Julia Rodriguez Garcia: Department of Food and Nutritional Science

j.rodriguezgarcia@reading.ac.uk

Overview

This student-staff partnership involved students from all year groups, academics and the programme administrator of the BSc Food Science. In this PlanT project the Transforming the Experience of Students through Assessment (TESTA) methodology was used to develop programme focus assessment strategy that could lead to a reduction in volume and improved distribution of assessment, and overall enhance student and staff experience

Objectives

The main aim of this project was to take an evidence-based approach to enabling a cultural shift required from ‘my module’ to ‘our programme’ to engage staff in an integral restructuration of the assessment design, volume, and distribution in the programme.

The main objectives of the project were:

- To assess if there is assessment is evenly distributed in terms of volume and weighting and type across the programme

- To explore and propose changes in the design of assessment tasks to move to a programme level assessment strategy that could improve student and staff experience

Context

Restructuration of programmes have been usually performed at modular level, resulting in limited coordination of the learning (including assessment) strategy at programme level. In the BSc Food Science this led to student complains about high volume of assessment tasks due in a short period of time. External examiners also commented on the high volume of coursework components. And staff was overload with marking and feedback tourn around deadlines.

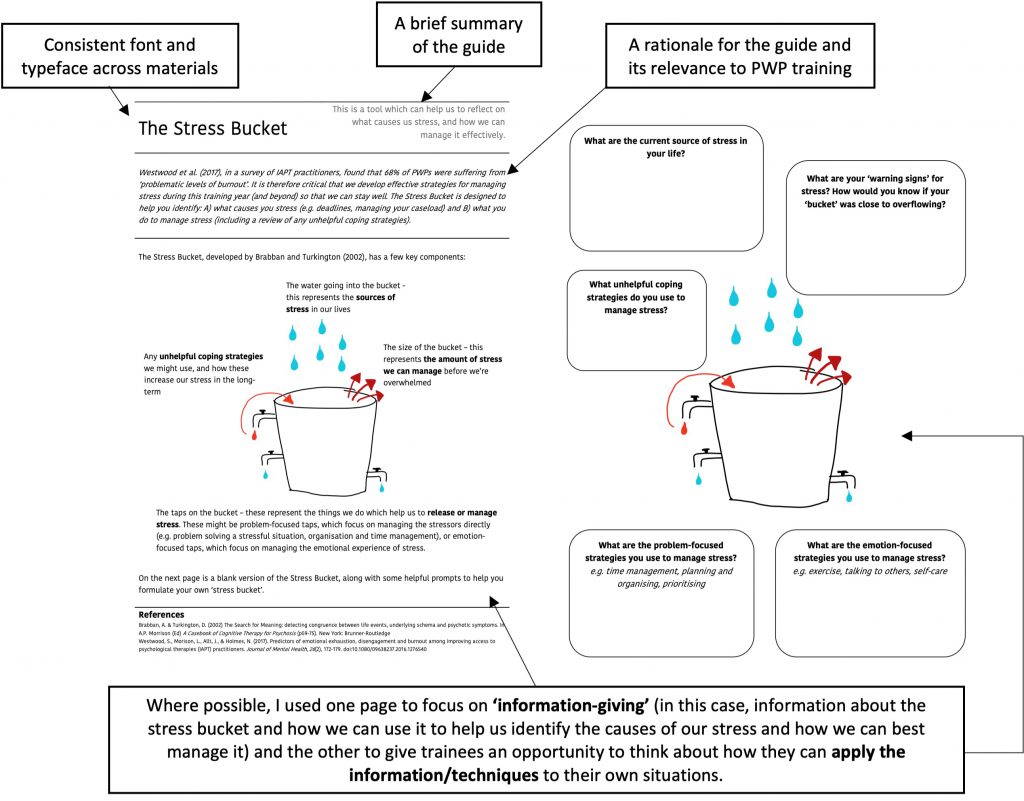

