Michael Lyons- School of Literature and Languages

Overview

PEBLSS (a Partnership to Enhance Blended Learning – between Staff and Students) was a project seeking to strengthen teaching and learning in SLL. It particularly focuses on enhancing methods of teaching and learning amidst the extraordinary conditions faced by staff and students which has resulted in the transition into blended and online learning.

Context

A survey was designed and sent to students within the School of Literature and Languages, to identify members of staff who have excelled at blended learning during the Covid-19 pandemic 2020-2021. This was done by identifying three key areas of learning (pre-recorded lectures, live sessions, and assessment) and asking students to name the members of staff whom they believe stood out based on each of these core areas and their reasons behind this. Interviews were conducted to complete case studies based on these responses. Overall, 76 students responded to the survey.

We aimed to reduce “survey fatigue” due to the substantial number of surveys that students have received throughout the course of the Covid-19 pandemic. Therefore, by keeping the questions to short answers and multiple-choice, students were more likely to respond and contribute their ideas within the survey.

Once the surveys were collected, the results were analysed to identify the members of staff that proved to have stood out among the students in each of the core areas. From this, interviews were arranged and conducted to allow for the chosen members of staff to expand on their experience of teaching during the blended learning approach.

Objectives

The questions were designed to obtain specific examples of good teaching practices, and for the members of staff to

- elaborate on their successful methods.

- discover what teaching practices were successfully put into place and the ways they could be adapted into future teaching.

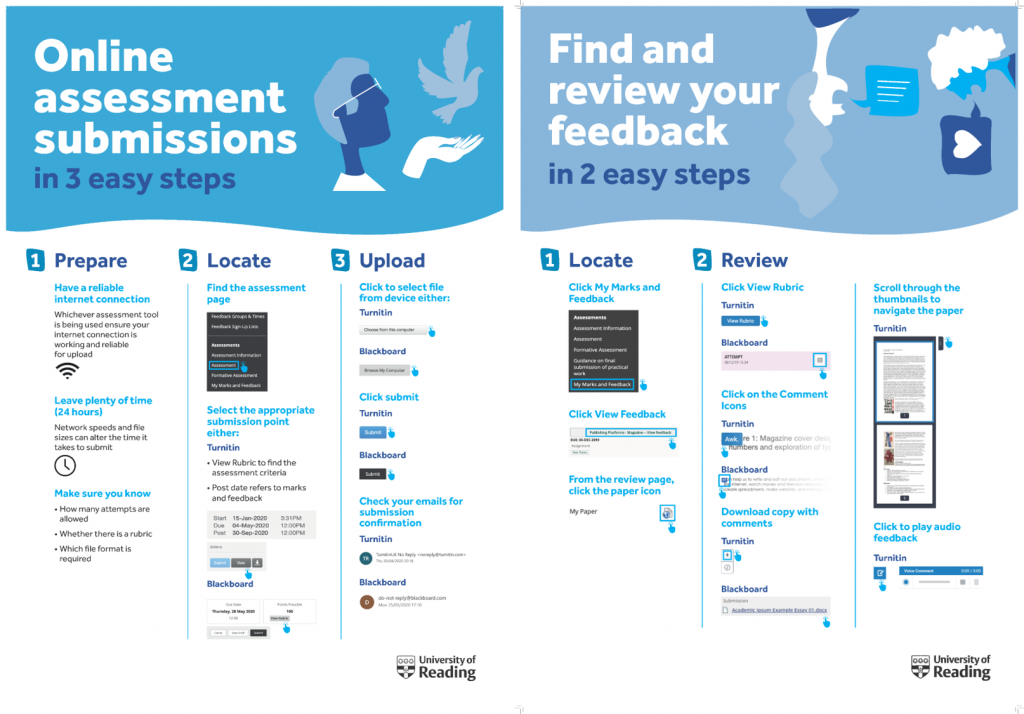

- retrieving information from nominated staff regarding how they continued to carry out assessments and ensure students felt supported in their assessments in the transition to the blended learning environment.

Implementation

Thirty minutes was designated per interview; however, many of the interviews extended beyond the time frame due the detail of the answers. Interviews were recorded and saved onto Microsoft Stream, for the researchers to conduct further analysis.

