Vicky Collins

International Study and Language Institute, ISLI

Overview

Each year tutors on the Academic English Programme [AEP] run by ISLI participate in an internal show case of tips and best practices as a Peer Review event. This year we chose the theme of ‘Managing synchronous online teaching’ given the level of challenge it presents and creative solutions emerging to these. The event included a pre task, live demos and talks throughs, an external list of resources for participants, and a final compendium of curated videos (recorded from the live delivery) for wider dissemination in ISLI.

Objectives

The main aims of the annual Peer review event are:

- To draw out good practice and reflect on experiences of teaching on the Academic English Programme [AEP] from the previous year or term

- To foster a team environment by providing for a network to exchange ideas and experiences

Whilst acknowledging that there are many tutorials and training videos available widely to support online teaching, for this peer review on ‘Managing synchronous online teaching’ we were keen to draw out tips and practices developed in situ.

Context

Since September 2020, the whole AEP team has been involved in regular live online teaching. This includes all aspects of the Academic English Programme from discipline specific courses to webinars on particular aspects of academic language and literacy. Prior to this most of our experience and training for the transition to online T & L was around asynchronous delivery, so we thought a review and reflection of online synchronous teaching was timely

Implementation

I started by researching sub themes within ‘managing online synchronous teaching’ and developed a list from which to solicit ideas for tips and practices from the teaching team:

- Opening and closing a session

- Spaces for collaboration

- Tools for live interactivity

- Multitasking during sessions

- Working with longer texts online

- Teaching to the void: finding ways of connecting to students

- Staging & organising of activities

Soliciting, categorising and developing initial ideas in advance with colleagues helped avoid duplication and also meant I could allocate suitable timings to presentations/demos . The event was scheduled for 3 hours with rest breaks and question times and held on Teams. Given the commitment of time required, this peer review event takes place in January each year- before the Spring term gets underway and also to boost morale on return from the festive break.

Prior to the event I set a pre task on the topic of ‘What does live online learning look like for our discipline?’ . A discussion thread was set up and colleagues contributed voluntarily .

I also developed a list of external resources on the topic of online synchronous learning to share with participants after the event.

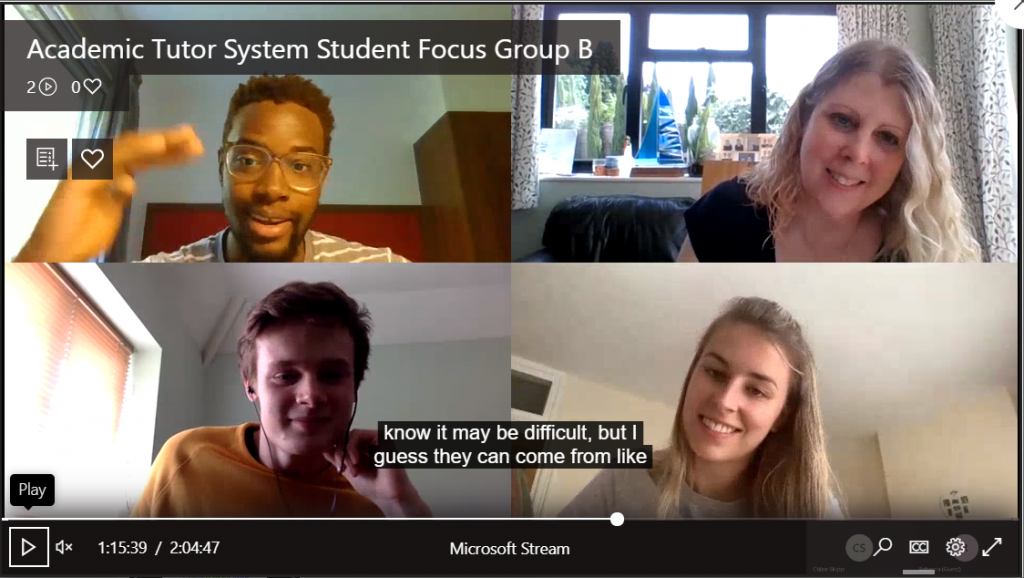

The Peer review event itself was recorded, with permission, and I then curated the individual presentations into 18 bite sized videos.

Impact

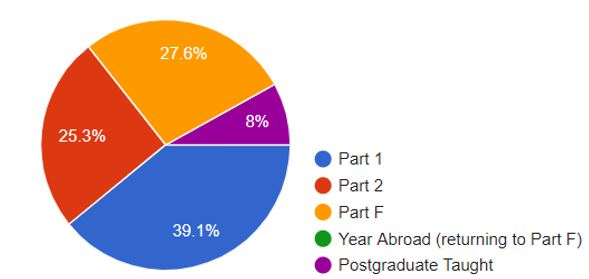

A feedback survey was issued once all resources had been released. This was completed by 8 out of 12 participants.

The aim of the feedback survey was to gauge satisfaction with the event and impact it had on participants preparedness for live online teaching this term [Spring 2021]

In terms of satisfaction, all participants strongly agreed that the event was effectively organized.

All participants strongly agreed [5] or agreed [3] that the event and resources helped them to feel more prepared. Varying levels of confidence in live online scenarios are reflected in participants’ familiarity with ideas presented by their peers. Most reported that between 25-50% of the activities were new to them, and two reported a greater percentage.

Participants listed a range of the tips and practices presented by peers that they would like to try out this term [Spring 2021]

Reflections

One of the most significant outcomes of this was that despite the plethora of tutorials and training vignettes on you tube for example, which teaching staff can consult, a genuine account of these tips and practices in situ is still much valued. My colleagues were able to discuss with sincerity the pros and cons of practices they had tried in the past term, and how they hoped to continue building on these. Comments to the pre task discussion question were insightful and I feel I learnt much from these as I compiled them into a summary. I felt this approach to peer learning was particularly conducive i.e giving peers a space to contribute to a thread, time to read through other contributions, and then for the facilitator to summarise this so we have a meaningful record of our thoughts and ideas. Not everybody in the team had the confidence to present or demo tips and practices, and indeed there was no pressure to do so, but the pre task allowed for them to contribute to the event in a another form

Follow up

- The feedback form included an area for participants to share what ideas from the event they would like to put into practice this term. I will informally review this at the end of the term[Spring 2021] and have set up a discussion thread for peers to comment on these

- Participants have given permission for their videos to be used more widely in ISLI for teacher development purposes.