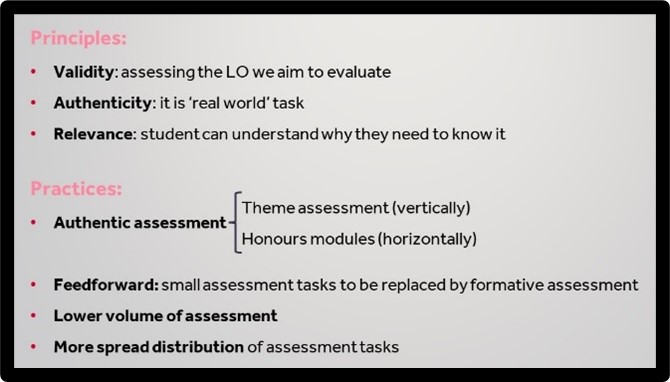

Having small assessment tasks set within a module, results in only a small number of concepts assessed as part of each task which leads to losing the holistic perspective of the subject area creating the effect of fragmenting knowledge and promoting surface learning, such as memorisation of content. Thus, a change from assessment of learning to assessment for/as learning will facilitate a change in behaviours improving students’ motivation and rewarding staff efforts

Implementation

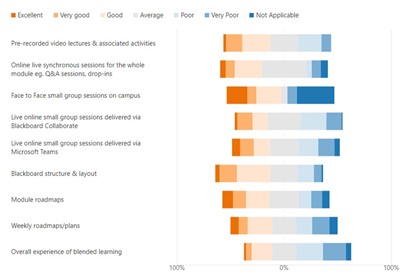

We developed Programme Level Assessment Maps that allowed us to calculate the number of assignments per credits, the weighting distribution per week and per term. These maps helped to create a visual interpretation of the students’ experience to increase staff awareness of the real situation at programme level (not just in their modules).

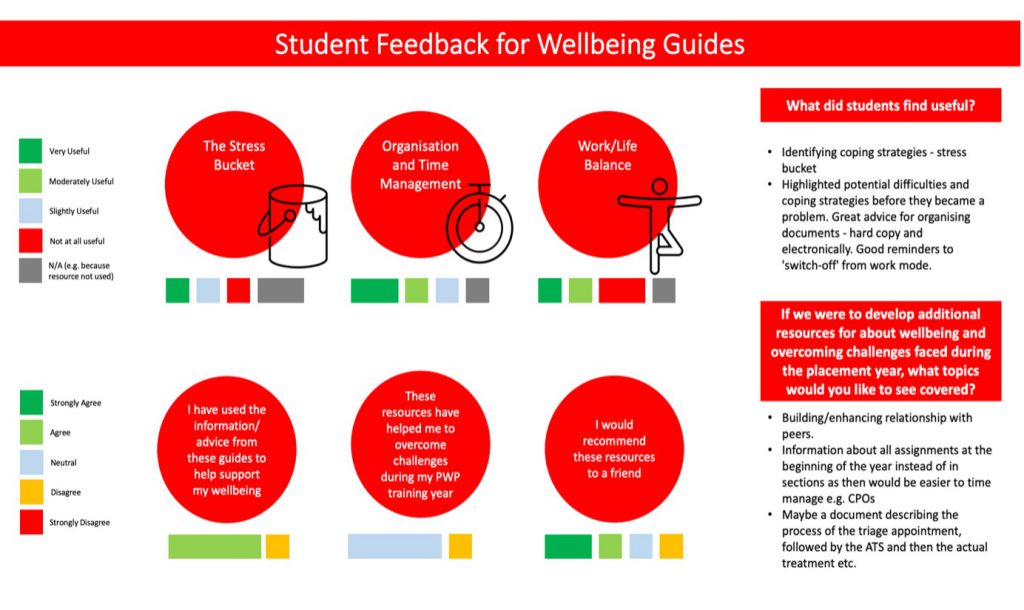

In collaboration with students, we modify the Assessment Experience Questionnaire to give students more space to reflect in their experience when performing certain type of assessments. This questionnaire was run two consecutive years.

One of the students leading the PlanT project carried out a focus groups with students from all year groups to reflect and discuss on the way they learn, the skills the develop and the challenges they faced completing assessment tasks.

We combined all the data, discussed it in light of published literature and draw some final suggestions to modify our assessment design practices. The results and future strategies were presented in a staff meeting lead by a student.

Impact

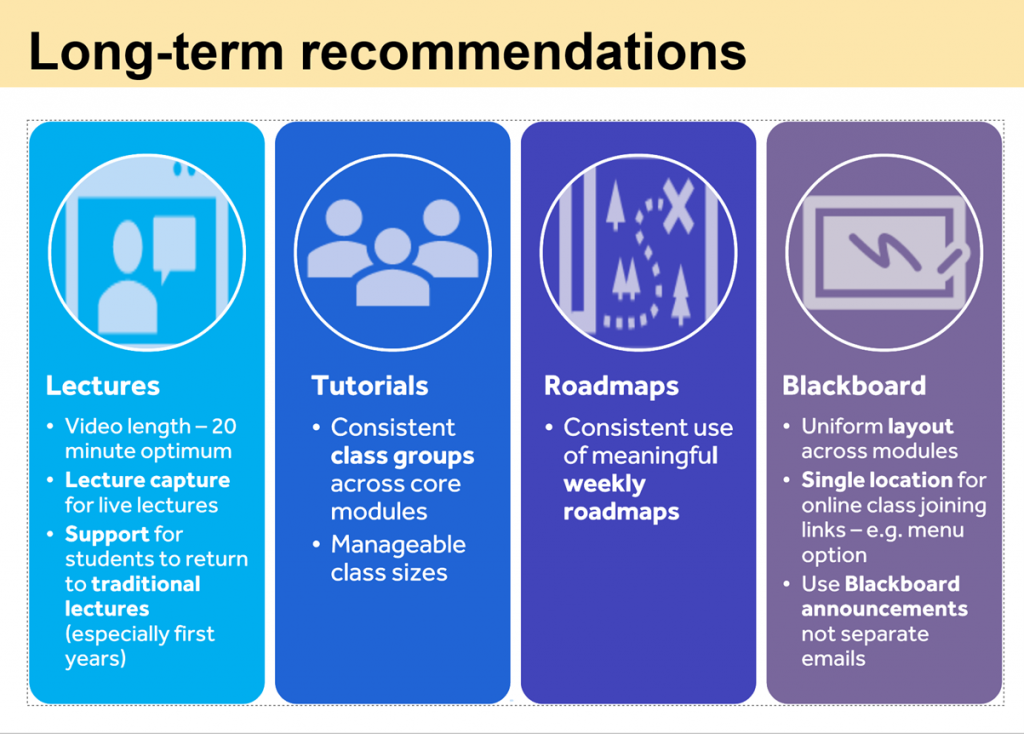

This project has facilitated and achieved a change in staff mindset from module level to programme level. This has been reflected in a 9% reduction on assessment activities from 2018-2019 to 2019-2020.

This shift in focus will allow us to perform more holistic changes following a common set of principles that underpin the development of authentic assessment to promote higher order thinking skills, integration of knowledge (horizontally and vertically), and students’ motivation and independence.

The conclusions from this project and the proposed strategies to develop a programme level assessment approach have been implemented in the department through the Portfolio Review

Reflection

The development of a cohesive staff community of Programme Directors, Module Convenors, and support staff from the teaching hub with strong communication links is crucial for the design and delivery of a high-quality programme.

Moreover, student voice and partnership are crucial for the co-development of teaching and assessment approaches, working collaborations are transformational both for the community wellbeing and for achieving highly successful outcomes. Development of a sense of community within the department is something distinctive in Food Science.

Follow up

Brown, Sally, and Kay Sambell. 2020a. “Changing assessment for good: a major opportunity for educational developers.” Assessment, Learning and Teaching in Higher Education; Sally Brown. https://sally-brown.net/kay-sambell-and-sally-brown-covid-19-assessment-collection/.

Murphy, Vanessa, James Fox, Sinéad Freeman, and Nicola Hughes. 2017. ““Keeping It Real”: A Review of the Benefits, Challenges and Steps Towards Implementing Authentic Assessment.”. The All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education (AISHE-J) 9 (3):2801.

O’Neil, Geraldine Mary. 2019. “Why don’t we want to reduce assessment?” All Ireland Journal of Higher Education 11 (2):1-7.

TESTA. Transforming the Experience of Students Through Assessment. https://www.testa.ac.uk/

Villarroel, V.; Bloxham, S.; Bruna, D.; Bruna, C.; Herrera-Seda, C. Authentic assessment: creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 2018, 43, 840-854, doi:10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396.