Impact

Summary of findings for the pre-recorded lectures

- Pre-recorded lectures offered the opportunity to bring in new, innovative audio-visual materials to support and enhance sessions. It was noted that different modes of delivery are important.

- Pre-recorded lectures were received well when language and style of speech was concise but exaggerated. More emphasis is needed on the speech style rather than gestures (and other paralinguistic features), as these are lost online. Additionally, potentially politically sensitive topics need extra consideration for online sessions.

- Guides about timeframes (like a week-by-week schedule) are useful for the organisation of pre-recorded lectures. Students know what they are learning when; examples of these practices were demonstrated in the interviews by a word document calendar, or a weekly bitesize email.

- It was advised that longer segments for the pre-recorded lectures should be avoided. 20-minute segments were recommended, as this makes the sessions concise but the content for the segment is still detailed,thus maintaining student engagement online.

- It is also advisable to have weekly folders, clearly labelled, with the pre-recorded lectures (with an embedded link), PowerPoint presentation, and any other specific resources or worksheets relevant to the screencast.

- It was noted that it was advantageous to have short videos of around 2-3 minutes in length to go over the concepts of the lecture; this makes it easier for students to revise. It also ensures that staff have covered important materials more than once e.g., prioritisation of information.

- Useful to have several check-ins with students near the beginning and middle of the module so that feedback about the pre-recorded lectures can be acted on whilst students are learning.

- Discussion boards were useful for the screencast exercises and promoted more student engagement. It was another useful tool for students to feedback about the screencasts, or if they had any questions.

- Timestamping information was beneficial. Outlining to students when certain parts or concepts are going to show in the pre-recorded lecture was advantageous because students can use the timestamps to revise specific information.

-

- It was noted that pre-recorded lectures were challenging because of the constraints of timing, editing and personalisation of content. Additionally, use of the pre-recorded lectures for the future was a topic under discussion in the interviews. Staff recognised the benefits of having the pre-existing screencasts; however, ensuring the information was up-to-date and engaging for current students was a concern. It was also noted that if the pre-recorded lectures were personalised this year for current students, the session would need to be updated or reproduced for the next year group.

Summary of findings for the live sessions

- The advantages of live sessions:

- Attendance is strong – reflected in the marking

- Online sessions easier than socially distanced face-to-face sessions for discussions and facilitating dialogue

- Sharing of files – OneNote/Blackboard/Collaborate

- The number of methods identified to help increase student participation

The disadvantages of live sessions:

- Technology – Learning new technology – reliance of technology, difficult if not working

Reflection

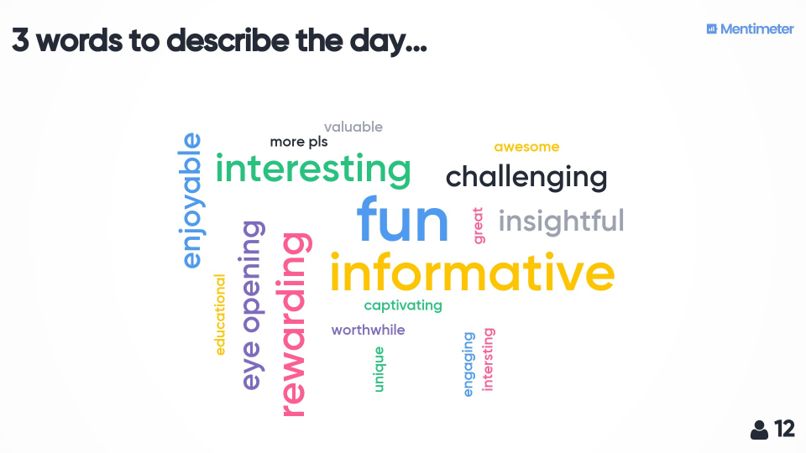

This project has been widely beneficial, not only in identifying current good teaching practices, but also finding methods to help for future pre-recorded lectures, live sessions, and assessments. The project was also beneficial for us as students. In identifying good practices during the pandemic, we were able to feed this information back to staff (and students) at the Teach Share event on the 29th of June 2021.

Overall, it is evident from this project that there are many teaching practices used by staff both before and during the Covid-19 pandemic that are beneficial to other members of staff (as well as the students) and therefore this project highlighted how important it is to share teaching practices, not only within individual departments, but school and university-wide.

Impact

Impact