By: Mirjana Sokolovic-Perovic & Joe Spackman, Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, m.sokolovic@reading.ac.uk, j.spackman@reading.ac.uk

Overview

This is an overview of a buddy system for speech and language therapy students which aims to support students’ academic and social transition to university and to enhance their sense of belonging and wellbeing. We paired each first-year student with a second-year ‘buddy’ and provided opportunities for the two cohorts to get together.

Objectives

- To support academic and social transition of first year MSc and MSci speech and language therapy (SLT) students

- To help build a community of students and a peer-support network

- To support development of students’ sense of belonging, and to enhance their wellbeing

- To enable students to start building a professional network

Context

Transition to higher education has been recognised as a multi-layered process involving academic, social and lifestyle adjustments. It has a long-term impact on students’ academic achievement and satisfaction, social integration, mental health and wellbeing, and retention rates (Briggs et al., 2012).

Peer support has been suggested as an effective strategy in supporting various aspect of student transition (Heirdsfield et al., 2005). For students on allied health programmes, Health Education England (HEE) have advocated for a student buddy scheme in HE institutions, advising it provides educational, social and pastoral support (Stokes, 2022). Peer-to-peer support adds an extra layer of student support and is often the first step in accessing professional services. HEE report on attrition and retention (Lovegrove, 2018) found that healthcare students who had participated in a buddy scheme felt it was important to settling into the course and helped with engagement, learning and any possible anxieties and fears.

This has led us to consider how the existing SLT peer-support scheme could be improved to aids SLT students’ academic and social transition.

Implementation

Recent feedback indicated that first year students felt anxious and sometimes lonely, not knowing what to expect from the programme and from day-to-day life as SLT students. They needed a wider community of SLT students they could reach out to for advice and support.

A buddy system has existed in Clinical Language Sciences department in the past, where each first-year student was paired with a second-year student (there are currently around 215 students on the two SLT programmes: approximately 40–45 students in each MSci cohort, and 20–30 students in each MSc cohort). However, it was left to students to initiate and maintain contact, and consequently the uptake was low and there was little impact on student experience. Unfortunately, during the Covid-19 pandemic and in the following years, this has fallen away, and the scheme was abandoned.

In academic year 2023–24, we decided to reconsider our approach and to revive the SLT buddy scheme, by not only pairing students from different cohorts, but also by providing them a safe space on campus where they could meet and socialise with students from the year above.

Students were allocated a buddy at random. Pairings were shared with both cohorts via email and advertised in teaching sessions. Students were invited to an informal get together where buddies could both meet each other in person and get to know the other cohort. Students were encouraged to either contact their buddy beforehand or to arrange to meet at the get together. Two different formats were used for MSci and MSc students because of different cohort sizes.

For the MSc SLT cohorts, which are smaller than the MSci groups, a room was booked on campus at a lunch time and both cohorts were invited. Attendance was high for this meeting. We organised a small ice-breaker activity and had talking point questions and well-being activities (colouring-in, pom-pom making) available. The students were very welcoming of each other and conversations started immediately and spontaneously throughout the session.

The MSci SLT cohorts are larger, and for this buddy get-together we booked two rooms, with the same format. However, the attendance was lower, so in the end we only used the larger room.

Impact

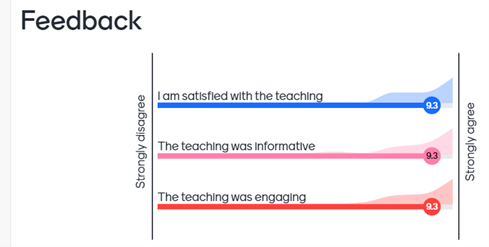

Participants were asked to complete a MS Forms questionnaire about their experiences. Student feedback was very positive overall, demonstrating achievement of our initial objectives:

‘It was so reassuring talking to the 2nd year students and widening our network of SLTs in the department. I intend to keep in touch with my buddy.’

‘Really good opportunities to mingle and talk. Like that it was a big group so we could meet more people than just our buddy….’

‘I thought it was a lovely idea. I got to speak to my buddy in a chilled environment.’

‘The informality of the session worked really well to get to know each other and find out about the specific information….’

Reflections

Buddy meet-up sessions were very successful. The atmosphere was relaxed and student feedback suggested that it helped them settle better into the new environment.

First year MSc students reported that speaking with a second-year buddy alleviated some of their anxieties about the workload and studying on a professional course. They suggested that they would prefer the buddy system to start earlier in the academic year, and to have regular meetups, which is something we will try to implement for the next year.

Our reflections on the lower attendance for the MSci cohort led us to consider whether there was some uncertainty among the second-year undergraduate students about the role of a buddy and expectations in terms of their engagement. We could have provided more support on this. HEE suggests creating a buddy fact sheet/contract to explain the scheme and boundaries (Lovegrove, 2018). Next year we plan to introduce this at the beginning of the process.

Following some feedback about the impact of interacting in a large space with multiple students, we will investigate different options for the environment to support students who may find this uncomfortable or challenging.

Follow up

Using an adapted Learning Cycle (Kolb, 1984), we will continue to refine the format of the buddy scheme, based on feedback from this year’s cohorts and subsequent cohorts, making sure that these events benefit all groups of students.

The reflections and recommendations on the SLT buddy scheme have been shared at an Advance HE Conference (May 2024) and PCLS Teaching and Learning Away Day (July 2024).

Links and further reading

- Spackman, J. (2024, May 15). Embedding mental health and wellbeing support strategies into MSci and MSc speech and language therapy curricula [research poster abstract]. Advance HE Mental Wellbeing in HE Conference 2024. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2024-04/Poster%20Abstracts%20-%20Mental%20Wellbeing%20in%20HE%20Conference%202024_3.pdf

References

- Briggs, A. R. J., Clark, J., & Hall, I. (2012). Building bridges: Understanding student transition to university. Quality in higher education, 18(1), 3–21.

- Heirdsfield, A., Walker, S., & Walsh, K. (2005). Developing peer mentoring support for TAFE students entering 1st-year university early childhood studies. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 26(4), 423–436.

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice Hall.

- Lovegrove, M. J. (2018). RePAIR reducing pre-registration attrition and improving retention report. HEE. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/RePAIR%20Report%202018_FINAL_0.pdf

- Stokes, J. (2022). Allied health professional student buddy scheme evidence-based guide. HEE. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/AHP%20student%20buddy%20scheme_4.pdf