Melanie Jay and Suzy Tutchell, Institute of Education

The Project

Seeds of Diversity was an ambitious, enriching and highly creative project drawing together the University of Reading’s community of teachers and learners to produce a collaborative and evolving sculptural installation. This innovative project celebrated the University’s roots and growth over the past 90 years as well as reflecting future aspirations. Sculptural ceramic seeds were created over 10 months and planted within the campus grounds’ as an installation and a final cross-disciplinary celebration at the end of the academic year.

Seeds of Diversity is now a sculptural installation made up of hundreds of ceramic seed pods created by partnership schools, staff, students, pupils and visitors. The creation of the pods was overseen by art-based tutors commensurate with existing and experimental customs and inspired by contemporary ceramic practice. Participants were invited to sculpt a seed in clay or to decorate a readymade form with a design which reflected their connection to the University.

Importantly, the workshop involved our ceramicist-in-resident, Sue Mundy. Sue, who is a prestigious artist in the world of ceramics and is an integral part of our ongoing vibrant artist-in-residency programme at the IoE, enriched the process further with her professional expertise and knowledge-base. The project naturally evolved over the duration of the year in response to a widening community interest stemming from our initial workshops. This development included working with Grant Pratt, a local raku expert, owner of Blue Matchbox Gallery in Tilehurst. Two raku firings provided participants with the opportunity to experiment with glazing and firing their pods in an outside kiln – this was a truly magical experience for all involved, even on the coldest of days.

“It was like a multi-sensory experience, the smell of the wood and burning materials was evocative of a smoke-house in Whitby!” (Andrew Happle, Lecturer in Science Education).

We worked with a varied and wide range of participants including:

- 5 x local primary schools

- Reading Boys school

- Wokingham secondary art teachers

- Primary Art Network teachers

- Secondary PGCE art students and D&T students

- PGCE primary students (whole cohort)

- BA Ed Y2 (whole cohort)

- BA Ed Art specialists (Years 1, 2 & 3)

- IoE Staff: Teaching and Research, Technical, Administrative

- Marvellous Mums project

- PGEYT students

Impact

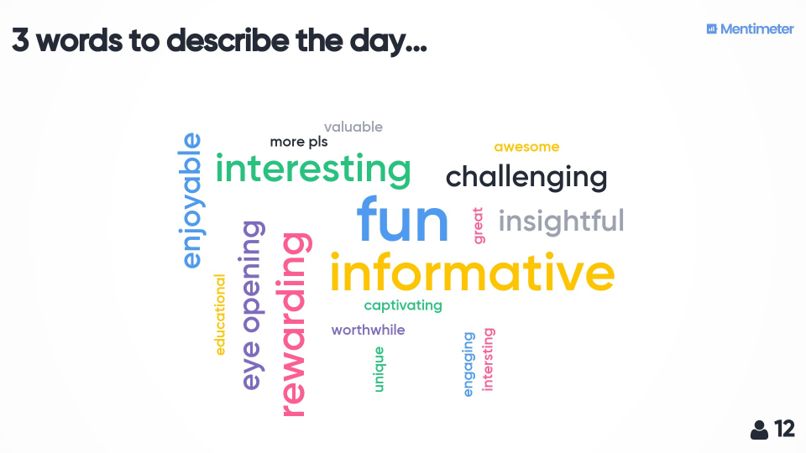

The impact of the project was multitudinous as highlighted by the following participants’ responses:

- To inform, extend and enrich staff and student learning, working in conjunction with existing teaching and resource-based facilities

“I feel the success of the project was heavily due to the incredible facilities that are available. Facilities that state schools cannot fund themselves and therefore providing the children with opportunities like this has been amazing.” (Katie Purdy, alumni and head teacher)

- To create a collaborative art installation on the University campus grounds:

“Every time I arrive in the mornings, no matter the weather, it’s such a treat to see the pods dotted around the campus and remember their creative beginnings” (Dr. Yota Dimitriadi, Lecturer in Computer Studies and National Teaching Fellow)

- To showcase the diversity and collaborative spirit of the University of Reading:

“The range of adults and children involved in the project was incredible, and was reflected in the final ‘look’ of the installation – a whole field of sizes, shapes, colours and individual characteristics” (Charlie Atkins, Y3 BA Ed Art specialist student)

- To symbolise UoR as a global and growing institution that works with individuals and communities to building knowledge and understanding for the future

“The Seed Project was a truly collaborative venture exemplifying the University of Reading as a sharing institution working with communities building and sharing knowledge for the benefit of all. This venture worked across departments in the making and the firing. During the raku even passers-by dropped in.

Each Raku firing is a fresh and exhilarating process every time I come to it and I am sure others felt the same. There are always new things to learn and new processes to try. Only one person can have the exciting task of loading the kiln and plucking the red hot pieces from the furnace but everyone is caught up in the thrill and joy of creating. The energetic beauty of the firing, the random, the accidental the unintended is captivating. Raku is all about community and as the clay transformed and the bisque reached a new stage the bond of the people in the group grew closer. It was an equalising activity as all ages and abilities learnt together. Earth, fire, and water were combined and it felt like Vulcan was awoken in everyone one of us” (Brian Murphy, former Assistant Head teacher and Head of the Faculty of Art and Design at The Piggott School, Wokingham)

- To provide a visual resource for staff, sightseers and repeat visitors

“I have been researching the University of Reading, London Road campus, but I went to the Raku firing out of an interest in the art rather than for my research. It did strike me that Art Education is still located in the same place that it was allocated when the University College moved onto the campus in 1905. And that the closest art building overlooks the lawns of the Palmer family home, where college staff played bowls during their leisure time” (Brian Richards, Emeritus Professor of Education)

Reflections

The project was highly successful as:

- We had a clear focus of what it wanted to achieve

- We had an academic year to carry out its work towards the final installation

- We represented a strong leadership of the arts, acknowledging specific contributions to the project from participants and collaborative partners

- The process of involving students encouraged a co-exploration between tutor and student in creative thinking and making. This was intrinsic to our teaching and learning sessions with a focus on skills and process development.

- IoE staff involvement in the making and enthusiastic ownership of the project and its final outcome raised the profile of art across the school and hidden individual creative skills were realised and ignited!

Challenge

- The only challenge (which could be seen as a successful outcome due to numbers) was making time for all participants to complete their work in time for the installation event.

Follow up

Owing to the collaborative and visual success of this project, we bid for and were successful in securing money from the university’s Diversity and Inclusion Funds and T&L Dean Funds in order to launch and roll out a new creative project for this academic year 2019-20 called Stitches in Time: Inclusive Threads of Learning. ‘Stitches in Time’ brings together Institute of Education students, staff and partnership schools to explore and discover sensory creative skills and contemporary imaginative thinking relating to textile materials and the environment. The project is taking place across a number of student-led workshops over the course of this academic year and will culminate in an evolving and diverse textile installation made up of participants’ individual work.