_Rubrics

Student Minds is the UK’s Student Mental Health Charity, and was RUSU’s charity of the year for 2018/19. Student Mind’s aspiration is to ensure students have the skills, knowledge and confidence to talk about their own mental health and look out for their peers. To this end they provide research-driven training and supervision to university staff to enable students to be equipped to bring about positive change on their campuses through peer support.

Student Minds is the UK’s Student Mental Health Charity, and was RUSU’s charity of the year for 2018/19. Student Mind’s aspiration is to ensure students have the skills, knowledge and confidence to talk about their own mental health and look out for their peers. To this end they provide research-driven training and supervision to university staff to enable students to be equipped to bring about positive change on their campuses through peer support. The objectives are:

The objectives are: