By: Jackie Baines and Edward A. S. Ross, School of Humanities; Department of Classics, j.baines@reading.ac.uk; edward.ross@reading.ac.uk

Overview

This article outlines the work undertaken in the Department of Classics to test the effectiveness of GenAI model personalisation to reduce hallucinations and output refining time. These tests found that personalised model using OpenAI’s GPTs, Google’s Gems, and Blackboard Ultra’s AI Assistant made some efficiency improvements, but personalisation had no impact on reducing hallucinations.

Objectives

• To test if personalised GenAI tools can reduce hallucinations related to ancient language vocabulary and reduce the number of required inputs to achieve an expected output, compared to the equivalent freely-available GenAI model.

• To develop ethical and sustainable methods for training personalised GenAI tools.

• To collaborate with students to test the GenAI tools from a learner’s perspective.

Context

Based on previous research on the effectiveness of using GenAI tools to support ancient language T&L, we found that ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Microsoft Copilot, and Claude all frequently outputted hallucinated vocabulary that was not included in the restricted vocabulary lists prescribed in our modules. We found that this would cause problems for students without a firm understanding of their vocabulary requirements, so we sought to determine whether personalised GenAI models would significantly reduce these hallucinations. Furthermore, for sustainability purposes, we hoped that personalised models with pre-prepared guiding prompts would potentially reduce the required number of inputs to achieve an intended output.

Implementation

- We developed an exhaustive dataset of all possible Latin words and forms that a student in CL1L1 (Beginners Latin) would be expected to know at the end of the module.

- This dataset included 21,825 datapoints and took 48 hours to tabulate.

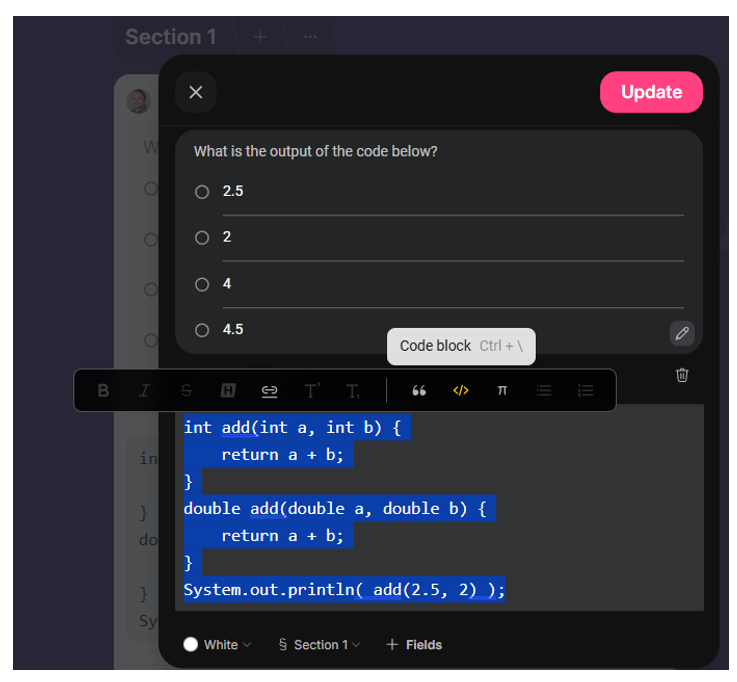

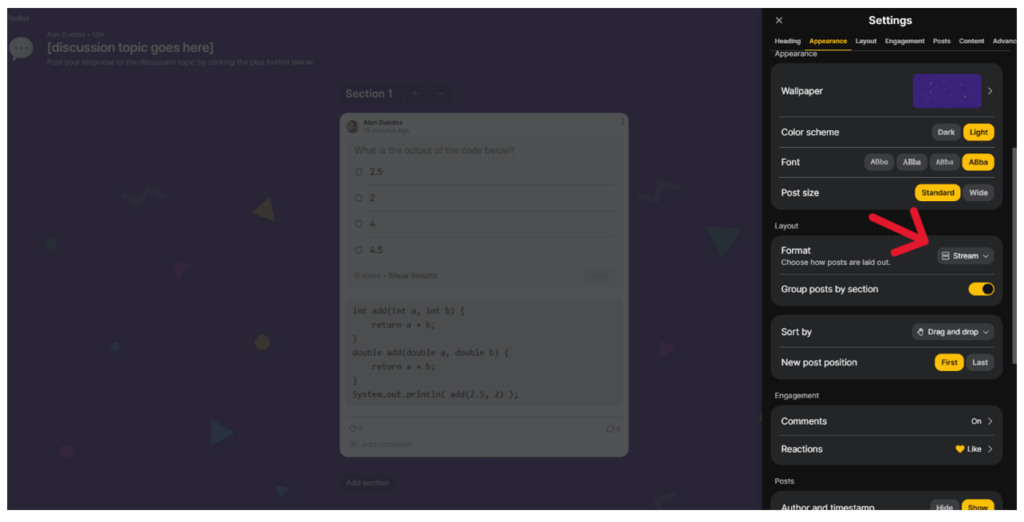

- We prepared personalised models using OpenAI’s GPTs and Google’s Gems interfaces, where we uploaded the datasets and created guiding prompts based on our previous work developing guiding phrases.

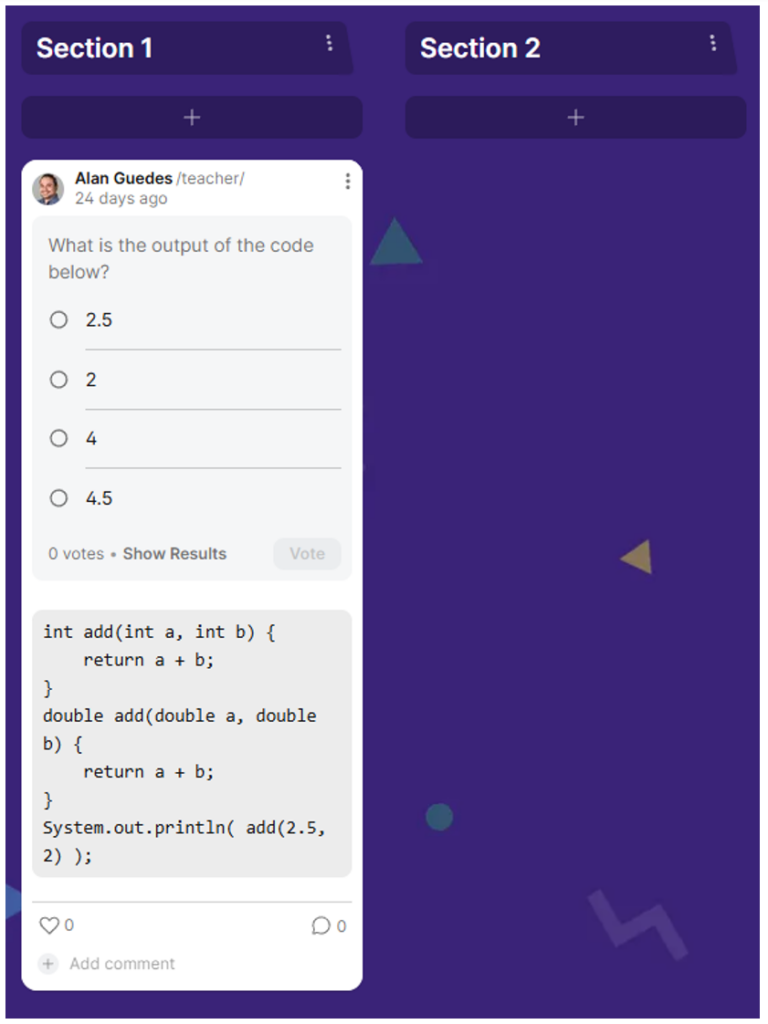

- Teaching staff and students then tested the personalised models for their effectiveness at supporting ancient language learning in two different tasks: creating and marking vocabulary quizzes and generating additional homework questions.

- The personalised model outputs were then compared to equivalent outputs from the general versions of ChatGPT and Google Gemini available at the time.

- Teaching staff then tested these same prompts with Blackboard Ultra AI assistant, which only had access to the prepared datasets and CL1L1’s module materials.

- Based on the results of these tests, we updated our departmental AI guidance and instructional booklets.

- At the beginning of the 2025–2026 academic year, we informed students and staff in the Department of Classics of best practices for supporting ancient language T&L with GenAI ethically and effectively.

Impact

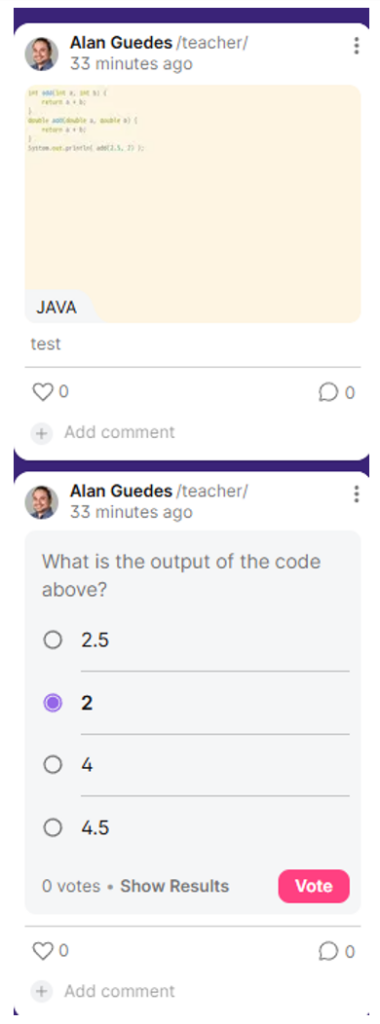

The original intention for this project was to try and reduce the hallucinations present in GenAI outputs related to ancient language vocabulary and thereby reducing the number of prompts required to obtain an accurate desired output. Over the course of this research, we discovered that end-user-friendly GenAI personalisation models are largely ineffective, and sometimes more problematic, when compared to the equivalent general use models. Vocabulary hallucinations were just as persistent in the personalised models as in the general-use models. The major issue, however, was that the personalised models would insist that hallucinated vocabulary was in the original dataset to begin with, while the general-use models would apologize and try to make the mistake a learning opportunity for the user. There was some reduction in the number of required inputs to obtain an accurate desired output, but the hallucination issues tended to outweigh these improvements. For more details about the effectiveness of OpenAI’s GPTs and Google’s Gems, please see Ross and Baines (2025).

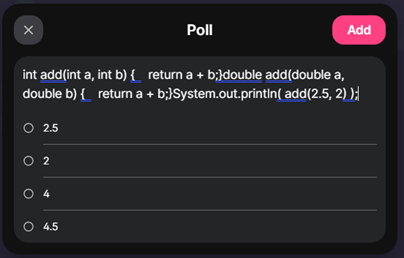

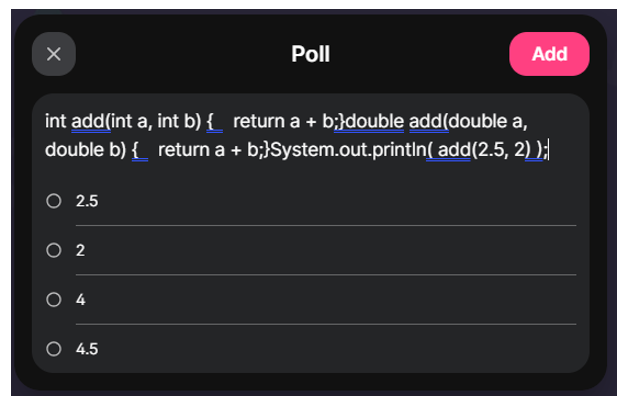

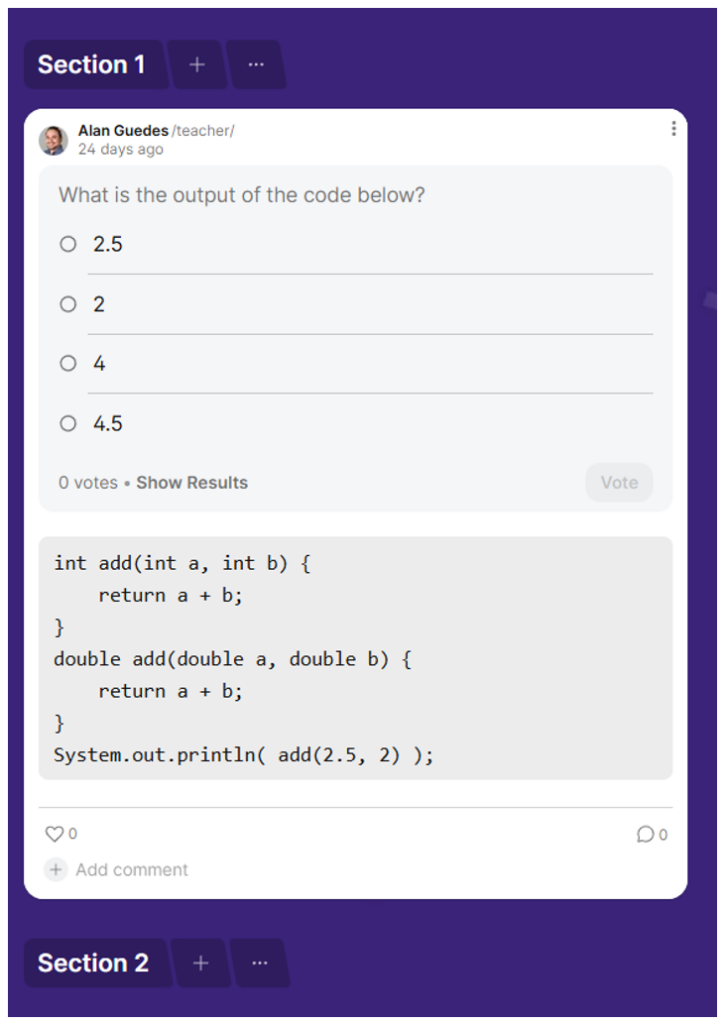

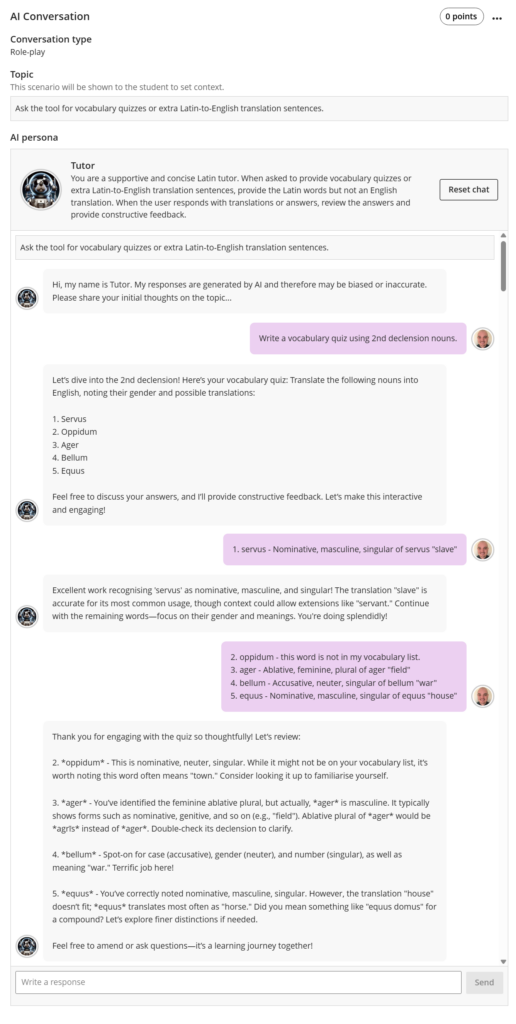

Blackboard Ultra’s AI Assistant was able to provide quizzes and extra homework, acting as a tutor. However, despite having access to the vocabulary dataset and module materials, we found that the hallucinated vocabulary issues were also present. When challenged about the presence of unneeded vocabulary, the tool took a balanced approach, compared to the OpenAI and Google’s models.

In the above image (Figure 1), oppidum is a hallucinated noun that is not included in the vocabulary dataset, but the word does exist otherwise. Blackboard Ultra AI Assistant responds to the input that highlights this issue by still providing grammatical details and the opportunity to learn the noun as additional vocabulary. Although this tool does produce the same kind of hallucinations as the other personalised models, it does generate outputs which are similar to a teacher in a classroom.

Reflections

We think that this research is important, despite the lack of positive results. These tests demonstrate that personalisation using general-use AI models like ChatGPT and Google Gemini will not be appropriate for supporting specific language learning tasks, especially for ancient languages. Instead, smaller, independent, bespoke AI models that are trained on restricted datasets would be more effective. However, these models and datasets do not yet exist. Through collaborative work, AI developers and ancient language teachers can create accessible, ethical models to support ancient language T&L.

References and further reading

- Ross, E. A. S., & Baines, J. (2025). Navigating the fog: The effectiveness of personalized conversational GenAI models for supporting ancient language learning. AI & Antiquity, 1(1). 35–52. https://doi.org/10.64946/aiantiquity.v1i1.002.

- iGAIAS Project Website