By: George Pontikas & Emma Pagnamenta, Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, g.pontikas@reading.ac.uk e.pagnamenta@reading.ac.uk

Overview

This post outlines curriculum development undertaken as part of the MSci/MSc Speech and Language Therapy programmes to strengthen our students’ knowledge and understanding around research ethics, research governance, clinical audit, service evaluation and quality improvement and how these can be utilised alongside clinical practice. Activities were supported by external collaborators with leadership roles in the National Health Service (NHS) providing real-world experience of these processes.

Objectives

- To support Speech and Language Therapy students to develop professional competences in research focusing on ethics & governance and adherence to relevant processes and policies.

- To engage students in authentic activities assessing examples of audits, service evaluations and quality improvement projects which are common research-based activities in NHS services.

Context

Both the Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists and the Health & Care Professions Council stipulate a requirement for evidence-based practice and engagement in (ethical) research or research-related activities such as service evaluation. This aims to continuously improve and offer the best service to users and stakeholders. However, developing research skills can be challenging on programmes that require many hours of teaching across disciplines while completing placements.

Implementation

We designed a series of materials and activities around obtaining information and/or assessing a particular provision in an NHS service (audit, service evaluation, quality improvement). We selected a series of real examples from NHS services involving audits, service evaluation and quality improvement projects. Subsequently, we created a number of activities where students were asked to consider:

- the motivation for these projects,

- their relevance and appropriateness given the challenges faced in the services,

- their implementation and effectiveness and

- avenues for further action aiming to deliver optimal service.

The activities involved group discussion around a series of structured questions with students’ contributions collated on PowerPoint slides. For students to engage with these activities, we ran four 2-hour workshops in Semester 1 (for Part 3 MSci or Part 1 MSc students).

Involvement of (external) experts: This project was supported by three NHS practitioners with leadership roles (Dr Sam Burr, Dr Colin Barnes & Ophelia Watson, Solent NHS Trust) who:

- provided us with the relevant case studies from their own Trusts

- recorded screencasts on how their Trusts engage with either evaluating their service or involving the patients and the public in research, or

- attended workshops and co-taught with a UoR lecturer (Emma Pagnamenta).

Impact

This project has been running for three years. Overall, it covered a gap in the teaching on the speech and language therapy programmes on evaluation and research, aligned with professional standards, while enriching the student experience in terms of diversity of opportunities and learning activities.

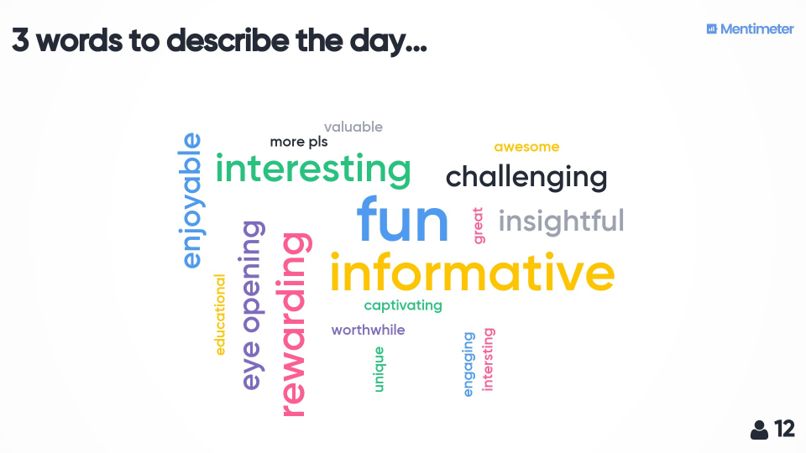

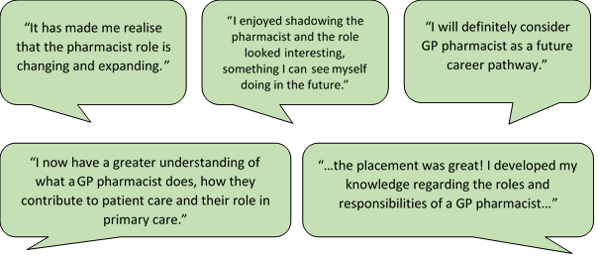

In the second year (2023–4) we obtained feedback from students specifically for this teaching this year. Responses were positive with over 80% students reporting that they were more interested in carrying out clinical research and/or service evaluation in their careers.

