Dr Alison MacLeod, Lecturer in Physical Geography and DSDTL, SAGES

This piece presents the view of students from one module in the University, it is not suggested that this view is shared by all students in the university.

Context

For context, this post relates to an Autumn term module, with 130 students which is assessed 100% by examination (part seen, part unseen). Delivery went well, student feedback was positive and we’d finished with an information session about the exam and the promise of an additional revision session early in the summer term to help them prepare.

Fast forward 3 months, we’re in lockdown, the University is preparing blanket extensions, safety nets, the circumstances impact process, take-home exams and much more. Students and colleagues are apprehensive about how it will all work. For me, this number of students taking an exam for 100% of their module in unfamiliar circumstances, and not having had any face-to-face contact since December was concerning. Students were prepared as well as possible, given the situation, with a full set of recorded lectures, journal articles, videos, podcasts, screencasts, Q & A forums, assessment literacy guide, sample answer structures and a promise that advice would be available during the exam to respond to queries about question wording, as an invigilator would.

The seen exam question was released on a Wednesday and unseen the following Tuesday. There were a few student queries here and there – referencing, citations, inclusion of figures, clarification of wording etc. but all students adhered to the rules and didn’t push for responses to questions I was unable to answer under exam conditions.

So exam done. How did it go? What was the student opinion? Did they hate it? Would there be a mass protest?

Findings

The following results emerged from 37 respondents to a BB survey (as of 15/05/20):

Clearly ensuring students are able to concentrate on their work in whatever setting they are in is important to producing their best work. The responses to this question generated perhaps a more variable response than some of the other questions, with some students finding it very difficult but others feeling more settled.

Figure 1- Ease of working at home

Further exploration of the reasons for this would be valuable to see if there was any way we could advise or support those students more effectively, and to examine if there is any correlation between their response and their exam performance. Some quotations from the students are as follows:

“I found revising at home very difficult.”

“It was better than I thought it was going to be….”

“Found it difficult to concentrate mentally because of personal circumstances etc, but the exam was clearly and practically explained so was easy to format correctly/submit and access.”

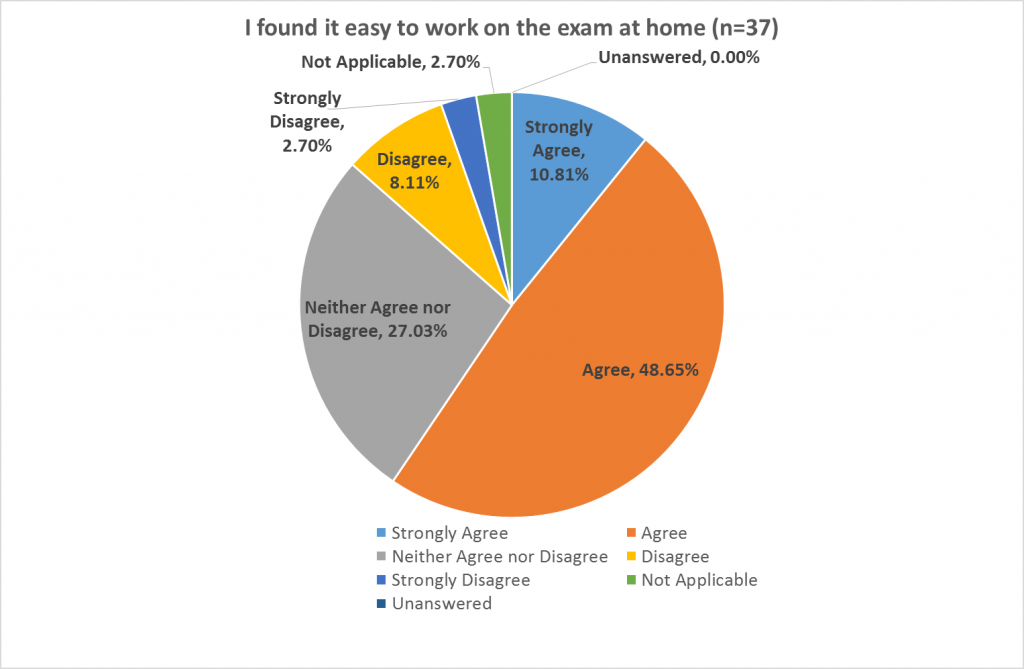

How long were students spending on their exams? Guidance was that they should spend about the same time as they would on a standard exam. For this module it was more complex as there was a seen and unseen component.

Figure 2- Time spent on both the seen and unseen component of the exam – the seen question was released 4 working days in advance of the exam and the intended formal duration of the exam was 2 hours

Analysing the data in Figure 2 as a whole, it is clear that a large majority of the students are spending significantly longer than recommended on the papers. From the free comments associated with the survey, this can possibly be put down to them appreciating the lower stress situation and having the time to be more thoughtful with their writing, however there was also a hint that this meant that there research/writing was less focused due to the extra time.

“Also, as most exams rely on memory, it felt rewarding that instead of simply regurgitating information, I was confident applying it and explaining it in more detail.”

“……. but I also found that because we had so long to answer the question, it made it quite difficult to write concisely and the extra time we had to check our answers, change things and add things etc. meant that my original ideas may have become convoluted.”

“I liked the fact that there wasn’t timed pressure, it felt more relaxed and I felt I wrote a better answer than I would have in a ‘normal’ exam.”

