Amanda Millmore, Sharon Sinclair-Graham, Dr. Rachel Horton, Darlene Sherwood, Sheldon Allen, Lauren Fuller, Konstanina Nouka, Will Page & Jessica Lane

School of Law (& Disability Advisory Service)

Overview

This student-staff partnership included students with disabilities and long-term conditions, academics in the School of Law and a Disability Advisor. Student partners ran a cohort-wide questionnaire and facilitated focus groups with disabled students to discover what has worked well this academic year with blended learning and where things could be improved. This work has provided a blueprint for those hoping to use blended learning to deliver accessible education for all.

Objectives

- To magnify the voice of our disabled students

- To understand the positives and negatives of blended learning from their various viewpoints

- To improve current teaching, as well as planning for future teaching and learning activities.

Context

The move to blended learning during the Covid-19 pandemic led to many changes to of the way that Law was taught in the 20/21 academic year. Student-Staff Partnership Group (SSP) feedback indicated that disabled students were affected more than most by this change. This project was an opportunity to understand more about the impact on these students and to amplify their voices.

Implementation

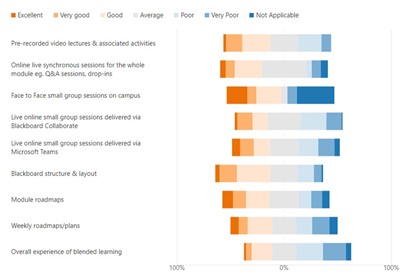

Given the constraints of working during the pandemic, our partnership worked virtually throughout, using only MS Teams meetings and sharing documents. Students designed a cohort-wide questionnaire to find out about the wider student experience with different aspects of blended learning.

This was followed-up by student partners facilitating smaller focus groups of students with disabilities and long-term conditions.

The partnership then assimilated all of the evidence they had gathered to produce short term and long term recommendations as well as highlighting what has worked well with blended learning.

Together we prepared a report with our evidence and recommendations and this has been shared not only within the School of Law but widely across the University, including with the University’s Blended Learning Project, the Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) team and the Committee on Student Experience and Development (COSED), as well as with colleagues in different functions and departments.