In 2023–4 and 2024–5, current students have been invited to showcase research projects from the Undergraduate Research Opportunities Programme (UROP) that have involved collaborative quality improvement initiatives between NHS services and UoR.

Reflections

We evaluated these activities this year informally. Students were generally positive about these activities with > 80% reporting that they have become more interested in clinical research/audit/evaluation. One student characteristically said that “[it] made research a lot more realistic to me”.

One challenge we faced was around the logistics of timetabling these sessions around external collaborators’ availability and fitting these sessions into an already loaded timetable. One way around this is to be flexible in terms of the contribution of our external experts – through using screencasts, joining teaching sessions remotely to present and answer questions, providing resources and examples. We hope this will enable a more long-term collaboration with external experts who have unique professional insights and experience given their roles.

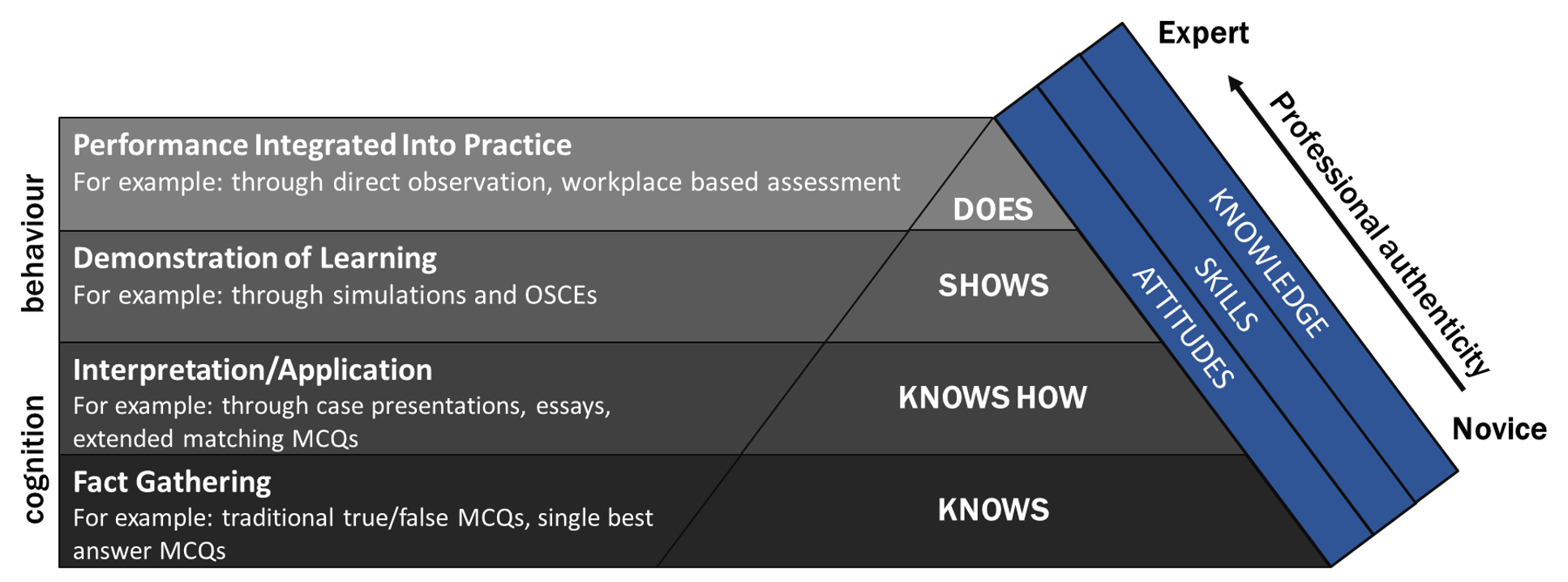

We believe having activities which are digitally enabled in this way can facilitate learning integrated in professional settings in other contexts across programmes.