By: Amanda Millmore, The School of Law, a.millmore@reading.ac.uk

Overview

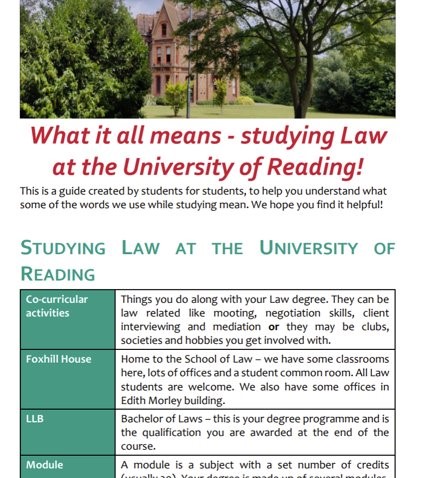

As a way of helping new students to transition to university, our student-staff partnership co-created a “Hidden Curriculum Glossary.” The original glossary has been shared with students in the School of Law, used as the basis for a guide for first generation students at the University of Reading and has been adopted and adapted by universities across the sector, both in Law and other disciplines.

Objectives

The “hidden curriculum” has varied definitions but relates to the lack of connection between academics’ assumptions about students and how they should behave and what happens in reality. This includes implicit aspects of the taught curriculum as well as the academic expectations. The project aimed to get first generation Law students to help new entrants to understand some of the terminology and behavioural expectations of university by co-creating supportive resources.

Context

The adverse impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on students’ sense of belonging has been challenging. This partnership project worked with first generation Law students to brainstorm ideas to improve a sense of community and belonging within the Law School. The project led to positive ideas to benefit our community, as well as the creation of resources to support transition for all students.

Implementation

We recruited 8 paid student-partners; we pay them for their time to ensure a diverse group of students and as always, we are adopting the University’s Principles of Partnership.

Together we shared ideas to improve the sense of community and belonging which were taken forwards by the School’s Student Experience Committee and we identified suggestions to help incoming students.

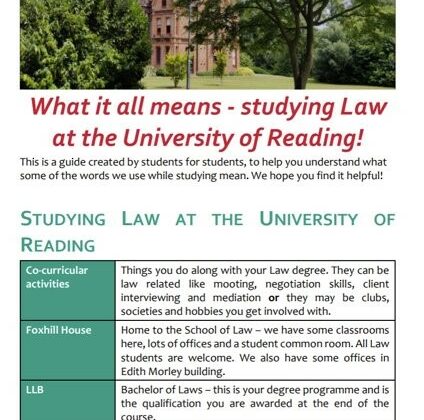

One important output of our partnership was our quick guide to terminology and expectations – the Hidden Curriculum Glossary. Students shared what they wished they had known before starting and in their first year of university, and we co-created a helpful and colourful document demystifying key terms and concepts, written in plain English and tailored for what new students need to know.

The glossary was printed and shared with incoming undergraduate and postgraduate students as part of their transition materials in Welcome Week. Students also created “Top Tips” videos for new students and a video guide to our building. All of the resources are also shared electronically via Blackboard.

We have updated the glossary each year to incorporate student feedback and to include any changes. So for example, in its second year we added in more information about the Careers team and how they can help students.

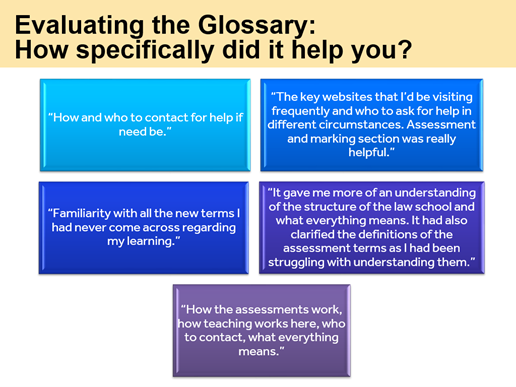

The glossary is designed to support student transition and retention. It received very positive feedback from Law students via a questionnaire to all who received it, for example here is some of the qualitative feedback we received:

Impact

Student partners disseminated the work at a Teaching & Learning Showcase and the Change Agents’ Network Conference 2023.

We created a Criminology version of the glossary for the new programme which was launched in 2023/24 and are now getting ready for the 3rd iteration of the glossary to incorporate the new language of semesters for 24/25.

The glossary is also a useful introduction to new colleagues joining the university, to get to grips with the language and terminology we use in Reading.

Reflections

Sometimes the simplest ideas are the best. The glossary has been a really useful exercise in co-creation with students, ensuring that we meet their needs and by making something of real value to them.

I would recommend that anyone looking to devise this kind of resource, looks to do so with student partners. Partnership working in this way ensures that the materials you produce are appropriate. As always with this kind of work, the students are fantastic at getting their teeth stuck into a project and make a real difference. Co-creation leads to sharing of different perspectives and is always eye-opening, unsurprisingly students know best as to what will resonate with their peers.

One of the biggest challenges was the timing of the project. Our funding did not kick in until August, but we needed to start work before then in order to achieve something useful in time for the start of the next academic year. Juggling student availability, when they have so many calls upon their time is always tricky, but keeping a flexible approach and realising that things do not need to be perfect, is crucial to a successful project.

Full credit to my colleague Dr. Başak Bak who worked on the community-building side of the project, and our fantastic student partners: Laura Carroll, Ambreen Azeem, Ryan Gibbard, Aina Binti Mohammad Abu Sofian, Srijanani Viswanathan, Saydee Brown, Lewis James, Hasti Houshyari and Kartiga Moganan.

Follow up

Having presented this work and its evolutions within Legal Education streams at Law-specific conferences (Society of Legal Scholars, 2023, Socio-Legal Studies Association, 2024) and at the Advance HE Teaching & Learning Conference (2023 & 2024), our glossary has been adopted and adapted by 8 other institutions (to date), many working to co-produce resources with their students:

2023

- University of York (Law)

- King’s College, London (Law)

- University of Lancaster (Law & Student Success Team)

- University of Salford (School of Science, Engineering & Environment)

2024

- University of Cardiff (Law)

- University of Nottingham (Law)

- University of Portsmouth (Law)

- University of Manchester (Law)

I am currently working with colleagues at these institutions to gather feedback and the impact of this work. With cohorts of several hundred (and in one case over 1000) our work has already supported several thousand students nationwide. They are all explicitly acknowledging that their versions were inspired by the work of our student staff partnership.

In 2024 students asked, through course representatives on the Student Staff Partnership Group, whether we could create a Careers-focused Glossary. Jeff Anderson (our Careers Consultant) is working with student representatives and me to produce something suitable.

If you are interested in adopting and adapting the glossary for your students, please get in touch with Amanda as she is very happy to share the materials, advice and wants to gather more evidence of impact of this work.

![A man wearing a grey T-shirt and black pants against a yellow wall. He is sitting on the floor next to his laptop, with his hands making a film frame as he discusses a shot from a film playing on his laptop. The caption reads [Epic action film music].](https://sites.reading.ac.uk/t-and-l-exchange/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/2023/06/image-2-1024x576.jpg)

![A screenshot from an animated film. We see two hands, one on top of another, feeling the vibration of sound from a speaker. On the top-left is the following text that identifies the film and production details: Embrace (Animated Short), 2014, Debopriya Ghosh, National Institute of Design. The caption reads [Film Audio]: Muffled Music and static.](https://sites.reading.ac.uk/t-and-l-exchange/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/2023/06/image-1-1024x576.jpg)