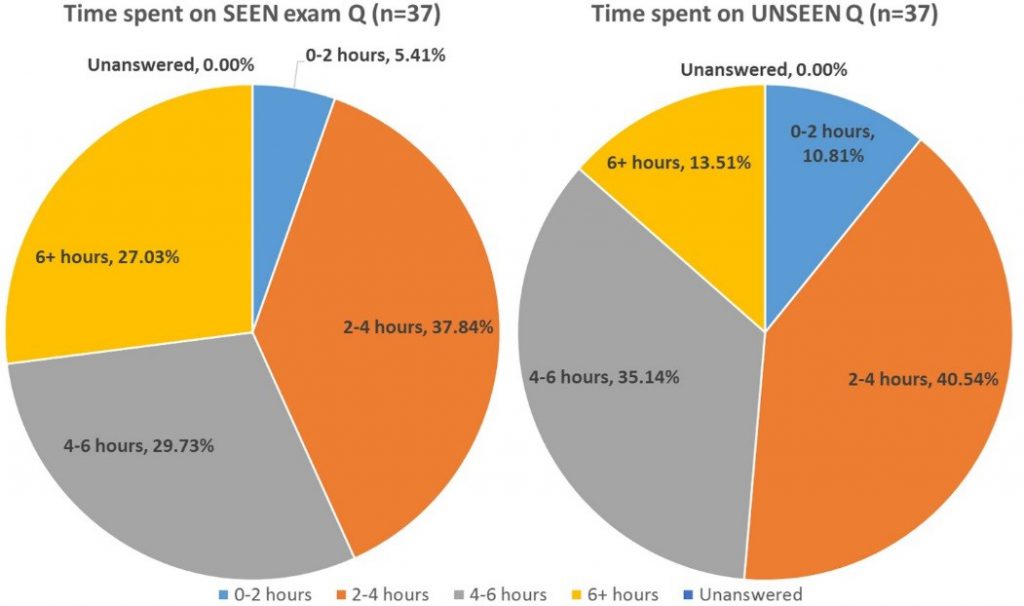

In this same vein, students appeared satisfied with the length of time they had available to them to complete the unseen component of this exam – with the caveat also that many modules may require students to complete two questions in this time rather than just one.

“a 23 hour time limit allowed me to properly formulate and deliver ideas I wouldn’t have had time to come up with in a regular exam.”

Figure 3- It was interesting to find out whether the students felt they had been given sufficient time to answer the question – this differs from Figure 1 in that it may be an indicator of how well they were able to balance this exam and other commitments

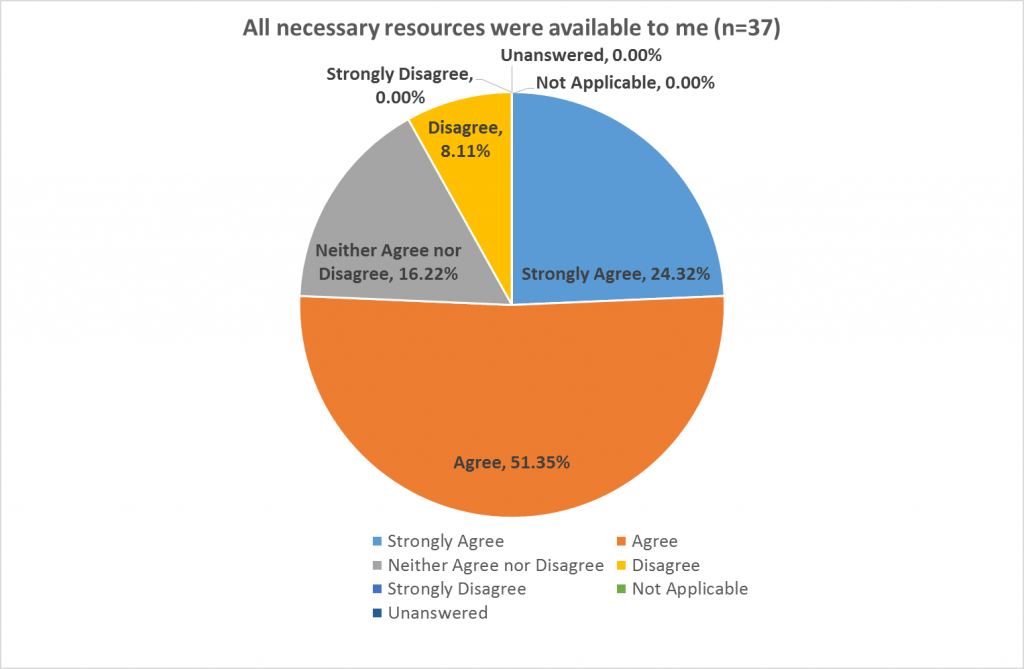

Something that could also have been problematic was the availability of resources – be that the general ability to access to the internet or more extensively to resources like, journal articles, books, perhaps even things like Q and A forums. Figure 4 demonstrates that in this instance, students were dominantly satisfied with the availability of the resources for this module, however there were a portion who found it more challenging.

“Revising was difficult without the access to the library”

“all the resources were easily available and the voice recordings of the lectures were really useful when revising”

Figure 4- Availability of resources to the students. It is noted that this includes a wide range of resources specific to this module but also incorporates access to things like e-books and journals.

In addition to this, students were also asked to comment on aspects like instructions provided for completion and submission of the exams. This was again very positive but with some clarity requested by some in relation to instructions:

“the instructions on how to submit the online exams were really clear and there was a lot of support provided to help with this”

“Submission via Turnitin was easy as usual, no problems. Maybe more clarity on what needs to be included on the document (e.g. candidate number over student number, module code)…”

Reflections

Overall this response was a pleasant surprise given the context that the students were working within, however there are some clear areas where it would be valuable to see if we can provide additional support or advice in advance of the Autumn term resits – studying at home being one. Only a small sample of the written quotes have been included here as an example.

Dr Alison MacLeod