Impact

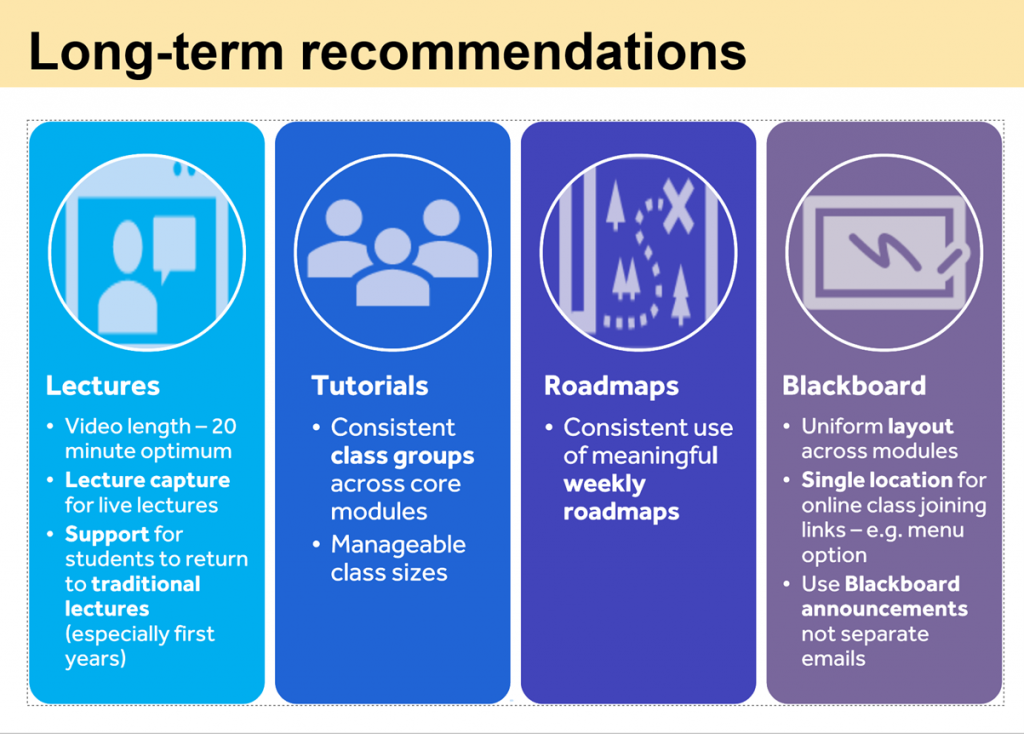

Positives from blended learning were highlighted including the flexibility of pre-recorded lecture videos, which enabled students to stop, pause and revisit lecture materials and work at their own pace and in their own time. Students preferred lecture recordings to be in the region of 20 minutes, as longer than that could pose a barrier for some students.

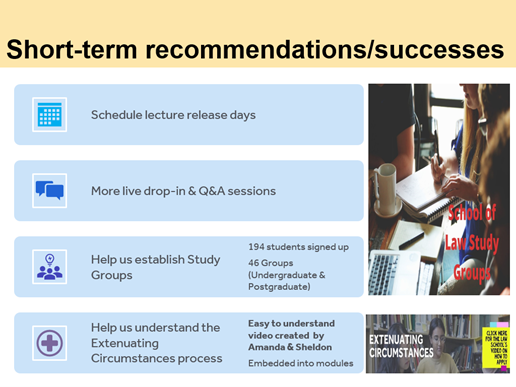

In the short term the partnership recommended the scheduling of lecture release days across core modules, so that lectures were made available on set days. 194 students were put into 46 study groups and a video to demystify the ECF process was recorded and shared widely (https://web.microsoftstream.com/video/714b6fa4-83f3-457c-a37b-3f4904e63691). These recommendations were all adopted.

Longer term the partnership recommended the consistent use of meaningful weekly plans (now part of the Teaching & Learning Framework for 2021/22) and improvements to Blackboard, notably a uniform layout across modules for Law students, including a single menu location for joining links to online classes.

The project and its recommendations have been shared within the School of Law, across the University and more widely at national conferences, all with students co-presenting the work.

Students were invited to the School of Law’s Blackboard Working Group and have been instrumental in driving forwards their recommendation for a consistent cross-module Blackboard layout for the next academic year. Students are also working with the TEL team to produce best practice videos for staff.

Reflections

This has been a hugely successful partnership project, not merely for the clear recommendations and tangible outcomes which are aimed to improve the experience of all students with blended learning this academic year and moving into the future, but also in the way that it has amplified the voices of students with disabilities and long-term conditions at School and University level.

As a partnership it has been influential, and the recommendations have been heard across the university and many have been adopted within the School of Law, but the positives for the individual student partners cannot be underestimated. They have gained valuable employability skills and experience in project work, presenting at conferences and advocating within meetings with staff. Moreover, as a project in which clear recommendations were given which have been heeded, it has improved the sense of community for all students, emphasising that the School of Law is a space where student views are important and they can contribute to their studies and make a difference.

Focus group participants with disabilities and long-term conditions have been empowered, with 2 first year participants subsequently volunteering for a new partnership project being run in the School of Law, as they can see the impact that their involvement can have.

Links and References

- Amanda Millmore – “A Student-Staff Partnership exploring the experience of disabled Law students with blended learning at University of Reading, UK “ in Healey, R. & Healey, M. (2021) Socially-just pedagogic practices in HE: Including equity, diversity, inclusion, anti-racism, decolonising, indigenisation, well-being, and disability.mickhealey.co.uk/resources

- Abstract for Advance HE Teaching & Learning Conference session: Teaching and learning conference – on demand abstracts_0.pdf (advance-he.ac.uk)

- To follow – links to CQSD TEL videos & guidance (in progress).

- We are happy to share the project report upon request – please get in touch if you would like a copy.